Napoleon’s Military Carriage

Designed for optimum speed and utility, Napoleon’s military carriage carried the Emperor of the French all over the continent of Europe. Stripped of its wheels and lashed to a sleigh, it carried him back to Paris in the terrible retreat from Moscow. With the exiled Emperor it went to Elba; with him it returned. And it waited for him all one weekend near the village of Waterloo.

Later Sunday night, June 18, 1815 – while Napoleon was trying to escape from Waterloo – a pursuing troop overtook the carriage and captured it. Napoleon himself barely managed to escape on horseback, leaving behind his hat, sword, telescope, and – along with an immense treasure – a uniform in the lining of which were sewn unmounted diamonds worth a million gold francs.

Shortly thereafter, Napoleon’s military carriage was shipped to England and presented to the Prince Regent (later George IV) as a trophy of victory. It was exhibited on various occasions, and finally ended up in Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum – where, in 1925, it was totally destroyed by fire.

In its more than a century of public viewing, no one – as far as we have been able to discern – ever took the trouble to make drawings of it. But there are a number of written descriptions and two old musty photographs.

“Description of the Military Carriage of the late Emperor Napoleon taken at the Battle of Waterloo the night of June 18, 1815.

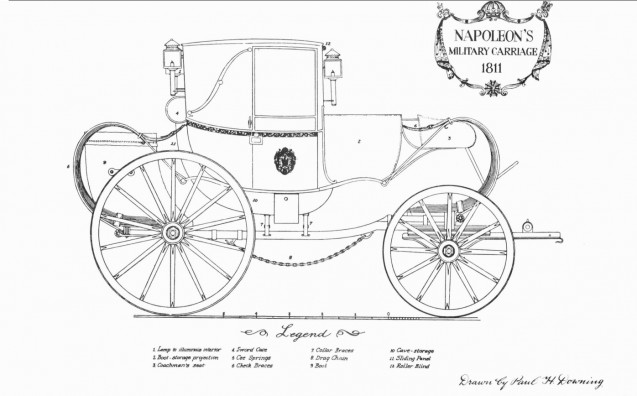

“And now let us look at this, the most remarkable carriage extant. The colour is a dark blue, with a handsome border ornamented in gold, and the Imperial arms are emblazoned on the pannels [sic] of the doors. It has a lamp at each corner of the roof, and there is one lamp fixed at the back, which can throw a strong light into the interior.

“In the front there is a great projection, the utility of which is very considerable. Beyond this projection, and nearer to the horses, is a seat for the coachman: this is ingeniously contrived, so as to prevent the driver from viewing the interior of the carriage; and… to afford those who are within, a clear sight of the horses, and of the surrounding country: there are two sabre cuts which were aimed at the coachman when the carriage was taken.

“The pannels [sic] of the carriage are bullet-proof: at the hinder part is a projecting sword case, and the pannel [sic] of the lower part of the back is so contrived, that it may be let down, and thereby facilitate the addition or removal of conveniences, without disturbing the traveller.

“The under carriage, which has sedan-neck iron cranes, is of prodigious strength: the springs are semi-circular, and each of them seems capable of bearing half a ton; the wheels, and more particularly the tires, are also of very great strength. The pole is contrived to act as a lever, by which the carriage is kept level in every kind of road. The under carriage and wheels are painted in vermillion, edged with the colour of the body, and heightened with gold.

“The doors of the carriage have locks and bolts; blinds behind the windows shut and open by means of a spring, and may be closed so as to form a barrier almost impenetrable.

“On the outside of the front window is a roller blind, made of strong painted canvass [sic]; when pulled down this will exclude rain or snow, and therefore secure the windows and blinds from being blocked up, as well as preventing the damp from penetrating.”

The Battle of Waterloo, 1815 (Anon.)

Official documents and contemporary accounts.

London, 1852.

Part Two – The Interior

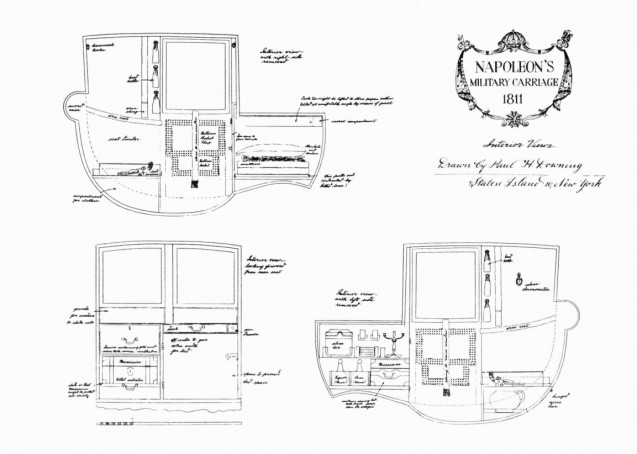

“The interior of this remarkable carriage deserves particular attention, for it is adapted to the various purposes of an office, a bed room, a dressing room, a kitchen and an eating room.

“There is a writing desk, opposite the seat in the rear, which may be drawn out so as to write while the carriage is proceeding; an ink stand, pens, etc. were found in it, and here was also found the Emperor’s personal atlas.

“There are also many smaller compartments, for maps and telescopes; on the ceiling a net hammock could be attached for carrying small travelling requisites.

“Beneath the coachman’s seat is a small box, about two feet and a half long… this contains a bedstead of polished steel, which could be fitted up within one or two minutes; the carriage contained mattresses and other requisites for bedding, of very extensive quality, all of them commodiously arranged. There are also articles for strict personal convenience, made of silver, fitted into the carriage.

“In front of the seat are compartments for every utensile [sic] of probably utilty: of some there are two sets, one of gold, the other of silver. Among the gold articles are a tea pot, coffee pot, sugar basin, candlesticks, wash-hand basin, plates for breakfast, etc. Each article is superbly embossed with the imperial arms, and engraved with his favourite “N”, and by the aid of a spirit lamp, any thing could be heated in the carriage.

“A small mahogany case, about ten inches square by eighteen long, contains the peculiar necessaire of the Ex-Emperor. It is somewhat in appearance like an English writing desk, having the imperial arms most beautifully engraved on the cover. It contains nearly one hundred articles, almost all… of solid gold.

“The liquor case, like the necessaire, is made of mahogany; it contains two bottles, one of them still has the rum which was found in it at the time, the other contains some extremely fine old Malaga wine.

“On either side of the carriage there is a pistol holster, in which were found pistols that had been manufactured at Versailles; and in a holster close to the seat, a double-barrelled pistol also was found. All the pistols were found loaded. On the right hand side there hung a silver chronometer, with a silver chain; it is of the most elaborate workmanship.

“All the articles which have been enumerated still remain with the carriage; but when it was taken there were a great number of diamonds, and a great treasure in money, etc. of immense value.”

The Battle of Waterloo, 1815, Anon.

Official documents and contemporary accounts

London, 1852

Technical note:

With the aid of these few fragments of description, two clouded old photographs, and the enormous fund of specialized knowledge held by Colonel Paul H. Downing, Consultant on Horse-drawn Vehicles and their Appointments, we have been able to diagram the marvellously engineered interior details of “the most remarkable carriage ever seen by man.”

The Fondation Napoléon gratefully thanks Jill Ryder, Mindy Groff, and The Carriage Museum of America for allowing us to reproduce this article from The Carriage Journal. Thanks are also due to the Archive of PanAm, for whom it was originally produced.