If, during your visit to the exhibition, you spied amongst the 280 works on display such a perfectly-formed vase, or a painting of such glorious colour, that you were compelled to search out further details in the exhibition's catalogue, you may well be disappointed. The items on display do not receive any further explanation and the actual catalogue section is rather restrained, occupying just 35 of the book's 270 pages. The catalogue's strength lies, on the other hand, in the collection of essays and discussions on the Anglo-French cultural dialogue that took place during a period of positive relations between the two countries.

Favourable conditions

Napoleon already knew England well, having spent some of his youth there in exile. The year 1855 was a key moment in the process of rapprochement between the two countries. Their joint participation in the Crimean War (1854-1856), in support of the Turkish forces fighting the Russians, played an extremely important role in this rapprochement, and this alliance led to reciprocal visits. Napoleon visited Windsor in April 1855, and Victoria, accompanied by Prince Albert and their children, spent time in Paris between 18 and 27 August.

The British Royal family stayed in the Palais de Saint-Cloud, which had been specially refitted for the visit.(1) In her essay, the art-historian Florence Austin Montenay explains how Napoleon III, in giving the Empress Eugenie's modern and feminine suite to Victoria, was treating the British Queen as a woman first and foremost. This attempt at “seduction” was important in the evolution of the relationship between the two sovereigns, from respectful formality to friendship.

A high-point of the trip was Victoria's visit to the tomb of Napoleon I at Les Invalides: in her diary, she recalled how she stood “on the arm of Napoleon III, before the coffin of our bitterest foe”, the tomb bathed in torchlight and the sound of “God save the Queen” ringing out. The catalogue makes clear the link between the diplomatic context and the cultural events that also took place: Emmanuel Starcky, Directeur des musées nationaux et du domaine des châteaux de Compiègne et Blérancourt and exhibition designer,(2) underlines just how desirous Napoleon III was of the Exposition Universelle in Paris and of a close-relationship between Britain and France.

The Exposition Universelle, 1855: the artistic context

Whilst the concept of the “exposition universelle” is both French and English in origin, the first actual exhibition was held in 1851 at Crystal Palace in London. The catalogue here is really the first to get to grips with the role of the universal exhibitions(3) in Anglo-French relations.(4) France, whose superiority in the aesthetic domain was generally recognised, was keen to encourage free trade, whilst Britain, technologically and industrially advanced, sought to promote the aesthetic quality of its products. In this highly competitive atmosphere, the two countries were often in conflict with each other, eclipsing other nations in many of the numerous and varied areas of production.

Perhaps the catalogue's key merit is its universal scope. Just as the exposition of 1855 covered all artistic forms, so does the catalogue. It also echoes the presentational structure employed at the Exposition Universelle, both in terms of divisions (“Industrial goods” were exhibited at the Palais de l'Industrie and “works of art” at the Palais des Beaux-arts) and in terms of form (“sculpture, engravings and fine stones”, for example). These divisions were deemed necessary due to the vast number of objects and items that were on display in 1855, with nearly 25,000 exhibitors, grouped by country. The scenography of the exhibition at Compiègne also tries to take into account this universal dimension and the modern-day visitor is given a little taste of the eclectic mix that was on offer to the five million-odd visitors in 1855.

Half a century of international painting

At the heart of the 1855 exposition universelle's diversity was the impressive retrospective of the contemporary art of the period: for the first time in history, fifty years of international painting was on offer to the public. The reputation of the English watercolour painters goes a long way to explain their success in 1855. Although less well-known today, these paintings on display were one of the revelations of the exhibition. The Anglophilia of the French public, keen admirers of Byron and Walter Scott, was a key factor in the exhibition's success, even if the new developments introduced by the Pre-Raphaelites(5) remained rather misunderstood.

Of the French contingent present in 1855, top-billing went to Ingres, Horace Vernet and Delacroix. All three were introduced to Victoria, but despite the presence of these big names, critics were disappointed. The history painting genre, considered by many to be the grand genre in the hierarchy of art-forms, appeared diminished, and the clash between classicism and romanticism felt tired. Faced with this apparent downturn in French painting, the English works of art appeared strong and exotic to the visitors. The French critics, their national pride injured by the public's interest in foreign production, tended to belittle the quality of the English school, criticising it for adopting an overly narrative style at the expense of the sublime. This plea in defence of the beau ideal was nevertheless tempered by contemporary debate regarding the realism in the works by Courbet. In the end, the painter Landseer was the sole Englishman to receive a medal of honour. Nevertheless, Napoleon III chose to also award a medal to Mulready.

An eclectic mix: from architecture to photography

As well as painting, other art-forms were also in the spotlight in 1855. The Universal Exhibition was also the largest collection of photographic works since the display of the first photographs by Daguerre in 1839. Even at this early stage, photography was being considered more and more an art-form. Despite English and French public recognition that photography could constitute ‘art', the organisers nevertheless preferred to display the works in the Palais d'Industrie rather than the Palais des Beaux-Arts. These artistic qualities, appreciated as such by the general public, were clearly evident in the photographs taken of the Crimean War, the first prints of which were commissioned by Napoleon III and Victoria.

English sculpture and decorative arts, however, were less well received. The French furniture industry demonstrated a clear taste for objects in the 18th century-style and in a variety of different types of wood (including the thuja from Algeria). The Fourdinois and Baredienne “maisons” went on to win two grandes médailles d'honneur at the exposition. However, 1855 was not a great year for the ceramic industry and was characterised in particular by the rivalry between the French Sèvres manufactory and the English Minton manufactory, a rivalry which was underpinned by serious economic issues. And whilst the Lyonnais silk manufacturers were able to offer a product of better quality than that of their English counterparts, the latter benefited greatly from their country's strength in industry and technology, and from the wealth of imports that was made possible by the enormity of the British Empire.

At this time, French architects were fascinated by Antiquity and the Middle Ages; their English counterparts, on the other hand, were far more interested in the idea of modernity, and were greatly disappointed to see that the Exposition Universelle did not have a place for Baron Haussmann's recent innovations in Parisian urban development. In his essay, Philippe Greusset, Maître-assistant at the Ecole nationale supérieure d'architecture de Paris-Malaquais, discusses the English influence and the role that it played in the major redevelopment works that went on in France.

Influence, exchange and friendship

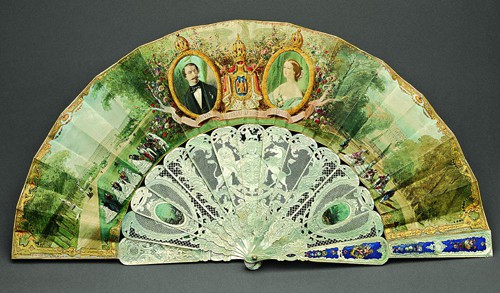

The exposition universelle was also the opportunity for the sovereigns to exchange gifts. On display at Compiègne is a beautiful fan that was offered by Napoleon III to Victoria. “La Rixe” by Ernest Meissonier was also given, this time to Prince Albert, by the French emperor, who paid full price for the artwork.

Seen as part of the European cultural season (1 July – 31 December 2008), this catalogue continues in the spirit of cultural exchange. The reader can also take advantage of the substantial and well-considered bibliography and the practical index, ordered by names, places and themes.

Place and year of publication:

“Napoléon III et la reine Victoria, une visite à l'exposition universelle de 1855”, catalogue de l'exposition du Château de Compiègne, 4 octobre 2008-19 janvier 2009, Paris, 2008.

Publisher:

Réunion des Musées Nationaux

Number of pages:

271

(Tr. & ed. H.D.W.)