The Spanish ownership

Although this area had in fact belonged to France during the first half of the 18th century, in the treaties following the Seven Years War (1755-62) where France had been on the losing side, it had been ceded to Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). This Spanish territory was to be further enlarged twenty years later in the aftermath of the collapse of the First Coalition against Revolutionary France in 1795, when England ceded to Spain both East and West Florida, leaving Spain not only in possession of the central part of the North American continent but also master of its entire southern seaboard.

However, unlike in Florida and Mexico which became thoroughly Spanish, Spain never managed to leave its mark on Louisiana. That territory was far too large, and Spain never invested enough either in terms of money or manpower to make it a viable colony. In fact this period of Spanish hegemony coincided with a decline in Spanish fortunes and submission to France. As for France’s claims on the territory, significant numbers of Creoles, whose language was a sort of French, had remained and they were strongly attached to France and resistant to their new Hispanic landlords.

French attempts at repossession

In the period immediately following the Seven Years War, France yearned for her ‘American empire’, looking back with nostalgia to days when French explorers were planting the tricolor throughout the New World. But the path to the re-possession of Louisiana was not an easy one. Not only was France opposed by her traditional enemy, Britain, she also faced valiant resistance on the part of Spain, notably through the work of chief minister Godoy. Furthermore the, at best ambiguous and at worst hostile, eastern United States were also opposed, firstly for strategic reasons – the young union did not want a strong ‘old world’ colony next door (as the federalist Treasury Secretary Oliver Wolcott Jr. during the Directory period noted, the French would be ‘the worst and most dangerous of neighbours we could have […] like ants and weasels in our barns and granaries’), and secondly (and more importantly) because of (very discreet) expansionist desires of its own. The Mississippi had always been an important trade artery and draconian Spanish attempts to regulate commerce on the river had inflamed the American traders and farmers who depended on the outlet for the transport their products.

French victory over the First Coalition and the (first) Treaty of San Ildefonso, 1796

The first real chance France had of reclaiming Louisiana was in 1795, when she emerged victorious from the collapse of the First Coalition. Previously French policy had been to lull American fears regarding French designs on Louisiana by reiterating that French interest in Louisiana was simply to keep the British out. In the confidence generated by the success against the First Coalition, this pretence was set aside and the French made open attempts to reacquire the colony simply for colonial reasons. Delacroix, minister of Foreign Relations, demanded the region from Spain; and not only as an imperial possession but also as an instrument for exerting influence over the American Government. But despite the generally friendly terms of this the first Treaty of San Ildefonso, France was faced with the determined opposition of Godoy on the subject of the American territory. In the end, Spain was only willing to cede the Spanish part of Santo Domingo, which faute de mieux France accepted. In face of this setback, Talleyrand further stoked French imperialist fires in July 1797 in a paper which he read to the Institut, speaking of the benefits of colonies, citing Egypt, Lousiana and West Africa – simultaneously noting that repossession of the colony would help stifle American expansionism and act as a barrier between the United States and Spain. In 1798, negotiations for ‘Louisiana’ under Talleyrand opened again, only to be hampered by a series of unfortunate developments, namely, the outbreak of the Quasi-War between France and America, and the ‘XYZ’ scandal (news broke concerning how Talleyrand’s agents’ had demanded kickbacks from American diplomats), which lead to Talleyrand’s resignation and the shelving of the project.

The (second) Treaty of San Ildefonso, 1800

However, on his becoming First Consul, Bonaparte made it one of his first actions of foreign policy to relaunch the 40-year old Louisiana repossession issue. After the recent failure of the Egyptian expedition, the First Consul and especially Talleyrand (Foreign Minister for the Brumairian régime), looked with greater urgency at the possibility of establishing a French Empire, this time in the West. After the re-opening of bi-lateral Franco-Spanish negociations in July 1800, led by Talleyrand and Spain’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Mariano Luis de Urquijo, it appeared that Spain was willing to cede the territory in return for land in Italy. Bonaparte attempted to speed up the talks by sending Berthier to Spain as special envoy. The latter’s instructions were to demand Louisiana, the Floridas and ten warships in return for territory of indefinite size in Italy for the Duke of Parma. Despite a smooth parley, Carlos IV, king of Spain, refused to cede the Floridas and only offered six warships. And so, the day after the Convention of Mortefontaine sealed Franco-American goodwill and the end of the Quasi-War on 30 September, 1800, Berthier signed the secret convention of San Ildefonso, whereby the Spanish king would cede Louisiana to France and also give six warships. In return, Bonaparte would provide a kingdom in Italy for the duke of Parma. The convention remained secret so as not to goad America and Britain into invading the territory before French troops could be sent to defend it.

But attached to clauses in this second Ildefonso treaty were provisos. The First Consul had agreed not to take possession of the territory until a) he had delivered the Italian kingdom to the duke of Parma and b) the latter’s sovereignty had generally been recognised. Furthermore, the war in Europe was still raging, and Tuscany (the land Bonaparte intended to give to the Spanish) was not yet fully in his power to dispose of it as he wanted. He had to wait until peace was finally obtained via the Treaty of Lunéville (9 February, 1801). In that treaty, by which the First Consul got possession of Tuscany, a secret clause provided the displaced Habsburg Grand Duke with land in Germany in return for the cession of his Italian fief. The Italian state was renamed the Kingdom of Etruria, and given not to the duke of Parma (whom Bonaparte disliked) but to the duke’s son, Luis. The Convention of Aranjuez (21 March, 1801) confirmed and altered accordingly the previous year’s Ildefonso treaty, adding to the exchange, the island of Elba (for the French), giving Luis Piombino (seized from Naples) in return.

The view from the other side of the Atlantic

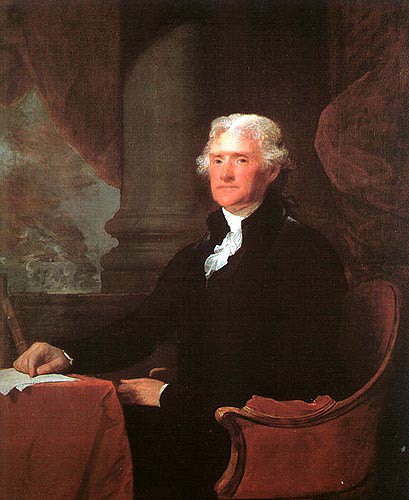

On learning of the secret cession of Louisiana from Rufus King, US federalist minister in London, in the autumn of 1801, the American President, Thomas Jefferson considered it unwise, ominous and as undoing the peace settlement of Mortefontaine. And after a barbed conversation with Louis André Pichon, the newly arrived French Chargé d’affaires in Washington, Secretary of State James Madison, noted aggressively that ‘if the transfer took place, France would collide with the United States.’ In doubt as to whether France had received Louisiana, Jefferson gave instructions to the francophile New York politician, Robert R. Livingston, recently appointed Minister to France, to ascertain the truth of the matter. If it had not been ceded, Livingston was to express America’s opposition to the exchange. If it had been, Jefferson charged the Minister to France to offer to purchase the territory. Talleyrand’s reply to Livingston’s offer to buy Louisiana in exchange for French debts to the US, (Recorded in Livingston’s correspondence with Madison, American State Papers, Foreign Relations, II, 512.) was ‘None but spendthrifts satisfy their debts by selling their land. But it is not ours to give’. (Cited in DeConde, A., This affair of Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976.)

On learning of the secret cession of Louisiana from Rufus King, US federalist minister in London, in the autumn of 1801, the American President, Thomas Jefferson considered it unwise, ominous and as undoing the peace settlement of Mortefontaine. And after a barbed conversation with Louis André Pichon, the newly arrived French Chargé d’affaires in Washington, Secretary of State James Madison, noted aggressively that ‘if the transfer took place, France would collide with the United States.’ In doubt as to whether France had received Louisiana, Jefferson gave instructions to the francophile New York politician, Robert R. Livingston, recently appointed Minister to France, to ascertain the truth of the matter. If it had not been ceded, Livingston was to express America’s opposition to the exchange. If it had been, Jefferson charged the Minister to France to offer to purchase the territory. Talleyrand’s reply to Livingston’s offer to buy Louisiana in exchange for French debts to the US, (Recorded in Livingston’s correspondence with Madison, American State Papers, Foreign Relations, II, 512.) was ‘None but spendthrifts satisfy their debts by selling their land. But it is not ours to give’. (Cited in DeConde, A., This affair of Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976.)

Roughly summed up, the US position was that they did not wish to appear voraciously interested in what was in effect foreign land, but they also did not want the land to fall into non-American (or at any rate non-Spanish) hands. And here Washington political opinion was in tune with the provinces. As many pamphlets of the time show well, the settlers would have fought hard rather than see the fertile prairies to the west fall into French hands. An important exhortation published in Philadelphia 1802 ‘An Address to the Government of the United States on the Cession of Louisiana to the French’ shows the mood. It began by quoting a confident French Conseiller d’Etat who gaily informed his readers of the boundless fertile prairies to be found in Louisiana, and the feeble nature of possible American opposition – they were (that Councillor said) a ‘nation of pedlars and shopkeepers’ that could be crushed by an alliance of French and Indians. The American writer then continued ‘France is to be dreaded only […] on the Mississippi. The Government must take Louisiana now before it passes into her hands’. Jefferson’s position can be seen from a private letter to Livingston dated 18 April, 1802, ‘There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans…’.

And yet, it is clear that militarily speaking the young United States were, as Thierry Lentz has put it, ‘dwarves’. They could not have effectively repulsed any French designs upon the ex-colony – although a guerrilla war could certainly have been envisaged. So the threat of French re-acquisition pushed the States closer to Britain. However, such a posture was likewise fraught with difficulty, since Jefferson rightly feared that any increased British presence would result in the young United States being surrounded on all sides by British territory, namely, by Canada, Louisiana and the Floridas. To complicate matters still further, Britain was now fighting shy of getting involved in the Louisiana question. In April, 1802, Lord Hawkesbury declared to the House of Commons, ‘that it was sound policy to place the French in such a manner with respect to America as would keep the latter in a perpetual state of jealousy with respect to the former, and of consequence unite them in closer bonds of amity with Great Britain’. (Annual Register for 1802, London, 1803, p. 264.)

Santo Domingo, the key to French repossession of Louisiana

But Bonaparte could not however push for immediate re-possession of Louisiana. France was still as war with Britain and was to remain so until the 27 March, 1802, and the signing of the Peace of Amiens. Furthermore, Santo Domingo (one of the larger islands in the West Indies relatively close to New Orleans, today’s Haiti and the Dominican Republic), the staging point from which the repossession was to take place, was in ferment with slaves in revolt and Toussaint-Louverture in power. So, the first step on the road to a French return to Louisiana would have to be the re-establishment of French control on Santo Domingo.

In 1800, the slaves in the French part of Santo Domingo had revolted. And Toussaint-Louverture, who had emerged by sheer force of character and will as leader, had led the island into quasi-secession from the mother country. Having brought order to his part of the island, the former slave then invaded the Spanish-held side with 20,000 troops. In May 1801, he made a constitution for the island and declared himself governor for life, with powers to appoint his successor. Though he was right in the middle of the preliminaries for the Peace of Amiens, Bonaparte nevertheless took the Santo Domingo problem very seriously, publicly flattering Toussaint and asking him to alter parts of his constitution to bring the country into line with France, whilst privately (notably to Talleyrand, letter of 30 October, 1801) noting that ‘it was for the benefit of civilisation that this new Algiers in American waters be destroyed’ and two weeks later (letter to Talleyrand of 13 November, 1801) that he had decided to ‘destroy the black government on Santo Domingo’.

As a result, Bonaparte sent General Leclerc, his brother-in-law, with 20,000 men, thirty-two ships of the line and thirty-one frigates to bring the ex-colony back under control. They set sail on 14 December, arriving on 29 January, 1802. So large was the French force sent that Britain saw fit to send a fleet too, to keep an eye on things. As Lord Grenville was to remark in the House of Lords (13th May, 1802), Britain ‘had had to send to the West Indies in time of peace a fleet double as large as that kept there during the late war’.

Leclerc finally forced Toussaint and his forces to surrender on 8 May, 1802 – Toussaint was not however imprisoned but, since he had demanded that his official rank be respected, simply confined on parole. Subsequently, with the onset of the unhealthy season on the island (forces were reduced from 20,000 to 12,000 men in active service) Leclerc seized Toussaint and had him sent back to France, along with other generals (as per Bonaparte’s orders of 16 March, 1802). That deportation together with news of Richpance’s re-institution of slavery on Guadaloupe led to another uprising on Santo Domingo in the August of 1802. This, a revolt by a desperate enemy, combined with mutinies and desertions within his own forces, left the French commander in very difficult circumstances. Fighting a rearguard action, whilst retreating from the interior to the coast and forced to enlist local (and therefore possibly fickle) troops, Leclerc was to succumb to yellow fever on 2 November, 1802.

Meanwhile back in France…

Just as Santo Domingo was beginning to fall into anarchy, Napoleon (unaware of the crisis) added the key-stone to his Santo Domingo/Louisiana policy, appointing Claude Victor, Duc de Bellune, as Governor of Louisiana (April, 1802). Shortly afterwards, he gave notice to Admiral Decrès (circa 4 June, 1802) that ‘it is our intention to take Louisiana as soon as possible; and that the expedition take place in the greatest secrecy; it should appear to be heading for Santo Domingo […] you should present to me a project for the organisation of this colony, both military and administrative…’ (Letter to Decrès, circa 4 June, 1802). The flotilla, of twelve vessels and more than three thousand men (at a cost of 3 million franc) was to gather in Holland, where it went by the code name ‘l’Expedition Flessingue’ (the Flushing expedition). However, ice kept the force in the Dutch port of Helvoët Sluys over the whole winter, as Decrès desperately tried to bring together the men and equipment required. During the ice blockage, on 7 January, 1803, the First Consul received news of Leclerc’s death and the losses suffered. It was at this time (12 January, 1803) that he uttered the famous words recorded by Roederer, ‘Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies’. (Oeuvres du Comte P. L. Roederer, ed. A. M. Roederer, Paris: Firmin, vol. 3, p. 461.) In the meantime, Bonaparte had been forced to send Rochambeau to help the suffering French forces in Santo Domingo (15,000 men initially, and 15,000 later), stretching Decrès’s resources to the limit. And so in the spring of 1803, just when the weather was finally clement enough for the expedition to set out, the international political situation had deteriorated to such an extent that war with Britain was imminent. So much so that Britain feared that the destination of the ‘Flushing expedition’ could be changed at the last moment to become the British Isles. By mid-March, Bonaparte learned from dispatches from Rochambeau that 50,000 men had died to date on Santo Domingo. An article in the London Times, 7 April, 1803, noted belligerent trans-Atlantic noises on the Louisiana question. Whoever possessed Louisiana, it noted that ‘the [American] government and people seem to be aware that a decisive blow must be struck before the arrival of the expedition now awaiting in the ports of Holland.

Meanwhile back in Spain…

As for the official papers of transfer of the Spanish colony, Godoy and the Spanish continued to drag their heels throughout the summer of 1802. They noted that the French were still effectively in control of Etruria, and neither Britain nor Austria had officially recognised Etruria, as the Convention of Aranjuez had stipulated. Bonaparte reacted angrily, asking his ambassador in Spain, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr ‘to tell the Queen and the Prince of Peace that if they continue this system [of delay], it will end with a thunderbolt’. (Cited in DeConde, A., This affair of Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976.) Appearing to buckle before the First Consul’s threats, the Spanish rulers insisted in addition that Bonaparte sign a clause guaranteeing ‘not to sell or alienate in any manner the property and usufruct of this Province’. Through Gouvion Saint-Cyr, the First Consul agreed to the terms and, finally more than two years after the initial agreement of transfer, on 15 October, 1802, Carlos IV signed the documents formally ordering his colonial officials to cede Louisiana to France.

The moment of truth

So Bonaparte had the deeds for Louisiana. All he had to do was take it. But as we have seen, the spring of 1803 was precisely the wrong moment. Santo Domingo was in torment. America was exceedingly hostile to French possession of Louisiana. As Pichon had noted to Bonaparte in a dispatch dated March 1803, French colonies in America could not exist for long without American friendship ‘we are dependent upon them [the Americans] in time of peace; at their mercy in the first war with England.’ Any movement against the will of the Americans would push the US close to Britain. War was about to break with Great Britain. Thiers cites Napoleon’s words at this juncture: “‘I shall not keep’ he said to one of his ministers, ‘a possession which will not be safe in our hands, which will perhaps be the cause of a clash with the Americans or perhaps make them cold towards me. On the contrary, I shall use it to bind them to me, to cause them to break with the British, and I shall create enemies against the latter who shall one day avenge us. My mind is made up. I shall give Louisiana to the United States. But since they do not have any territory to give us in return, I shall ask them for some money so as to fund the extra armaments which I preparing to launch against Great Britain.” (Thiers, Histoire du Consulat, Livre XVI, March 1803.) However, as Alexander DeConde interestingly points out, if money had been the only interest, Bonaparte could (and should) have sold Louisiana back to the Spanish – they would even have given him more money. But the tactical advantage of depriving Great Britain and ensuring US goodwill overruled the agreement to return the territory to Spain.

So almost as if changing his mind, the First Consul abandoned all desires for empire. According to Barbé-Marbois in his History of Louisiana, the First Consul summoned Talleyrand on 11 April, addressing him saying ‘Irresolution and deliberation are no longer in season. I renounce Louisiana. I have proved the importance I attach to this province, since my first diplomatic act with Spain had the object of recovering it. I renounce it with the greatest regret: to attempt obstinately to retain it would be folly. I direct you to negotiate the affair.’ (Barbé-Marbois, François, The history of Louisiana, Philadelphia: Carey & Lea, 1830, pp. 298-299.) Later that day, Talleyrand invited Livingston to meet him to barter. The American agent offered the French minister 20 million francs, which the latter rejected out of hand as too low, asking Livingston to think again. Shortly afterwards, the First Consul summoned his brothers Joseph and Lucien to the Tuileries to discuss the matter. Here, according to Lucien in his memoirs, Napoleon received them whilst in the bath. The brothers strongly objected to the sale, but Napoleon took no notice of them, jeering at them, saying that he cared nothing for their opposition, and on purpose soaked Joseph with bath water. (Th. Iung: Lucien Bonaparte et ses mémoires 1775-1840, Paris: G. Charpentier éditeur, 1882, 3 volumes, see vol. 2, pp. 147-155.) Barbé-Marbois, treasury minister, was called to conduct the French bargaining. Bonaparte made it known that he wanted 50 million francs. Barbé-Marbois started off at 100 million. The haggling which Livingston had initially suggested had finally begun. James Monroe joined the negotiations on 14 April, and a price was agreed. The treaty was signed on 30 April, 1803, and the United States received that huge territory for the paltry sum of 15 million dollars – 11.25 million (60 million francs) went directly into the Consular state’s treasury. The rest was to be paid by the US Government to indemnify American citizens who had lost vessels or cargoes as a result of the hostilities between Britain and France. Not only did the sale fill the French war chest, it was also portrayed, with masterly spin, as a graceful act towards the United States and a blow to England. Pierre-Clement de Laussat, the colonial prefect, actually already in Louisiana preparing for the French occupation received Napoleon’s note that the colony had been sold to the US as he put it, ‘like a bolt out of the blue’. As per the treaty, he formally had to receive the land from Spain so he could then pass it on to the United States.

Postscript

Spain formally protested to both Jefferson and Bonaparte that the transaction was not legal, as the First Consul had formally agreed to return the land to Spain, should he not keep it himself. The Spanish minister for Foreign Affairs, Pedro de Cevallos denounced the sale, saying that France had broken its word – furthermore, French troops were still occupying Etruria. But for the First Consul, Spain was merely a client state, not to be worried about. And Spain’s weak acceptance of the status quo after the sale merely served to encourage him in his poor opinion of Carlos and Godoy. In the autumn of 1803, Jefferson, Madison and Pichon all moved fast to enable the payment for, and occupation of, Louisiana, which had been voted through Congress on 3 November, 1803. And the celebrations which took place around the taking of possession served Jefferson well, leading him to a landslide re-election in 1804.

Bibliography

– DeConde, Alexander, This affair of Louisiana, Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1976

– Lentz, Th., “La vente de la Louisiane : une bonne affaire commerciale” in Napoléon Ier : le magazine du Consulat et de l’Empire, No 19, (03/2003), pp. 16-19

– Martin, J., La révolte des Antilles, 1800-1804, in Napoléon Ier : le magazine du Consulat et de l’Empire, No 19, (03/2003), pp. 12-15

– Rose, John Holland, The life of Napoleon, London: G. Bell and sons, 1913.