Among the eminent persons of the nineteenth century, Bonaparte is far the best known and the most powerful; and owes his predominance to the fidelity with which he expresses the tone of thought and belief, the aims of the masses of active and cultivated men. (1) It is Swedenborg’s theory that every organ is made up of homogeneous particles; or as it is sometimes expressed, every whole is made of similars; that is, the lungs are composed of infinitely small lungs; the liver, of infinitely small livers; the kidney, of little kidneys, etc. (2) Following this analogy, if any man is found to carry with him the power and affections of vast numbers, if Napoleon is France, if Napoleon is Europe, it is because the people whom he sways are little Napoleons.

In our society there is a standing antagonism between the conservative and the democratic classes; (3) between those who have made their fortunes, and the young and the poor who have fortunes to make; between the interests of dead labor,- that is, the labor of hands long ago still in the grave, which labor is now entombed in money stocks, (4) or in land and buildings owned by idle capitalists,- and the interests of living labor, which seeks to possess itself of land and buildings and money stocks. The first class is timid, selfish, illiberal, hating innovation, and continually losing numbers by death. The second class is selfish also, encroaching, bold, self-relying, always outnumbering the other and recruiting its numbers every hour by births. It desires to keep open every avenue to the competition of all, and to multiply avenues: the class of business men in America, in England, in France and throughout Europe; the class of industry and skill. Napoleon is its representative. The instinct of active, brave, able men, throughout the middle class everywhere, has pointed out Napoleon as the incarnate Democrat. (5) He had their virtues and their vices; above all, he had their spirit or aim. That tendency is material, pointing at a sensual success and employing the richest and most various means to that end; conversant with mechanical powers, highly intellectual, widely and accurately learned and skilful, but subordinating all intellectual and spiritual forces into means to a material success. (6) To be the rich man, is the end. “God has granted,” says the Koran, “to every people a prophet in its own tongue.” Paris and London and New York, the spirit of commerce, of money and material power, were also to have their prophet; and Bonaparte was qualified and sent.

Every one of the million readers of anecdotes or memoirs or lives of Napoleon, delights in the page, because he studies in it his own history. (7) Napoleon is thoroughly modern, and, at the highest point of his fortunes, has the very spirit of the newspapers. He is no saint,- to use his own word, “no capuchin,” (8)and he is no hero, in the high sense. The man in the street finds in him the qualities and powers of other men in the street. He finds him, like himself, by birth a citizen, who, by very intelligible merits, arrived at such a commanding position that he could indulge all those tastes which the common man possesses but is obliged to conceal and deny: good society, good books, fast travelling, dress, dinners, servants without number, personal weight, the execution of his ideas, the standing in the attitude of a benefactor to all persons about him, the refined enjoyments of pictures, statues, music, palaces and conventional honors,- precisely what is agreeable to the heart of every man in the nineteenth century, this powerful man possessed. (9)

It is true that a man of Napoleon’s truth of adaptation to the mind of the masses around him, becomes not merely representative but actually a monopolizer and usurper of other minds. Thus Mirabeau plagiarized every good thought, every good word that was spoken in France. Dumont relates (10) that he sat in the gallery of the Convention and heard Mirabeau make a speech. It struck Dumont that he could fit it with a peroration, which he wrote in pencil immediately, and showed it to Lord Elgin, who sat by him. Lord Elgin approved it, and Dumont, in the evening, showed it to Mirabeau. Mirabeau read it, pronounced it admirable, and declared he would incorporate it into his harangue tomorrow, to the Assembly. “It is impossible,” said Dumont,“ as, unfortunately, I have shown it to Lord Elgin.” “If you have shown it to Lord Elgin and to fifty persons beside, I shall still speak it to-morrow”: and he did speak it, with much effect, at the next day’s session. (11) For Mirabeau, with his overpowering personality, felt that these things which his presence inspired were as much his own as if he had said them, and that his adoption of them gave them their weight. Much more absolute and centralizing was the successor to Mirabeau’s popularity and to much more than his predominance in France. Indeed, a man of Napoleon’s stamp almost ceases to have a private speech and opinion. (12) He is so largely receptive, and is so placed, that he comes to be a bureau for all the intelligence, wit and power of the age and country. He gains the battle; he makes the code; (13) he makes the system of weights and measures; (14) he levels the Alps; (15) he builds the road. (16) All distinguished engineers, savans, statists, report to him: so likewise do all good heads in every kind: he adopts the best measures, sets his stamp on them, and not these alone, but on every happy and memorable expression. Every sentence spoken by Napoleon and every line of his writing, deserves reading, as it is the sense of France. (17)

Bonaparte was the idol of common men because he had in transcendent degree the qualities and powers of common men. (18) There is a certain satisfaction in coming down to the lowest ground of politics, for we get rid of cant and hypocrisy. Bonaparte wrought, in common with that great class here presented, for power and wealth,- but Bonaparte, specially, without any scruple as to the means. All the sentiments which embarrass men’s pursuit of these objects, he set aside. The sentiments were for women and children. Fontanes, in 1804, expressed Napoleon’s own sense, when in behalf of the Senate he addressed him,- “Sire, the desire of perfection is the worst disease that ever afflicted the human mind.” (19) The advocates of liberty and of progress are “ideologists”;- a word of contempt often in his mouth; (20) “Necker is an ideologist”: (21) “Lafayette is an ideologist.” (22)

An Italian proverb, too well known, declares that “if you would succeed, you must not be too good.” It is an advantage, within certain limits, to have renounced the dominion of the sentiments of piety, gratitude and generosity; (23) since what was an impassable bar to us, and still is to others, becomes a convenient weapon for our purposes; just as the river which was a formidable barrier, winter transforms into the smoothest of roads.

Napoleon renounced, once for all, sentiments and affections, and would help himself with his hands and his head. (24) With him is no miracle and no magic. He is a worker in brass, in iron, in wood, in earth, in roads, in buildings, in money and in troops, and a very consistent and wise master workman. He is never weak and literary, (25) but acts with the solidity and the precision of natural agents. He has not lost his native sense and sympathy with things. (26) Men give way before such a man, as before natural events. To be sure there are men enough who are immersed in things, as farmers, smiths, sailors and mechanics generally; and we know how real and solid such men appear in the presence of scholars and grammarians: but these men ordinarily lack the power of arrangement, and are like hands without a head. (27) But Bonaparte superadded to this mineral and animal force, insight and generalization, so that men saw in him combined the natural and the intellectual power, as if the sea and land had taken flesh and begun to cipher. Therefore the land and sea seem to presuppose him. He came unto his own and they received him. This ciphering operative (28) knows what he is working with and what is the product. He knew the properties of gold and iron, of wheels and ships, of troops and diplomatists, and required that each should do after its kind.

The art of war was the game in which he exerted his arithmetic. It consisted, according to him, in having always more forces than the enemy, on the point where the enemy is attacked, or where he attacks: (29) and his whole talent is strained by endless manoeuvre and evolution, (30) to march always on the enemy at an angle, (31) and destroy his forces in detail. (32) It is obvious that a very small force, skilfully and rapidly manoeuvring so as always to bring two men against one at the point of engagement, will be an overmatch for a much larger body of men.

The times, his constitution and his early circumstances combined to develop this pattern democrat. He had the virtues of his class and the conditions for their activity. That common-sense which no sooner respects any end than it finds the means to effect it; the delight in the use of means; in the choice, simplification and combining of means; the directness and thoroughness of his work; the prudence with which all was seen and the energy with which all was done, make him the natural organ and head of what I may almost call, from its extent, the modern party.

Nature must have far the greatest share in every success, (33) and so in his. Such a man was wanted, and such a man was born; (34) a man of stone and iron, capable of sitting on horseback sixteen or seventeen hours, of going many days together without rest or food except by snatches, (35) and with the speed and spring of a tiger in action; a man not embarrassed by any scruples; compact, instant, selfish, prudent, and of a perception which did not suffer itself to be baulked or misled by any pretences of others, or any superstition or any heat or haste of his own. “My hand of iron,” he said, “was not at the extremity of my arm, it was immediately connected with my head.” (36) He respected the power of nature and fortune, and ascribed to it his superiority, instead of valuing himself, like inferior men, (37) on his opinionativeness, and waging war with nature. His favorite rhetoric lay in allusion to his star; (38) and he pleased himself, as well as the people, when he styled himself the “Child of Destiny.” (39) “They charge me,” he said, “with the commission of great crimes: (40) men of my stamp do not commit crimes. Nothing has been more simple than my elevation, ‘tis in vain to ascribe it to intrigue or crime; it was owing to the peculiarity of the times and to my reputation of having fought well against the enemies of my country. I have always marched with the opinion of great masses and with events. (41) Of what use then would crimes be to me?” (42) Again he said, speaking of his son, “My son can not replace me; I could not replace myself. I am the creature of circumstances.” (43)

He had a directness of action never before combined with so much comprehension. He is a realist, (44) terrific to all talkers and confused truth-obscuring persons. He sees where the matter hinges, throws himself on the precise point of resistance, and slights all other considerations. He is strong in the right manner, namely by insight. He never blundered into victory, but won his battles in his head before he won them on the field. (45) His principal means are in himself. (46) He asks counsel of no other. In 1796 he writes to the Directory: “I have conducted the campaign without consulting anyone. I should have done no good if I had been under the necessity of conforming to the notions of another person. I have gained some advantages over superior forces and when totally destitute of every thing, because, in the persuasion that your confidence was reposed in me, my actions were as prompt as my thoughts.” (47)

History is full, down to this day, of the imbecility of kings and governors. (48) They are a class of persons much to be pitied, for they know not what they should do. The weavers strike for bread, and the king and his ministers, knowing not what to do, meet them with bayonets. But Napoleon understood his business. Here was a man who in each moment and emergency knew what to do next. (49) It is an immense comfort and refreshment to the spirits, not only of kings, but of citizens. Few men have any next; (50) they live from hand to mouth, without plan, and are ever at the end of their line, and after each action wait for an impulse from abroad. Napoleon had been the first man of the world, if his ends had been purely public. (51) As he is, he inspires confidence and vigor by the extraordinary unity of his action. He is firm, sure, self-denying, self-postponing, sacrificing everything,- money, troops, generals, and his own safety also, to his aim; not misled, like common adventurers, by the splendor of his own means. “Incidents ought not to govern policy,” he said, “but policy, incidents.” (52) “To be hurried away by every event is to have no political system at all.” (53) His victories were only so many doors, and he never for a moment lost sight of his way onward, in the dazzle and uproar of the present circumstance. He knew what to do, and he flew to his mark. He would shorten a straight line (54) to come at his object. Horrible anecdotes may no doubt be collected from his history, of the price at which he bought his successes; but he must not therefore be set down as cruel, but only as one who knew no impediment to his will; (55) not bloodthirsty, not cruel, (56) – but woe to what thing or person stood in his way! Not bloodthirsty, but not sparing of blood,- and pitiless. (57) He saw only the object: the obstacle must give way. (58) “Sire, General Clarke can not combine with General Junot, for the dreadful fire of the Austrian battery.”- “Let him carry the battery.”- “Sire, every regiment that approaches the heavy artillery is sacrificed: Sire, what orders?”- “Forward, forward!” (59) Seruzier, a colonel of artillery, gives, in his “Military Memoirs,” the following sketch of a scene after the battle of Austerlitz.- “At the moment in which the Russian army was making its retreat, painfully, but in good order, on the ice of the lake, the Emperor Napoleon came riding at full speed toward the artillery. ‘You are losing time,’ he cried; ‘fire upon those masses; they must be engulfed: fire upon the ice!’ The order remained unexecuted for ten minutes. In vain several officers and myself were placed on the slope of a hill to produce the effect: their balls and mine rolled upon the ice without breaking it up. Seeing that, I tried a simple method of elevating light howitzers. The almost perpendicular fall of the heavy projectiles produced the desired effect. My method was immediately followed by the adjoining batteries, and in less than no time we buried” some “thousands of Russians and Austrians under the waters of the lake.” (60)

In the plenitude of his resources, every obstacle seemed to vanish. “There shall be no Alps,” (61) he said; and he built his perfect roads, climbing by graded galleries their steepest precipices, until Italy was as open to Paris as any town in France. (62) He laid his bones to, and wrought for his crown. Having decided what was to be done, he did that with might and main. He put out all his strength. He risked every thing and spared nothing, (63) neither ammunition, nor money, nor troops, nor generals, nor himself.

We like to see every thing do its office after its kind, whether it be a milch-cow or a rattlesnake; (64) and if fighting be the best mode of adjusting national differences, (as large majorities of men seem to agree,) certainly Bonaparte was right in making it thorough. The grand principle of war, he said, was that an army ought always to be ready, by day and by night and at all hours, to make all the resistance it is capable of making. (65) He never economized his ammunition, but, on a hostile position, rained a torrent of iron,- shells, balls, grapeshot,-to annihilate all defence. On any point of resistance he concentrated squadron on squadron in overwhelming numbers until it was swept out of existence. (66) To a regiment of horse-chasseurs at Lobenstein, two days before the battle of Jena, Napoleon said, “My lads, you must not fear death; when soldiers brave death, they drive him into the enemy’s ranks.” (67) In the fury of assault, he no more spared himself. He went to the edge of his possibility. It is plain that in Italy he did what he could, and all that he could. He came, several times, within an inch of ruin; and his own person was all but lost. (68) He was flung into the marsh at Arcola. The Austrians were between him and his troops, in the melee, and he was brought off with desperate efforts. (69) At Lonato, and at other places, he was on the point of being taken prisoner. (70) He fought sixty battles. (71) He had never enough. Each victory was a new weapon. “My power would fall, were I not to support it by new achievements. Conquest has made me what I am, and conquest must maintain me.” (72) He felt, with every wise man, that as much life is needed for conservation as for creation. We are always in peril, always in a bad plight, just on the edge of destruction and only to be saved by invention and courage.

This vigor was guarded and tempered by the coldest prudence and punctuality. (73) A thunderbolt in the attack, (74) he was found invulnerable in his entrenchments. His very attack was never the inspiration of courage, but the result of calculation. His idea of the best defence consists in being still the attacking party. “My ambition,” he says, “was great, but was of a cold nature.” (75) In one of his conversations with Las Cases, he remarked, “As to the moral courage, I have rarely met with the two-o’clock-in-the-morning kind. I mean unprepared courage; that which is necessary on an unexpected occasion, and which, in spite of the most unforeseen events, leaves full freedom of judgement and decision:” (76) and he did not hesitate to declare that he was himself eminently endowed with this the two-o’clock-in-the-morning courage, and that he had met few persons equal to himself in this respect. (77)

Every thing depended on the nicety of his combinations, and the stars were not more punctual than his arithmetic. His personal attention descended to the smallest particulars. (78) “At Montebello, I ordered Kellermann to attack with eight hundred horse, and with these he separated the six thousand Hungarian grenadiers, before the very eyes of the Austrian cavalry. This cavalry was half a league off and required a quarter of an hour to arrive on the field of action, and I have observed that it is always these quarters of an hour that decide the fate of a battle.” (79) “Before he fought a battle, Bonaparte thought little about what he should do in case of success, but a great deal about what he should do in case of a reverse of fortune.” (80) The same prudence and good sense mark all his behavior. His instructions to his secretary (81) at the Tuileries are worth remembering. “During the night, enter my chamber as seldom as possible. Do not awake me when you have any good news to communicate; with that there is no hurry. But when you bring bad news, rouse me instantly, for then there is not a moment to be lost.” (82) It was a whimsical economy of the same kind which dictated his practice, when general in Italy, in regard to his burdensome correspondence. He directed Bourrienne to leave all letters unopened for three weeks, and then observed with satisfaction how large a part of the correspondence had thus disposed of itself and no longer required an answer. (83) His achievement of business was immense, and enlarges the known powers of man. There have been many working kings, from Ulysses to William of Orange, but none who accomplished a tithe of this man’s performance.

To these gifts of nature, Napoleon added the advantage of having been born to a private and humble fortune. (84) In his later days he had the weakness of wishing to add to his crowns and badges (85) the prescription of aristocracy; (86) but he knew his debt to his austere education, and made no secret of his contempt for the born kings, and for “the hereditary asses,” as he coarsely styled the Bourbons. (87) He said that “in their exile they had learned nothing, and forgot nothing.” (88)

Bonaparte had passed through all the degrees of military service, but also was citizen before he was emperor, and so has the key to citizenship. His remarks and estimates discover the information and justness of measurement of the middleclass. Those who had to deal with him found that he was not to be imposed upon, but could cipher as well as another man. (89) This appears in all parts of his Memoirs, dictated at St. Helena. When the expenses of the empress, of his household, of his palaces, had accumulated great debts, Napoleon examined the bills of the creditors himself, detected overcharges and errors, and reduced the claims by considerable sums. (90)

His grand weapon, namely the millions whom he directed, he owed to the representative character which clothed him. He interests us as he stands for France and for Europe; and he exists as captain and king only as far as the Revolution, or the interest of the industrious masses, found an organ and a leader in him. In the social interests, he knew the meaning and value of labor, and threw himself naturally on that side. I like an incident mentioned by one of his biographers at St. Helena. “When walking with Mrs. Balcombe, some servants, carrying heavy boxes, passed by on the road, and Mrs. Balcombe desired them, in rather an angry tone, to keep back. Napoleon interfered, saying ‘Respect the burden, Madam.’” (91) In the time of the empire he directed attention to the improvement and embellishment of the markets of the capital. “The market-place,” he said, “is the Louvre of the common people.” (92) The principal works that have survived him are his magnificent roads. (93) He filled the troops with his spirit, and a sort of freedom and companionship grew up between him and them, (94) which the forms of his court never permitted between the officers and himself. They performed, under his eye, that which no others could do. (95) The best document of his relation to his troops is the order of the day on the morning of the battle of Austerlitz, in which Napoleon promises the troops that he will keep his person out of reach of fire. (96) This declaration, which is the reverse of that ordinarily made by generals and sovereigns on the eve of a battle, sufficiently explains the devotion of the army to their leader.

But though there is in particulars this identity between Napoleon and the mass of the people, his real strength lay in their conviction that he was their representative in his genius and aims, not only when he courted, but when he controlled, and even when he decimated them by his conscriptions. Heknew, as well as any Jacobin in France, how to philosophize on liberty and equality; (97) and when allusion was made to the precious blood of centuries, which was spilled by the killing of the Duc d’Enghien, he suggested, “Neither is my blood ditchwater.” (98) The people felt that no longer the throne was occupied and the land sucked of its nourishment, by a small class of legitimates, secluded from all community with the children of the soil, and holding the ideas and superstitions of a long-forgotten state of society. Instead of that vampyre, a man of themselves held, in the Tuileries, knowledge and ideas like their own, opening of course to them and their children all places of power and trust. The day of sleepy, selfish policy, ever narrowing the means and opportunities of young men, was ended, and a day of expansion and demand was come. A market for all the powers and productions of man was opened; brilliant prizes glittered in the eyes of youth and talent. (99) The old, iron-bound, feudal France was changed into a young Ohio or New York; and those who smarted under the immediate rigors of the new monarch, pardoned them as the necessary severities of the military system which had driven out the oppressor. And even when the majority of the people had begun to ask whether they had really gained any thing under the exhausting levies of men and money of the new master, the whole talent of the country, in every rank and kindred, took his part and defended him as its natural patron. In 1814, when advised to rely on the higher classes, Napoleon said to those around him, “Gentlemen, in the situation in which I stand, my only nobility is the rabble of the Faubourgs.” (100)

Napoleon met this natural expectation. The necessity of his position required a hospitality to every sort of talent, (101) and its appointment to trusts; and his feeling went along with this policy. Like every superior person, he undoubtedly felt a desire for men and compeers, and a wish to measure his power with other masters, and an impatience of fools and underlings. In Italy, he sought for men and found none. “Good God!” he said, “how rare men are! There are eighteen millions in Italy, and I have with difficulty found two,-Dandolo and Melzi.” (102) In later years, with larger experience, his respect for mankind was not increased. (103) In a moment of bitterness he said to one of his oldest friends, “Men deserve the contempt with which they inspire me. I have only to put some gold-lace on the coat of my virtuous republicans and they immediately become just what I wish them.” (104) This impatience at levity was, however, an oblique tribute of respect to those able persons who commanded his regard not only when he found them friends and coadjutors but also when they resisted his will. He could not confound Fox and Pitt, Carnot, Lafayette and Bernadotte, with the danglers of his court; (105) and in spite of the detraction which his systematic egotism (106) dictated toward the great captains who conquered with and for him, ample acknowledgments are made by him to Lannes, (107) Duroc, (108) Kleber, (109) Dessaix, (110) Massena, (111) Murat, (112) Ney (113) and Augereau. (114) If he felt himself their patron and the founder of their fortunes, as when he said, “I made my generals out of mud,”- (115) he could not hide his satisfaction in receiving from them a seconding and support commensurate with the grandeur of his enterprise. In the Russian campaign he was so much impressed by the courage and resources of Marshal Ney, that he said, “I have two hundred millions in my coffers, and I would give them all for Ney.” (116) The characters which he has drawn of several of his marshals are discriminating, and though they did not content the insatiable vanity of French officers, are no doubt substantially just. And in fact every species of merit was sought and advanced under his government. “I know,” he said, “the depth and draught of water of every one of my generals.” (117) Natural power was sure to be well received at his court. Seventeen men in his time were raised from common soldiers to the rank of king, marshal, duke, or general; (118) and the crosses of his Legion of Honor were given to personal valor, (119) and not to family connexion. “When soldiers have been baptized in the fire of a battlefield, they have all one rank in my eyes.” (120)

When a natural king becomes a titular king, every body is pleased and satisfied. (121) The Revolution entitled the strong populace of the Faubourg St. Antoine, and every horse-boy and powder-monkey in the army, to look on Napoleon as flesh of his flesh and the creature of his party: but there is something in the success of grand talent which enlists an universal sympathy. For in the prevalence of sense and spirit over stupidity and malversation, all reasonable men have an interest; and as intellectual beings we feel the air purified by the electric shock, when material force is overthrown by intellectual energies. As soon as we are removed out of the reach of local and accidental partialities, Man feels that Napoleon fights for him; these are honest victories; this strong steam engine does our work. (122) Whatever appeals to the imagination, by transcending the ordinary limits of human ability, wonderfully encourages us and liberates us. This capacious head, revolving and disposing sovereignly trains of affairs, and animating such multitudes of agents; this eye, which looked through Europe; this prompt invention; this inexhaustible resource:- what events! what romantic pictures! what strange situations!- when spying the Alps, by a sunset in the Sicilian sea; (123) drawing up his army for battle in sight of the Pyramids, and saying to his troops, “From the tops of those pyramids, forty centuries look down on you”; (124) fording the Red Sea; wading in the gulf of the Isthmus of Suez. (125) On the shore of Ptolemais, gigantic projects agitated him. (126) “Had Acre fallen, I should have changed the face of the world.” (127) His army, on the night of the battle of Austerlitz, which was the anniversary of his inauguration as Emperor, presented him with a bouquet of forty standards taken in the fight. (128) Perhaps it is a little puerile, the pleasure he took in making these contrasts glaring; as when he pleased himself with making kings wait in his antechambers, at Tilsit, at Paris and at Erfurt. (129)

We can not, in the universal imbecility, indecision and indolence of men, (130) sufficiently congratulate ourselves on this strong and ready actor, who took occasion by the beard, and showed us how much may be accomplished by the mere force of such virtues as all men possess in less degrees; namely, by punctuality, by personal attention, by courage and thoroughness. “The Austrians,” he said, “do not know the value of time.” (131) I should cite him, in his earlier years, as a model of prudence. His power does not consist in any wild or extravagant force; in any enthusiasm like Mahomet’s, (132) or singular power of persuasion; but in the exercise of common- sense on each emergency, instead of abiding by rules and customs. The lesson he teaches is that which vigor always teaches;- that there is always room for it. (133) To what heaps of cowardly doubts is not that man’s life an answer. When he appeared it was the belief of all military men that there could be nothing new in war; (134) as it is the belief of men to-day that nothing new can be undertaken in politics, or in church, or in letters, or in trade, or in farming, or in our social manners and customs; and as it is at all times the belief of society that the world is used up. But Bonaparte knew better than society; and moreover knew that he knew better. I think all men know better than they do; know that the institutions we so volubly commend are go-carts and baubles; but they dare not trust their presentiments. Bonaparte relied on his own sense, and did not care a bean for other people’s. The world treated his novelties just as it treats everybody’s novelties,- made infinite objection, mustered all the impediments; but he snapped his finger at their objections. “What creates great difficulty,” he remarks, “in the profession of the land-commander, is the necessity of feeding so many men and animals. If he allows himself to be guided by the commissaries he will never stir, and all his expeditions will fail.” (135) An example of his common-sense is what he says of the passage of the Alps in winter, which all writers, one repeating after the other, had described as impracticable. “The winter,” says Napoleon, “is not the most unfavorable season for the passage of lofty mountains. The snow is then firm, the weather settled, and there is nothing to fear from avalanches, the real and only danger to be apprehended in the Alps. On these high mountains there are often very fine days in December, of a dry cold, with extreme calmness in the air.” (136) Read his account, too, of the way in which battles are gained. “In all battles a moment occurs when the bravest troops, after having made the greatest efforts, feel inclined to run. That terror proceeds from a want of confidence in their own courage, and it only requires a slight opportunity, a pretence, to restore confidence to them. The art is, to give rise to the opportunity and to invent the pretence. At Arcola I won the battle with twenty-five horsemen. I seized that moment of lassitude, gave every man a trumpet, and gained the day with this handful. You see that two armies are two bodies which meet and endeavor to frighten each other; a moment of panic occurs, and that moment must be turned to advantage. When a man has been present in many actions, he distinguishes that moment without difficulty: it is as easy as casting up an addition.” (137)

This deputy of the nineteenth century added to his gifts a capacity for speculation on general topics. He delighted in running through the range of practical, of literary and of abstract questions. His opinion is always original and to the purpose. On the voyage to Egypt he liked, after dinner, to fix on three or four persons to support a proposition, and as many to oppose it. He gave a subject, and the discussions turned on questions of religion, the different kinds of government, and the art of war. One day he asked whether the planets were inhabited? On another, what was the age of the world? Then he proposed to consider the probability of the destruction of the globe, either by water or by fire: at another time, the truth or fallacy of presentiments, and the interpretation of dreams. (138) He was very fond of talking of religion. (139) In 1806 he conversed with Fournier, bishop of Montpellier, on matters of theology. There were two points on which they could not agree, viz. that of hell, and that of salvation out of the pale of the church. The Emperor told Josephine that he disputed like a devil on these two points, on which the bishop was inexorable. (140) To the philosophers he readily yielded all that was proved against religion as the work of men and time, but he would not hear of materialism. One fine night, on deck, amid a clatter of materialism, (141) Bonaparte pointed to the stars, and said, “You may talk as long as you please, gentlemen, but who made all that?” (142) He delighted in the conversation of men of science, particularly of Monge and Berthollet; (143) but the men of letters he slighted; they were “manufacturers of phrases.” (144) Of medicine too he was fond of talking, and with those of its practitioners whom he most esteemed,- with Corvisart at Paris, and with Antonomarchi at St. Helena. “Believe me,” he said to the last, “we had better leave off all these remedies: life is a fortress which neither you nor I know any thing about. Why throw obstacles in the way of its defence? Its own means are superior to all the apparatus of your laboratories. Corvisart candidly agreed with me that all your filthy mixtures are good for nothing. Medicine is a collection of uncertain prescriptions, the results of which, taken collectively, are more fatal than useful to mankind. Water, air and cleanliness are the chief articles in my pharmacopoeia.” (145)

His memoirs, dictated to Count Montholon and General Gourgaud at St. Helena, (146) have great value, after all the deduction that it seems is to be made from them on account of his known disingenuousness. (147) He has the good-nature of strength and conscious superiority. I admire his simple, clear narrative of his battles;- good as Caesar’s; his good-natured and sufficiently respectful account of Marshal Wurmser (148) and his other antagonists; and his own equality as a writer to his varying subject. The most agreeable portion is the Campaign in Egypt. (149)

He had hours of thought and wisdom. In intervals of leisure, either in the camp or the palace, Napoleon appears as a man of genius directing on abstract questions the native appetite for truth and the impatience of words he was wont to show in war. He could enjoy every play of invention, a romance, a bon mot, (150) as well as a strategem in a campaign. He delighted to fascinate Josephine and her ladies, in a dimlighted apartment, by the terrors of a fiction to which his voice and dramatic power lent every addition. (151)

I call Napoleon the agent or attorney of the middle class of modern society; of the throng who fill the markets, shops, counting-houses, manufactories, ships, of the modern world, aiming to be rich. He was the agitator, the destroyer of prescription, the internal improver, (152) the liberal, (153) the radical, the inventor of means, the opener of doors and markets, the subverter of monopoly and abuse. Of course the rich and aristocratic did not like him. England, the centre of capital, and Rome and Austria, centres of tradition and genealogy, opposed him. The consternation of the dull and conservative classes, the terror of the foolish old men and old women of the Roman conclave, who in their despair took hold of any thing, and would cling to red-hot iron,- the vain attempts of statists to amuse and deceive him, (154) of the emperor of Austria to bribe him; (155) and the instinct of the young, ardent and active men every where, which pointed him out as the giant of the middle class, make his history bright and commanding. He had the virtues of the masses of his constituents: he had also their vices. (156) I am sorry that the brilliant picture has its reverse. But that is the fatal quality which we discover in our pursuit of wealth, that it is treacherous, and is bought by the breaking or weakening of the sentiments; and it is inevitable that we should find the same fact in the history of this champion, who proposed to himself simply a brilliant career, (157) without any stipulation or scruple concerning the means.

Bonaparte was singularly destitute of generous sentiments. The highest-placed individual in the most cultivated age and population of the world,- he has not the merit of common truth and honesty. He is unjust to his generals; (158) egotistic and monopolizing; meanly stealing the credit of their great actions from Kellermann, from Bernadotte; (159) intriguing to involve his faithful Junot in hopeless bankruptcy, in order to drive him to a distance from Paris, (160) because the familiarity of his manners offends the new pride of his throne. He is a boundless liar. (161) The official paper, his “Moniteur,” and all his bulletins, are proverbs for saying what he wished to be believed; (162) and worse,- he sat, in his premature old age, in his lonely island, coldly falsifying facts and dates and characters, and giving to history a theatrical éclat. (163) Like all Frenchmen he has a passion for stage effect. (164) Every action that breathes of generosity is poisoned by this calculation. His star, his love of glory, his doctrine of the immortality of the soul, (165) are all French. “I must dazzle and astonish. If I were to give the liberty of the press, my power could not last three days.” (166) To make a great noise is his favorite design. “A great reputation is a great noise: the more there is made, the farther off it is heard. Laws, institutions, monuments, nations, all fall; but the noise continues, and resounds in after ages.” (167) His doctrine of immortality is simply fame. (168) His theory of influence is not flattering. “There are two levers for moving men,- interest and fear. (169) Love is a silly infatuation, depend upon it. (170) Friendship is but a name. I love nobody. I do not even love my brothers: perhaps Joseph a little, from habit, and because he is my elder; and Duroc, I love him too; but why?- because his character pleases me: he is stern and resolute, and I believe the fellow never shed a tear. (171) For my part I know very well that I have no true friends. As long as I continue to be what I am, I may have as many pretended friends as I please. Leave sensibility to women; but men should be firm in heart and purpose, or they should have nothing to do with war and government.” (172) He was thoroughly unscrupulous. He would steal, slander, assassinate, drown and poison, as his interest dictated. (173) He had no generosity, but mere vulgar hatred; he was intensely selfish; (174) he was perfidious; he cheated at cards; (175) he was a prodigious gossip, and opened letters, and delighted in his infamous police, (176) and rubbed his hands with joy when he had intercepted some morsel of intelligence concerning the men and women about him, boasting that “he knew every thing”; (177) and interfered with the cutting the dresses of the women; (178) and listened after the hurrahs and the compliments of the street, incognito. (179) His manners were coarse. He treated women with low familiarity. (180) He had the habit of pulling their ears and pinching their cheeks when he was in good humor, and of pulling the ears and whiskers of men, (181) and of striking and horse-play with them, to his last days. It does not appear that he listened at key-holes, or at least that he was caught at it. In short, when you have penetrated through all the circles of power and splendor, you were not dealing with a gentleman, at last; but with an impostor and a rogue; and he fully deserves the epithet of Jupiter Scapin, or a sort of Scamp Jupiter. (182)

In describing the two parties into which modern society divides itself,- the democrat and the conservative,- I said, Bonaparte represents the democrat, or the party of men of business, against the stationary or conservative party. I omitted then to say, what is material to the statement, namely that these two parties differ only as young and old. The democrat is a young conservative; the conservative is an old democrat. (183) The aristocrat is the democrat ripe and gone to seed;- because both parties stand on the one ground of the supreme value of property, which one endeavors to get, and the other to keep. Bonaparte may be said to represent the whole history of this party, its youth and its age; yes, and with poetic justice its fate, in his own. The counter-revolution, the counter-party, still waits for its organ and representative, (184) in a lover and a man of truly public and universal aims.

Here was an experiment, under the most favorable conditions, of the powers of intellect without conscience. (185) Never was such a leader so endowed and so weaponed; never leader found such aids and followers. And what was the result of this vast talent and power, of these immense armies, burned cities, squandered treasures, immolated millions of men, of this demoralized Europe? It came to no result. All passed away like the smoke of his artillery, and left no trace. He left France smaller, poorer, feebler, than he found it; (186) and the whole contest for freedom was to be begun again. (187) The attempt was in principle suicidal. France served him with life and limb and estate, as long as it could identify its interest with him; but when men saw that after victory was another war; after the destruction of armies, new conscriptions; and they who had toiled so desperately were never nearer to the reward,- they could not spend what they had earned, nor repose on their down-beds, nor strut in their chateaux,- they deserted him. Men found that his absorbing egotism was deadly to all other men. It resembled the torpedo, which inflicts a succession of shocks on any one who takes hold of it, producing spasms which contract the muscles of the hand, so that the man can not open his fingers; and the animal inflicts new and more violent shocks, until he paralyzes and kills his victim. So this exorbitant egotist narrowed, impoverished and absorbed the power and existence of those who served him; and the universal cry of France and of Europe in 1814 was, “Enough of him”; “Assez de Bonaparte.” (188)

It was not Bonaparte’s fault. He did all that in him lay to live and thrive without moral principle. (189) It was the nature of things, the eternal law of man and of the world (190) which baulked and ruined him; and the result, in a million experiments, will be the same. Every experiment, by multitudes or by individuals, that has a sensual and selfish aim, will fail. The pacific Fourier will be as inefficient as the pernicious Napoleon. As long as our civilization is essentially one of property, of fences, of exclusiveness, it will be mocked by delusions. Our riches will leave us sick; there will be bitterness in our laughter, and our wine will burn our mouth. Only that good profits which we can taste with all doors open, and which serves all men.

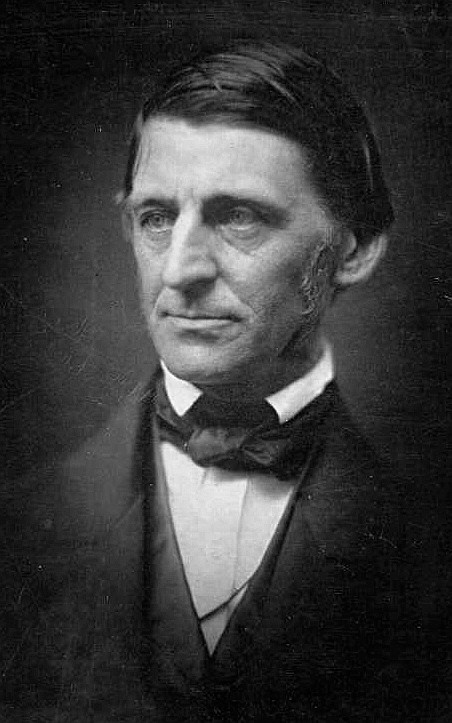

Notes by Frank Davidson, Professor of English, Indiana University, published in Indiana University Publications, Humanities Series No. 16, 1947, "Napoleon or The Man of the World, by Ralph Waldo Emerson".

1 – For other expressions of Emerson's concerning this representative quality of a great man, see "Plato; or, the Philosopher," Complete Works, IV, 41; "Swedenborg; or, the Mystic," ibid, IV, 103-104; and "Shakespeare; or, the Poet," ibid IV, 189-190. Emerson had been building toward such a view in the Journals, II, 101 (1826); II, 282 (1830); IV, 60-61 (1836); IV, 187-188 (1837); V, 360-361 (1839); V, 369 (1840).

2 – See Emerson's essay on Swedenborg, Complete Works, IV, 113-114, where Emerson quotes Lucretius and Swedenborg concerning the theory of tota in minimis existit Natura.

3 – Emerson returns to his distinction of conservative and democrat near the close of the essay, Complete Works, IV, 256. He had made preparation in the Journals, VI, 52, 100, 142 (1841); VI, 221-222 (1842); and in his essays "The Conservative" and "Lecture on the Times," Complete Works, I, 295-326 and 259-291 respectively. Both were of 1841. Part of the admiration of Carlyle, Hazlitt, Emerson, and others for Napoleon, especially the youthful Napoleon, was due to his liberal views; he represented for them the "party of the Future" rather than the "party of the Past"; the "indisputable infinitude" rather than the "confessed limitations" of man.

4 – For Emerson's views on economics, see Alexander C. Kern's study "Emerson and Economics," The New England Quarterly, XIII (December, 1940), 678-696.

5 – Statements of belief in Napoleon's democratic leanings, especially during his early period in French politics, may be found in Thomas Carlyle, The Works of Thomas Carlyle, V, 207-208, where Carlyle quotes an epithet that had been applied to Napoleon-"armed soldier of Democracy." See, too, The Complete Works of William Hazlitt, ed. P. P. Howe (London, 1931), XIII, ix-x. Subsequent references to Hazlitt will be to this edition. Hazlitt speaks here of admiring Napoleon because he was the child and the champion of the Revolution; because he stood between the divine-rightists and their natural prey. "This was the chief point at issue,-" he says; "this was the great question, compared with which all others were tame and insignificant-whether mankind were from the beginning to the end of time, born slaves or not." Cf. notes 18 and 94 below.

6 – Emerson, Journals, IV, 95 (1836), and "Literary Ethics", Complete Works, I, 179-181.

7 – Journals, II, 89 (1826). Nineteen years before he wrote the lecture on Napoleon Emerson was beginning to develop the idea of a universal element in individual experience. History, he wrote, with its account of the experience of the ages, helps us to find the human principle which plays through all and so to find a rule of life. "In this way Moses and Solomon, Alcibiades and Bonaparte have existed for me; the fortunes of Assyria, of Athens and of Rome have not become a dead letter-have not fulfilled their effect in the universe, till they have taught me and you, and all men to whose ears these names may come, all the lessons of manners, of political and religious causes, and of a high paramount Providence which the great scripture of a nation's history contains." For a somewhat steady development of the idea, see Journals, II, 215 (1827); III, 249 (1834); "History" (1814), Complete Works, II, 3-41; and Journals, VI, 507, 514 (1844).

8 – Bourrienne, Memoirs, I, 113: "He [Napoleon] has often said to me, 'I am no Capuchin, not I.'"

9 – Emerson reported of the reception of his lecture on Napoleon at one city of England: "Mr. Kehl thought that my lecture on Napoleon was not true for the operatives who heard it at Huddersfield, but was true only for the commercial classes, and for the Americans, no doubt; that the aim of these operatives was to get twenty shillings a week, and to marry; then they join the 'Mechanics Institute', hear lectures, visit the new-room, and desire no more." Journals, VII, 381-382 (1848).

10 – Pierre Etienne Louis Dumont, Recollections of Mirabeau (Philadelphia, 1833). Emerson mentioned the author in Journals, III, 288 (1834).

11 – Dumont, op. cit., pp. 96-97. Emerson keeps the gist of the story; he makes but slight changes in the quoted matter.

12 – See Journals, II, 101 (1826), and III, 329 (1834). In the first of these references Emerson credits Edward Everett with lodging the idea with him; in the second he says: "It is not an individual, but the general mind of man that speaks from time to time, quite careless and quite forgetful of what mouth or mouths it makes use of."

13 – Lockhart, The History of Napoleon Buonaparte, II, 45: "The Code Napoleon, That elaborate system of jurisprudence in the formation of which the Emperor laboured personally along with the most eminent lawyers and enlightened men of the time, was a boom of inestimable value to France….It was the first uniform system of laws which the French Monarchy had ever possessed; and being drawn up with consummate skill and wisdom, it at this day [1829] forms the code not only of France, but of a great portion of Europe besides." See, too, Bourrienne, op. cit., II, 118.

14 – For the confusion in weights and measures to which Napoleon gave order, see A Memoir of the History of France, IV, 200-2006.

15 – Autommarchi, The Last Days of the Emperor Napoleon, I, 349. In a summary of some of Napoleon's achievements Autommarchi uses the expression "The Alps levelled!"

16 – Lockhart, op. cit., I, 229. Emerson recorded in Journals, III, 148, an account of the day, June 12, 1833, he spent crossing the Alps by the Simplon Road, "cut and built by Bonaparte… a glory to his name, him the great Hand of our age." See Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 339, for an account of Napoleon's roads in Savoy and on Mt. Cenis.

17 – Carlyle in The French Revolution, III, 173, states: "This Napoleon … not only fights, but writes; …"

18 – Hazlitt, Complete Works, XV, 235, quotes Napoleon: "The popular fibre responds to mine. I have arisen from the ranks of the people: my voice acts mechanically upon them. Look at those conscripts, the sons of peasants: I never flattered them; I treated them roughly. They did not crowd round me the less; they did not for that cease to cry, Vive l'Empereur! It is that between them and me there is one and the same nature." See, too, Las Cases, Memoirs of the Life, Exile, and Conservations of the Emperor Napoleon, II, 12.

19 – Unidentified quotation.

20 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 316, explains: "The word ideologue was often in Bonaparte's mouth; and in using it he endeavoured to throw ridicule on those men whom he fancied to have a tendency towards the doctrine of indefinite perfectibility. He esteemed them for their morality, yet he looked on them as dreamers, seeking for the type of a universal constitution, and considering the character character of man in the abstract only. The ideologues, according to him, looked for power in institutions; and that he called metaphysics. He had no idea of power, except in direct force." See also Joseph Fouché, The Memoirs of Joseph Fouché, II, 126, and Madame Staël, Oeuvres complètes, XIII, 401. In 1841 Emerson Made a note in his Journals, VI, 85-86, Concerning Napoleon's dislike of ideologists.

21 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 357.

22 – The thought is implied in a statement to Bourrienne concerning Lafayette: "Lafayette may be right in theory after all? An absurdity, when it is endeavoured to apply it to masses of men." Bourrienne, op. cit.

23 – There is a personal note here; Emerson had written in his Journals, IV, 437-438 (April, 1838): "The advantage of the Napoleon temperament, impassive, unimpressible by others, is a signal convenience over this other tender one, which every aunt and every gossiping girl can daunt and tether. This weakness, be sure, is merely cutaneous, and the sufferer gets his revenge by the sharpened observation that belongs to such sympathic fibre, as even in college I was already content to be "screwed" in the recitation room, if, on my return, I could accurately paint the fact in my youthful journal."

24 - Carlyle, The French Revolution III, 318. Carlyle speaks of Napoleon as "a man of head, a man of action".

25 – Journals, IV, 456, speaks of Emerson's "wicked pleasure" in Kant's observation that "detestable was be society of mere literary men." See, too, Journals, VI, 339 (1843).

26 – See Journals, VII, 24 (1845) for what amounts to a first draft.

27 – Loc. cit. Here again in the Journals Emerson writes what is practically a first draft of the passage as it appears in the essay.

28 – For Napoleon's arithmetical ability, see Las Cases, op. cit., I, 372-373; Lockhart, op. cit., II, 45; and Carlyle, The French Revolution, II, 77-78. Carlyle speaks of Napoleon's coming from the school at Brienne, "qualified by La Place". At Brienne he had been a student of mathematics under Pichegru, who later became one of his generals. Ibid., III, 240. In preparation for his interpretation of Bonaparte as a calculator, Emerson had entered in his Journals, VII, 11 (1845): "But this ciphering is especially French; Fourier is another arithmetician. La Place, Lagrange, Berthollet,-walking metres and destitute of worth. These cannot say to men of talents, I am that which these express, as Character always seems to say."

29 Philippe Paul Comte de Ségur, History of the Expedition to Russia, I, 192. Ségur, after speaking of Napoleon's addressing on one day eight letters to the Prince of Eckmuhl, stated that "In some of these he ordered that everything should move towards him, in conformity with his principle, 'that the art of war is merely the art of collecting more men upon any given point than the enemy.'" See, too, Sir Walter Scott, Life of Napoleon Buonaparte, I, 302-303, and III, 359, where Scott writes: "His system was, of course, that of assembling the greatest possible force of his own upon the vulnerable point of the enemy's position, paralyzing, perhaps, two parts of their army, whilst he cut the third to pieces, and them following up his position by destroying the remainder in detail."

30 – Lockhart, op. cit., I, 31.

31 – For Napoleon's advice about moving troops at an angle, see The Confidential Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte with His Brother Joseph, I, 168, 169, 174, 177, and Lockhart, op. cit., II, 100. Cf. Emerson's "Eloquence," Complete Works, VII, 84.

32 – Lockhart, op. cit., II, 8, 214. See quotation from Scott in note 29 above.

33 – The general theorizing in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries on the influence of nature and of natural laws on the affaires of men is too well know to need comment here. Emerson's first published essay was called Nature. Barry Edward O'Meara, Napoleon in Exile, II, 17, quotes Napoleon: "Unless nature forms a man of so peculiar a stamp as to be enabled to see and two years of age, but nature made me different from most others." On this point, see also Charles Maxime de Villemarest, Life of Prince Talleyrand, II, 217, and Lockhart, op. cit., I, 207: "When Nature has work to be done, she creates a genius to do it."

34 – See Emerson, "The Method of Nature" (1841), Complete Works, I, 207: "When Nature has work to be done, she creates a genius to do it.

35 – Emerson had entered in his Journals, IV, 477-478 (1838): "Health. We must envy the great spirits their great physique. Goethe and Napoleon and Humboldt and Scott,-what though bodies answered to their unweariable souls! … The iron hand must have an iron arm." For testimony as to Napoleon's endurance, see Las Cases, op. cit., I, 235-236: Lockhart, op. cit., I, 59, 119-120, 223-224; Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 278; and O'Meara, op. cit., I, 192-193: "He [Napoleon] told me that he had frequently laboured in state affairs for fifteen hours, without a moment's cessation, or even having taken any nourishment. On one occasion, he had continued at his labours for three days and nights, without laying [sic] down to sleep."

36 – Quoted with slight variation from Las Cases, op. cit., IV, 178. Emerson had copied the quotation into his Journals, IV, 463 (June, 1838).

37 – Las Cases, op. cit., IV, 178, writes: "On a certain occasion, it was observed to the Emperor that he was not fond of putting forward his own merits; "That is," replied he, "because with me morality and generosity are not in my mouth, but in my nerves."

38 – For Napoleon belief in his star and in destiny, see Armand Augustin Louis de Caulincourt, Recollections of Caulaincourt, I, 22; O'Meara, op. cit., I, 230; II, 152; Ségur, op. cit., II, 271; Madame de Staël, op. cit., XIII, 269; Lockhart, op. cit., II, 148; and Hazlitt, op. cit., XIV, 104.

39 - Fouché states in his Memoirs, I, 303: "She [France] prided herself upon having been saluted with the name of the great nation by her emperor, who had triumphed over the genius and the work of Frederic; and Napoleon believed himself the son of Destiny, called to break every sceptre." See, also, ibid., II, 112, and Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 136: "He relied much on fortune …"

40 – O'Meara, op. cit., I, 248, quotes Napoleon: "They will say, "It is true that he has raised himself to the highest pinnacle of glory, mais pour y arriver, il commit beaucoup de crimes…" Now the fact is, that I not only never committed any crimes, but I never even thought of doing so."

41 – Emerson had written in his Journals, IV, 471 (1838): "Great men … do not brag of their personal attributes, but, like Napoleon, generously belong to the connexion of events. He identified himself with the new age, and owned himself the passive organ of an idea." Las Cases, op. cit., IV, 174, quoted Napoleon, who was talking at the time on equality: "It is the passion of the age; and I wish to continue to be the man of the age." See, too, O'Meara, op. cit., I, 248-249, who attributes to Napoleon the statement: "J'ai toujours marché avec l'opinion les grandes masses et les évènements…"

42 – O'Meara, loc. cit.; "… of what use, then, would crime have been to me?"

43 – Unidentified quotation.

44 – Carlyle had written of Napoleon: "Taciturn; yet with the strangest utterances in him, if you awaken him, which smite home, like light on lightning;-on the whole, rather dangerous? A "dissocial" man? Dissocial enough; a natural terror and horror to all Phantasms, being himself of the genus Reality!" The French Revolution, III, 293.

45 – Emerson had meditated this idea; he quotes in the Journals once, V, 371 (1840), from Balzac's Le Livre Mystique: "Les évènements ont des causes dans lesquelles ils sont préconçus, comme nos actions sont accomplies dans notre pensée, avant de se reproduire en dehors;…" Again he stated, Journals, VII, 11 (1845) : "Napoleon was entitled to his crowns; he won his victories in his head before he won them on the field. He was not lucky only." Caulincourt, in his Recollections, I, 15, reports an incident from the battle of Bautzen. He had reminded Napoleon of lack of rest and of the difficulties of the day ahead. "Impossible, Caulincourt," the Emperor had replied; "I have my plan here," said he, passing his hand lightly across his forehead, …" See also The Confidential Correspondence, I, 141-142: "In war nothing is to be done but by calculation. Whatever is not profoundly considered in its details produces no good result." And Scott distinguishes Napoleon from the generals who "stumble unexpectedly on victory". The life of Napoleon, I, 311.

46 – Bourrienne, op. cit., II, 163. Napoleon wished it known that he stood in need of nobody.

47 – Emerson quotes verbatim from A Memoir of the History of France, IV, 473.

48 – The Duchesse d'Abrantès, wife of General Junot, wrote after seeing the mad queen of Portugal: "When, on my return home, I mentioned my adventure to Junot, we could not help remarking the curious fact that all the Sovereigns of Europe-at least, all the legitimate Sovereigns-were at that time either mad or imbecile." Memoirs of the Emperor Napoleon, II, 317. See, too, Emerson's "Manners." Complete Works, III, 128 (1844).

49 – Emerson was probably generalizing from his reading, though he may have profited from Caulincourt, op. cit., I, 20, or Hazlitt, op. cit., XIII, 225: "It is the fault of most generals that after a great battle gained, they are at a loss what to do, as it confounded by their own good luck, and unwilling to push their advantage to the utmost … Buonaparte had none of this timidity or doubt…" Cf. Carlyle, Works, V, 239: "…he, as every man that can be great, or have victory in this world, sees, through all entanglements, the practical heart of the matter; drives straight towards that."

50 – Cf. note 49 above and Scott, op. cit., I, 311: "But Buonaparte, who had foreseen the result of each operation by his sagacity, stood also prepared to make the most of the advantages which might be derived from it."

51 – Bourrienne says in his Memoirs, I, 228: "…if he [Napoleon] had defended, with all the influence of his glory, that liberty, which the nation claimed, and which the age demanded;-if he had rendered France as happy and free, as he rendered her glorious, posterity could not have refused him the very first place among the great men, at whose side he will be ranged." It is interesting to compare Dumont's statement concerning Mirabeau, Recollections, p. 83: "If Mirabeau had always served the public cause with the same ardour as he did that of his friend …he would have become the saviour of his country."

52 – A Memoir of the History of France, IV, 277. Emerson quoted verbatim a statement made by Napoleon in 1797, when a young general, Duphot, who was travelling in Rome, was murdered at the gate of the French palace while trying to prevent disorder. The quotation had been used by Hazlitt, op. cit., XIII, 322.

53 – A Memoir of the History of France, IV, 281. Emerson makes slight change in taking over the passage from a letter of Napoleon to the directory in 1797 when it had wished to declare war on Austria because of an insult offered the French ambassador, Bernadotte. The passage had been used by Hazlitt, op. cit., XIII, 324.

54 – Emerson perhaps remembered the statement in Bourrienne's Memoirs, II, 156: "… time was so precious to him [Napoleon], that he would have wished, as one may say, to shorten a straight line."

55 – Emerson had great respect for men of strong will. "When the will is strong," he wrote in 1833, "we inevitably respect it in man or woman," and the following day he continued his note, using Luther and Napoleon as better treatises on the will than Edwards's. Journals, III, 250.

56 – Bourienne, after mentioning the massacre at Jaffa by Napoleon's order, concluded: "War, unfortunately, presents too many occasions on which a law, immutable in all ages, and common to all nations, requires that private interests should be sacrificed to a great general interest, and that even humanity should be forgotten." Memoirs, I, 182. Bourrienne reports, too, the remarks of Josephine concerning Napoleon: "You know that he is not naturally cruel; …" Ibid., II, 252. Emerson, in Journals, VI, 343-344 and 434 (1843), excused certain derelictions in Webster, on the grounds of his contributions as a man of genius; he did this, too, for Goethe, Journals, VI, 544-545 (1844). See also "Aristocracy," Complete Works, X, 51-52: "To a right aristocracy, to Hercules, to Theseus, Odin, the Cid, Napoleon; to Sir Robert Walpole, to Fox, Chatham, Mirabeau, Jefferson, O'Connell; … of course everything will be permitted and pardoned,-gaming, drinking, fighting, luxury. These are the heads of party, who can do no wrong,-everything short of infamous crime will pass." William Ellery Channing expressed a view contrary to this in his essays on Napoleon. Works, I, 72-73.

57 – Emerson probably had in mind stories of the massacre of the garrison at Jaffa; the giving of opium to the French soldiers after the siege of Acre when, stricken with the plague or badly wounded, they could not be moved; the prosecution of Moreau; the assassination of the Duc d'Enghien.

58 – Bourrienne, op. cit., II, 98: "… he knew how to face obstacles, and had been accustomed to overcome them." Scott writes in his Life on Napoleon, I, 303: "It is true that the abandonment of every object, save success in the field, augmented frightfully all the usual horrors of war."

59 – The quotations come, perhaps, from some account of the battle of Lodi; as yet, they are unidentified.

60 – In this long quotation from Seruzier, Memoirs militaires, pp. 28-29, Emerson keeps to a close translation down to the word some in next to the last line. The editors of the Centenary edition of Emerson Complete Works indicate in a note of volume IV, page 364, Emerson's explanation of the word some: "As I quote at second hand, and cannot procure Seruzier, I dare not adopt the high figure I find." The figure is "quinze mille." A brief statement of the story told by Seruzier appears in Lockhart, op. cit., I, 298.

61 – Bourrienne in his Memoirs, I, 339, quotes Napoleon: "There are now no Alps." Emerson used a similar expression in March, 1845, in the Journals, VII, 10.

62 – Bourrienne, loc. cit.

63 - Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 282: "He [Napoleon] had it in his power to do much, for he risked every thing and spared nothing." Caulincourt objectifies this characteristic of Napoleon in his account of the Emperor's activities just before the battle of Dresden. Recollections, I, 207-210.

64 – This is a faith often voiced by Emerson: see Journals, II, 301 (1830), 521 (1832); III, 361 (1834); the poem "Written in Naples" (1833). One of his best expressions of it appears in "Self-Reliance" (1841), Complete Works, II, 50: "No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature."

65 – A Memoir of the History of France, IV, 321. Count de Montholon quotes Napoleon: "Generals are often deceived respecting the strength of the enemy they have to engage. Prisoners are only acquainted with their own corps; officers make very uncertain reports; hence an axiom adapted to all cases has been generally adopted: that an army ought always to be ready by day, by might, and at all hours, to make all the resistance it is capable of making."

66 – Ibid., III, 239. Napoleon illustrated his method with an account of his meeting with the Austrians under Wurmser, when the later descended the Adige and Lake Garda, with a superiority in soldiers of five to two. See, too, ibid., VI, 170; Ségur, op. cit., I, 192; and The Confidential Correspondence, I, 151, 171, 183, 189.

67 – Quoted almost verbatim from Las Cases, op. cit., IV, 176. Napoleon on this occasion was talking to some raw recruits for whom their colonel had apologized.

68 – There are many stories to illustrate this point. Napoleon told O'Meara of having eighteen or nineteen horses shot from under him. Napoleon in Exile, II, 131. He spoke to Las cases of two occasions on which he was almost taken prisoner by the Austrians, Memoirs, I, 246-247, 288; of two attempts to assassinate him. Ibid., II, 49ff.

69 – A memoir of the History of France, III, 362. Napoleon had maneuvered Marshal Alvinzi of Austria from his position at Caldiero to one with Arcole and a swamp in his rear. The French reached his rear without his knowing it and attacked Arcole. "Napoleon determined to try a last effort in person; he seized a flag, rushed on the bridge, and there planted it; the column he commanded had reached the middle of the bridge, when the flanking fire and the arrival of a division of the enemy frustrated the attack; the grenadiers at the head of the column, finding themselves abandoned by the rear, hesitated, but being hurried away in the flight, they persisted in keeping possession of their General; they seized by his arms and by his clothes, and dragged him along with them amidst the deal, the dying, and the smoke; he was precipitated into a morass, in which he sunk up to the middle, surrounded by the enemy. The grenadiers perceived that their General was in danger; a cry was heard of "Forward, soldiers, to save the General!" These brave men immediately turned back, ran upon the enemy, drove him beyond the bridge, and Napoleon was saved." Versions of this story appear in Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 387-388; O'Meara, op. cit., II, 130; Lockhart, op. cit., I, 69-70; Hazlitt, op. cit., XIII, 249.

70 – Scott, op. cit., I, 327-328, 339, 349-350.

71 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, ix.

72 – Quoted with slight variations from Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 281.

73 - Lockhart, op. cit., II, 376: "His heart was naturally cold."

74 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 350, quotes Bonaparte, as he was leaving for Italy: "Should anything happen, I shall be back again like a thunderbolt." See also Scott, op. cit., III, 359: "His manoeuvres on the field of battle had the promptness and decision of the thunderbolt."

75 – Madame de Staël, op. cit., XIII, 196: "Je sentais dans mon âme une épée froide et tranchante qui glaçait en blessant ; je sentais dans mon esprit une ironie profonde à laquelle rien de grand ni de beau, pas même sa propre, ne pouvait échapper; …" See also above, note 73.

76 – Quoted with slight variations from Las Cases, op. cit., I, 251. Cf. Emerson, Journals, VI, 36 (1841).

77 – Although quotation marks are omitted, this passage comes, with but slight change, from Las Cases, op. cit., I, 251: "He did not hesitate to declare that he was himself eminently gifted with the two o'clock in the morning courage, and that, in this respect, he had met with but few persons who were at all equal to him."

78 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 145, 212, 282; II, 152. See also The Confidential Correspondence, Which is filled with accounts of Napoleon's attention to detail: he advises his brother on the disposition of his troops, principles of warfare, rescue of troops, care of the sick, finances, means of keeping control of a conquered region, diplomacy.

79 – Unidentified quotation. Napoleon seems not to have been present at the battle of Montebello. Kellermann made his famous charge at Marengo shortly after. See Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 361-362.

80 – Quoted verbatim from Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 282.

81 – Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne. He had been a schoolmate of Napoleon's at Brienne, an associate in the early 1790's in Paris. He took service with Napoleon in Italy in April, 1797, and served as secretary until his dismissal in November, 1802. He later served as ambassador to Hamburg.

82 – Quoted verbatim from Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 279.

83 - Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 52-53: "To satisfy himself that people wrote too much, and lost, in trifling and useless answers, valuable time, to told me to open only the letters which came by extraordinary couriers, and to leave all the rest for three weeks in the basket. I declare that at the end of that time it was unnecessary to reply to four-fifths of these communications … when the general in chief compared the very small number of letters which it was necessary to answer with the large number which time alone had answered, he laughed heartily at his whimsical idea."

84 – Napoleon said to Las Cases on one occasion: "I am come from the ranks of the people, my voice has influence over them … between them and me there is an identity of nature; …" Memoirs, II, 12. See also ibid., II, 118, where Napoleon speaks to Sir Hudson Lowe of his early environment.

85 – Lockhart, op. cit., I, 230. The author speaks of Napoleon's noticing the attraction that star and crosses worn by a Russian ambassador had for the French people. We know that he have crowns to sisters and brothers.

86 – Madame de Staël makes much of this defection; see Oeuvres complètes, XIII, 272: "Le jour du concordat, Bonaparte se tendit à l'église de Notre-Dame dans les anciennes voitures du roi, avec les mêmes cochers, les mêmes valets de pied marchant à coté de la portière ; il se fit dire jusque dans le moindre détail toute l'étiquette de la cour; et, bien que premier consul d'une république, il s'appliqua tout cet appareil de la royauté. » See, also, ibid., XIII, 319-320; Fouché, op. cit., I, 294-295; and Lockhart, op. cit., I, 223, 302 and 303. Carlyle writes, Works, V, 241: "He apostatised from his old faith in Facts, took to believing in Semblances; strove to connect himself with the Austrian Dynasties, Popedoms, with the old false Feudalities which he once saw clearly to be false;-considered that he would found "his Dynasty" and so forth; that the enormous French Revolution meant only that!" See, too, Bourrienne, op. cit., II, 118-119, for an account of Napoleon's behaviour when, as consul, he went to preside over the senate.

87 – O'Meara, op. cit., I, 63. Napoleon, speaking of the old emigrants, said that they "hate and are jealous of all who are not hereditary asses like themselves." See, too, Antommarchi, op. cit., I, 190-191, and Caulaincourt, op. cit., I, 271.

88 – O'Meara, op. cit., I, 64; II, 92.

89 – Las Cases, op. cit., I, 372-373; II, 92-93; The Confidential Correspondence, I, 150-151; and Carlyle, Works, V, 239.

90 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 333. On setting extravagant debts of Josephine, Bourrienne says: "I availed myself fully of the first consul's permission, and spared neither reproaches nor menaces. I am ashamed to say that the greater part of the tradesmen were contented with the half of what they demanded." See, too, Villemarest, op. cit., III, 191-193.

91 – Las Cases, op. cit., I, 197. The story is told, too, by Hazlitt, op. cit., XV, 296; he drew heavily on Las Cases.

92 – Las Cases, op. cit., IV, 174: "The Emperor directed particular attention to the improvement and embellishment of the markets of the capital. He used to say, 'The market-place is the Louvre of the common people.'"

93 – Emerson, Journals, III, 148 (1833).

94 – In conversation with O'Meara about discipline on ships, Napoleon remarked: "Why, in my campaigns I used to go to the lines in the bivouacs, sit down with the meanest soldier, converse, laugh, and joke with him. I always prided myself on being l'homme du peuple (The man of the people)." O'Meara, op. cit., II, 146. Caulaincourt testifies also to the attachment of soldiers to their general: "It was curious to observe the attachment, confidence and familiarity, which existed between the humblest of the soldiers and the most absolute sovereign that ever existed. There was not one of Napoleon's intimate friends, however high in rank, who would have ventured to indulge in the sort of camaraderie which was kept up between the Emperor and his moustaches … He inspired them with a language which they addressed only to him, and words which they uttered only in his presence." Recollections, I, 218. See, too, Lockhart, op. cit., II, 326, and Hazlitt, op. cit., XIV, 45.

95 – Caulaincourt, op. cit., I, 221: "Our troops performed prodigies during the action. The officers could scarcely restrain the ardour of the men, who, without waiting the word of command, rushed headlong to the attack. Whilst he was looking on, the Emperor several times exclaimed enthusiastically, "What troops! These are mere raw recruits! It is incredible!'"

96 – In The History of Napoleon, I, 297, Lockhart tells of this incident: Napoleon had arisen at one o'clock on the morning on December 2, 1805, the day of the battle of Austerlitz. He was recognized by the soldiers, who received him with shouts of enthusiasm. "They reminded him that this was the anniversary of his coronation, and assured him they would celebrate the day in a manner worthy of its glory. "Only promise us," cried an old grenadier, "that you will keep yourself out of the fire." "I will do so," answered Napoleon, "I shall be with the reserve until you need us." This pledge, which so completely ascertains the mutual confidence of the leader and his soldiers, he repeated in a proclamation at daybreak. The sun rose with uncommon brilliancy: on many an after-day the French soldiery hailed a similar down with exultation as the sure omen of victory, and "the Sun of Austerlitz" had passed into a proverb."

97 – Emerson was probably recalling such passages as appear in Las Cases, op. cit., II, 12-13; IV, 174, 179; Lockhart, op. cit., I, 101; and Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 306, 318; II, 117. In this last reference Bourrienne says that when Napoleon was made consul for life he "did not fail to introduce the high-sounding words 'liberty and equality.'"

98 – In speaking of the conspiracies against him, of which he thought the Duc d'Enghien and his followers a part, Napoleon said: "I had never personally offended any of them; a great nation had chosen me to govern them; almost all Europe had sanctioned their choice; my blood, after all was not ditch-water; …" Las Cases, op. cit., IV, 191-192.

99 – Emerson probably had his suggestion from O'Meara, op. cit., I, 64, who quotes Napoleon: "Wherever I found talent and courage, I rewarded it. My principle was, la carrière ouvert au talens (the career open to talents), without asking whether there were any quarters of nobility to show." Carlyle, Works, V, 207, quoted the French phrase, translated it as "the tools to him who can handle them," and called the idea "our ultimate political Evangel, wherein alone can Liberty lie." See, also, O'Meara, op. cit., II, 116-117, 173, 227, and Lockhart, op. cit., II, 49,378.

100 – Quoted with slight variations from Bourrienne, op. cit., III, 294. The remark is assigned by Bourrienne to a longer statement made by Napoleon in January, 1814, when, pressed by the enemy, he was advised to rely on the notability.

101 – See note 99 above; Carlyle, Works, V, 239-240; and Scott, op. cit., III, 361. Scott writes: "Having therefore, attained the summit of human power, he [Napoleon] proceeded advisedly, and deliberately, to lay the foundation of his throne on that democratic principle which had opened his own career and which was the throwing open to merit, though without further title, the road to success in every department of the state. This was the secret key of Napoleon's policy …"

102 – Quoted verbatim from Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 52.

103 – Bourrienne, op. cit., I, 282.

104 – Quoted with slight variations from Bourrienne, op. cit., II, 83.