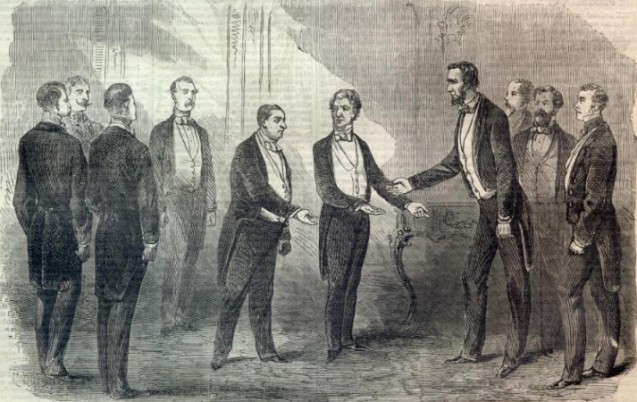

After a dreadful few months, in which scandal followed humiliation with respite, Prince Napoléon left Paris in the company of his wife, Clotilde, on 2 June and headed for the south, visiting the north African coast and Portugal before proceeding to the New World.

On 11 June, he arrived in La Goulette, the port serving the city of Tunis, and was met by an official party. Arriving in Tunis, he was welcomed with great pomp and ceremony by Sadok bey, the ruler of Tunis. Leaving Tunisia on 13 June, he carried on to Algeria, and landed in Bône (modern-day Annaba) a day later. The stopover included a visit to Alger, before the party left the country on 24 June. He moved on next to Morocco, visiting Tetouan, Tanger, and Cueta.

His African adventure came to an end on 28 June, and the party sailed for Cadiz, where a damaged keel was repaired in three days (the Spaniards, much to Plon-Plon’s surprise, worked through Sunday to get it done). The party took advantage of the enforced three-day stopover to visit Jerez de la Frontera and Seville; the ship subsequently sailed north for Lisbon, where Plon-Plon was received by the Portugeuse king, Pedro V. The party’s ship, Jerome-Napoleon, stopped in the Azores for three days before heading for the New World. A short, enforced layover in the French islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, off the coast of Newfoundland, was the last delay before the party finally arrived in the port of Halifax, Nova-Scotia, on 22 July. The young British prince, Alfred, Victoria’s second son, was by chance in Halifax at the same time and met the imperial couple.

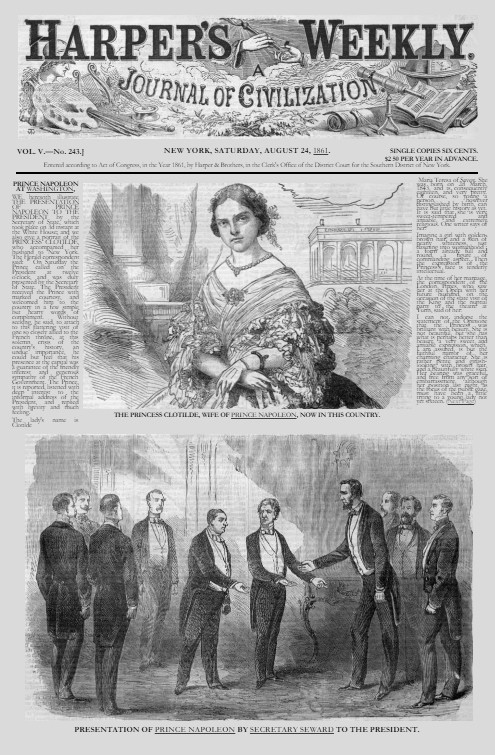

Jerome-Napoleon set sail for New York on 25 July: arriving on 27 July in the city, the party was met by France’s Consul General, Charles de Montholon, the French plenipotentiary to Washington, Henri Mercier de Lostende, and a throng of curious journalists. New York appealed little to Plon-Plon (“a large, sad city, with nothing picturesque or original to it: the English style, but on a larger scale,” he is said to have remarked), and on 3 August, the party arrived in Washington for an unofficial visit to the White House. It was to prove an utter fiasco. Harper’s Weekly, A journal of civilization (vol. V, no. 243, 24 August 1861) offered a sanitised, stately account:

“On Saturday the Prince called on the President at twelve o’clock, and was duly presented by the Secretary of State. The President received the Prince with marked courtesy, and welcomed him to the country in a few simple but hearty words of compliment. Without seeking, he said, to attach to this flattering visit of one so closely allied to the French throne, at this solemn crisis of the country’s history, an undue importance, he could but feel that his presence at the capital was a guarantee of the friendly interest and generous sympathy of the French Government. The Prince, it is reported, listened with deep interest to the informal address of the President, and replied with brevity and much feeling.”

One of Plon Plon’s aides, Camille Ferri-Pisani, however gave the strikingly different version of the encounter, noting in his Lettres sur les Etats-Unis, how the Prince – accustomed to a certain reception – had been forced to wait for fifteen minutes, with no ceremony and no major-domo or service staff on hand to tend to his needs (“You walk straight in, like in a café”, remarked the prince, clearly taken aback). Lincoln, apparently giving the impression that he was unused to receiving royalty and disastrously informed as to his visitor’s identity, inquired after the prince’s father, “Lucien”. A furious Plon-Plon sat in stony silence whilst Lincoln (“a good man, but without class nor much knowledge,” the prince is said to have noted sniffily), by now alerted to his faux-pas, attempted to engage the prince in small-talk about the weather. To finish the embarrassing scene, Lincoln took refuge in a long ceremony of shaking hands (seven men on the American side, two on the French), thus allowing the meeting to reach the appropriate length of ten minutes.

The afternoon was spent strolling around Washington in the company of William Henry Seward, American Secretary of State, before attending a grand dinner held by Lincoln. Dining in the company of senators, members of congress, two high-ranking Union military men – Major General George McClellan and Major General Scott – as well as the British representative, Lord Lyons, the evening was not without embarrassment, notably when the band organised by the Americans to welcome the French party struck up the Marseillaise, a song banned in France since 1852. In comparison to the earlier meeting, however, the dinner can be termed a success.

In the days that followed, the party made a one-day visit to George Washington’s home in Mount Vernon (6 August). They returned to Washington the same day.

Expressing a desire to see the Confederate side of the war, the party – issued with a pass and accompanied by soldiers bearing the white flag – journeyed across the Potomac on 8 August to Fairfax, Virginia, where the prince met J.E.B. Stuart, then a colonel in the Confederate army. Their next stop (on the same day) was Manassas, where Generals Johnston and Pierre de Beauregard – of French, via Louisiana, origins – were waiting. Although the party was received with respect and courtesy by both sides, Unionist and Confederate alike, Camille Ferri-Pisani lamneted the fact that the American generals seemed disinclined to recognise the prestige that the French considered integral to military command. Clearly surprised by a “frugality and coarseness [entirely in keeping] with American custom,” Ferri-Pisani describes how the lifestyle of a commanding officer on campaign differed little from the conditions experienced by the common soldier, and as a result encouraged a “shocking” lack of ceremony.

On 9 August, the Prince and his retinue were taken to view the site of the First Battle of Bull Run (21 July, 1861), a recent Union defeat and the first and-based battle of the Civil War. They returned to Washington the same day and without stopping carried on to New York.

On 16 August – the day after a grand dinner held onboard Jerome-Napoleon to celebrate the Saint-Napoléon – the party left New York and took the railroad west, visiting a selection of the Great Lakes – Superior, Huron, Erie – and surrounding cities, including Chicago and Cleveland, “one of the most pretty towns in the United States”. The party rejoined Clotilde and her companions at Niagara Falls. On 11 September, they crossed the American-Canadian border, and made a triumphant entry into Montreal. A similarly positive, pro-French reaction awaited the prince and his party in Quebec City on 13 September, although the prince interpreted this more as a “sentimental souvenir” and a reaction “against Britain” (the Canadian confederation would follow a few years later, in 1867) than any real desire to see a return of New France.

On 18 September, the party was back in New York and on 22 September, they arrived in Boston, the most “European city” in America, according to Ferri-Pisani, and high on the list of cities to visit for Plon-Plon. He visited Harvard university with the express intention of meeting the Swiss scientist, Louis Agassiz, one of the most illustrious geologists of the time, and well-known for his studies on glaciers and his theories on the ice age.

On 25 September, the last day of the prince’s trip, the French party was invited to a grand leaving dinner, held by the city of Boston and attended by the cream of New England society, including the Governor of Massachussets, senators, Agassiz and the Harvard president, Cornelius Conway Felton. That same evening, the prince and his companions boarded the Jerome-Napoleon and the steamboat set sail for Europe.