The imperial residence in Portoferraio on the island of Elba, I Mulini, is the only Napoleonic residence in the world where Napoleon, Emperor, lived uninterruptedly for ten months. Notwithstanding this remarkable fact and the presence of about 200,000 visitors annually, the complex of Napoleonic structures (which also includes the country villa of San Martino) has never received the attention it deserved within the context of the other Napoleonic palaces in Europe.

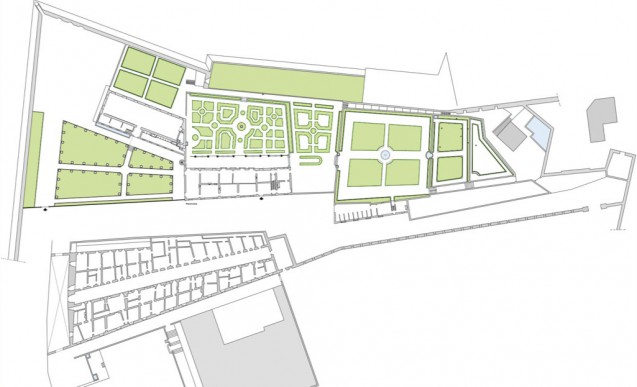

(Image caption: Plan of Portoferraio. The green line marks out the fortified area within which stood the Napoleonic complex of buildings, which in addition to I Mulini comprised the theatre, the kitches, the gardens, the stables, the forts Stella and Falcone and the temporary Pavillons where the Imperial Household was lodged. More information on this map.)

Whilst this state of affairs arose for many different reasons, the net result has been one of disappointment for visitors to the site, who have not been able to see Napoleon in the reality of the site, and worse still, lack of interest on the part of scholars, who abandoned study of Elban episode altogether.

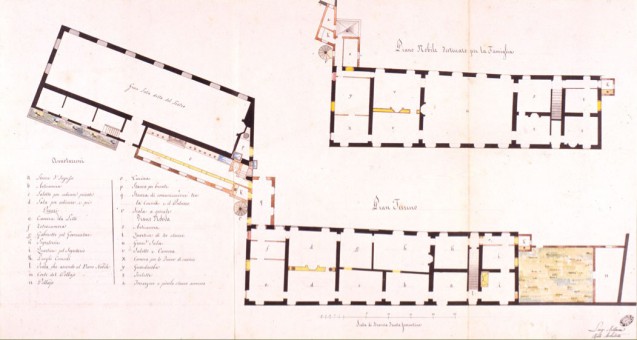

(Image caption: Graphic reconstruction of the central part of the I Mulini complex at the moment of Napoleon's departure from the island of Elba, 26 February, 1815.)

The decline of I Mulini began almost immediately after the Emperor's departure on 26 February, 1815, when the site was handed over (as it turned out, for the next 112 years) initially to the Grand Ducal government and later Italian State domains for military use. When the complex was ceded to the Italian Ministry of Culture in 1927, very few of its Napoleonic characteristics remained, whether internal, external, or indeed the relationships between the outlying buildings.

The decline of I Mulini began almost immediately after the Emperor's departure on 26 February, 1815, when the site was handed over (as it turned out, for the next 112 years) initially to the Grand Ducal government and later Italian State domains for military use. When the complex was ceded to the Italian Ministry of Culture in 1927, very few of its Napoleonic characteristics remained, whether internal, external, or indeed the relationships between the outlying buildings.

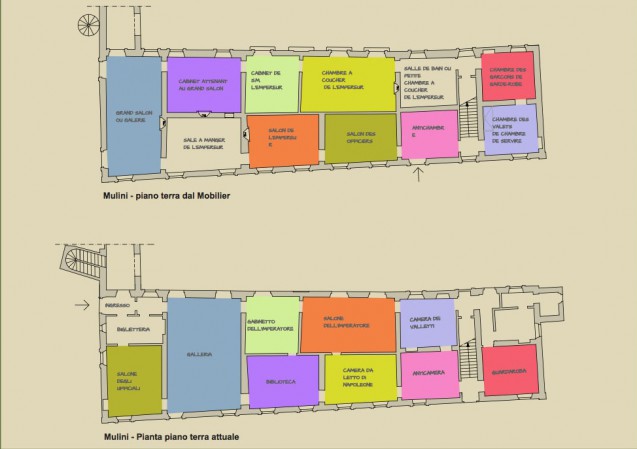

(Image caption: A comparison between the previous arrangement of the rooms in I Mulini and that currently exhibited as of 2013 after the philological research. Each colour shading indicates the use of the room and the previous serious interpretative errors.)

The governor in 1816, Strassoldo, was to modify the internal spaces significantly, adapting them to his own needs both as governor and as resident with his family, turning Napoleon's private apartment facing the garden into a secretary's office and a study, linking the latter to the private audience hall and the antichamber. The Galerie facing the garden leading towards the Grande salle du Bal was to be brutally divided into three spaces: a corridor, an antechamber and a bed chamber. This final operation – along with the displacement and enclosure of the external spiral staircase which originally connected the Galerie on the ground floor with the Emperor's chamber on the first floor, a solution which Napoleon had chosen also for his residence in Fontainebleau – was to weigh heavily on later interpretations of the original state of the Palais Impérial des Mulini. In the end, during the first half of the 19th century, the complex of buildings was to be divided into three lots, and this operation included the moving of the main entrance on the west façade of I Mulini and the erection of a wall separating the residence from the rest of the complex.

The governor in 1816, Strassoldo, was to modify the internal spaces significantly, adapting them to his own needs both as governor and as resident with his family, turning Napoleon's private apartment facing the garden into a secretary's office and a study, linking the latter to the private audience hall and the antichamber. The Galerie facing the garden leading towards the Grande salle du Bal was to be brutally divided into three spaces: a corridor, an antechamber and a bed chamber. This final operation – along with the displacement and enclosure of the external spiral staircase which originally connected the Galerie on the ground floor with the Emperor's chamber on the first floor, a solution which Napoleon had chosen also for his residence in Fontainebleau – was to weigh heavily on later interpretations of the original state of the Palais Impérial des Mulini. In the end, during the first half of the 19th century, the complex of buildings was to be divided into three lots, and this operation included the moving of the main entrance on the west façade of I Mulini and the erection of a wall separating the residence from the rest of the complex.

And despite the survival of a vast corpus of memoires, letters, historical plans and period documents bearing witness to the original state, these historical sources led an independent, parallel existence along side the reality of the building, which was to organised “as best as possible”. Given the almost complete absence of original furnishings and an “imaginative” and “ambitious” reconstruction of the interior spaces by one particular curator in the early 1950s, I Mulini was no longer in any state to transmit to a visitor even the vaguest idea of what this Emperor's residence had once been like.

(Image caption: Project by the architect Luigi Bettarini, executed after a commission from the Governor Strassoldo in April 1816. The demolitions are shown in yellow, the new constructions are shown in red. This plan was used as the basis for the philological reconstruction of the floor plan, making it possible to identify with accuracy the original Napoleonic use of the room in question.)

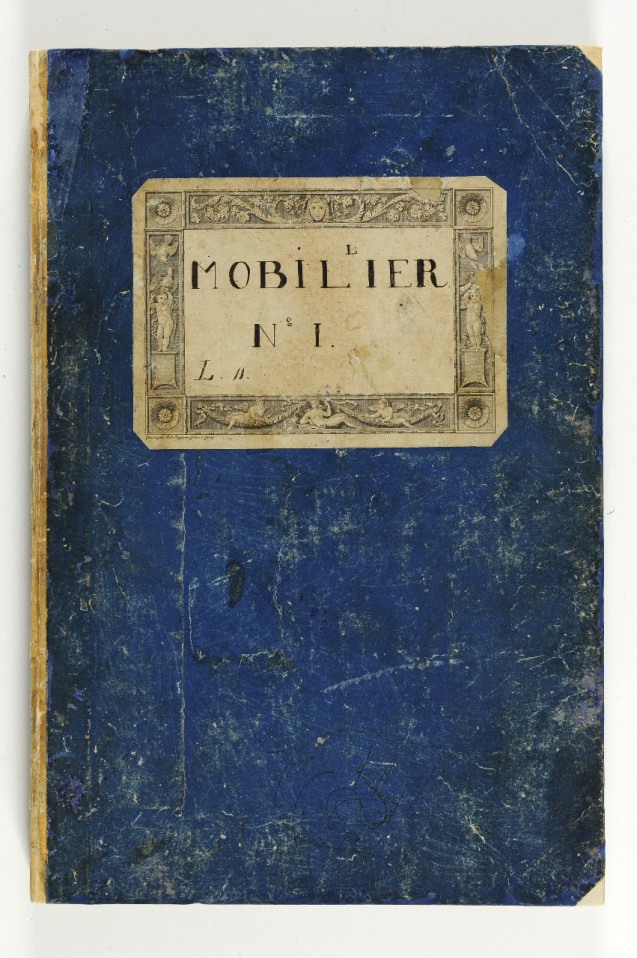

Our work has been based on research that has voluntarily ignored the approximate and superficial accounts of Napoleon on Elba, accounts which paid no attention to the only two fundamental sources which give a true picture of how the emperor's life was structured on the island, namely the Maison de l'Empereur and the Etiquette imperiale. Since Napoleon built life in his palaces (whether in Paris or on Elba) on these two ‘edifices', they are the only two sources which can provide sure information. Indeed, the only difference between Paris and Elba was the dimensions of the spaces in which Napoleon lived and worked, everything else, the hierarchy of the spaces, the organization of the Household and of his court, remained identical. A scale model, but nevertheless tout comme à Paris was how specialist Bernard Chevallier and principal supporter of the project, always described the palace on Elba, beginning with his introduction to the inventory of house possessions drawn up in October 1814 and published under the title Mobilier in 2005. In fact, the inventory has been bedrock of all the research related to the re-establishing of the Napoleonic state of I Mulini, research that has been generously funded by the Fondazione di Livorno.

Our work has been based on research that has voluntarily ignored the approximate and superficial accounts of Napoleon on Elba, accounts which paid no attention to the only two fundamental sources which give a true picture of how the emperor's life was structured on the island, namely the Maison de l'Empereur and the Etiquette imperiale. Since Napoleon built life in his palaces (whether in Paris or on Elba) on these two ‘edifices', they are the only two sources which can provide sure information. Indeed, the only difference between Paris and Elba was the dimensions of the spaces in which Napoleon lived and worked, everything else, the hierarchy of the spaces, the organization of the Household and of his court, remained identical. A scale model, but nevertheless tout comme à Paris was how specialist Bernard Chevallier and principal supporter of the project, always described the palace on Elba, beginning with his introduction to the inventory of house possessions drawn up in October 1814 and published under the title Mobilier in 2005. In fact, the inventory has been bedrock of all the research related to the re-establishing of the Napoleonic state of I Mulini, research that has been generously funded by the Fondazione di Livorno.

Our work has brought Napoleon back to his residences and returned the residences to Napoleon. In the words of the Italian Napoelonic scholar, Luigi Mascilli Migliorini: “Here, in the Villa dei Mulini, as under the tent at Austerlitz and in the salons at the Tuileries palace, [once again] we can understand the age-old message: wherever the Emperor is, there is the Empire”.

(Image caption: The Mobilier, the inventory which Napoleon had Pierre Deschamps, Palace Prefect, draw up in October 1814 for the imperial residence at I Mulini. In it, we find a room-by-room description of the types of furniture, colours of the furnishings, the wall coverings and even the objects on the tables and the different table games, including the provenance of the individual objects. Also see the Press Conference regarding the New furnishings for the National Museums of the Napoleonic Residences on Elba, 2010.)

Roberta Martinelli and Velia Gini Bartoli

Translation by Peter Hicks, November 2013.