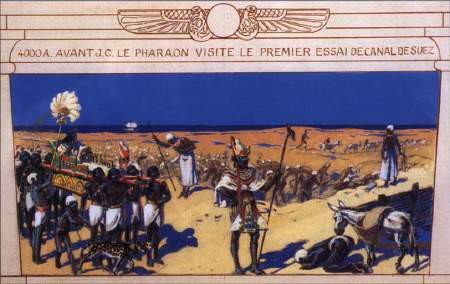

The first canal joining the Red Sea to the Nile and from there, via the Eastern branch of the so-called Pelusian river, to the Mediterranean, was dug around 2,000 B.C. on the orders of Pharaoh Ramses I. It was a mediocre work allowing the passage of light sail boats, either pulled along by horses or camels or rowed.

It was later improved a little by the Pharaohs Necho II (617-601 B.C.) and Ptolemy I, and then by Darius, King of the Persians, who occupied Egypt for a time. This is why it was nicknamed the Canal of the Four Kings. But, as it was badly kept up, it soon dried out and was silted up by the sand constantly swept around by the great desert winds.

In the 18th century, re-opening the canal was considered but the idea was soon abandoned because there was thought to be a significant difference between the levels of the Red and Mediterranean Seas which would require the construction of large and costly locks.

During his Egyptian expedition, Bonaparte himself rediscovered the remains of the ancient canal of the pharaohs near Suez and ordered Gratien Le Père to study the problem. On 24 August, 1803, he submitted an important Report on the linking of the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean via the Red Sea and the Suez isthmus . The route planned kept very close to the pharaonic canal. However, from the Nile, it went towards Alexandria (not along the Peluse, the Eastern fork of the river) and crossed the whole of the delta; it would thus have upset the region’s water system and made the project more than 400 km long. Moreover, Le Père estimated the difference in level between the two seas as being nearly 10 metres, something which Fourier and Laplace formally contested.

The Egyptian Pasha, Mohammed-Ali, absolute ruler of the country from 1811 to 1848, showed little interest in the project. After the death of Napoleon on Saint Helena, the Saint Simonian director of the project, Prosper Enfantin, approached the problem again in Egypt but the Pasha declared himself even against the route by the French engineer, Paulin Talabot, manager of the PLM railway, which for the most part followed Le Père’s route. Obviously, nothing could be undertaken which was against the wishes of Mohammed-Ali.

Nonetheless, two French engineers in the Pasha’s service, A. Linant de Bellefonds and Mougel, discreetly planned out a direct line from Suez to Peluse, crossing Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lakes, totalling 147Km in length. For his part, Bourdaloue, another French engineer, established that the difference in levels between the two seas was no more than 80cm (i.e. negligible) then Linant de Bellefonds also looked at the problem and confirmed his compatriot’s calculations.

Such, then, were the events and technical considerations of the 1840-1850 period.

Ferdinand de Lesseps’ great dream

There was nothing to show that the canal would one day be built until the arrival of the young French diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps, grandson, son, nephew and brother of diplomats, born of a family of Basque origins with a taste for adventure.

The Gods had obviously smiled on him when he was born: he was strong, handsome, intelligent, brave, tenacious, objective, patient when necessary, and both impulsive and reflective; a man of ability, ready for action. Moreover, he had great personal charm ¬ for example, even at the late age of 50 de Lesseps was still able to work his magic on Renan. A good horseman, he could not but please the Arabs, lovers of horses and fine horsemanship. To cap it all, he was the first cousin of Countess Montijo, mother of Eugénie, future French Empress.

Furthermore, his father, Mathieu de Lesseps, representing France in Egypt just after Bonaparte’s expedition there, intelligently foresaw that the modest chief of a thousand Albanian Janissaries, named Mohammed-Ali, possessed the qualities required for putting the Nile Valley back into order. Matthieu therefore discretely encouraged and helped Mohammed-Ali through his difficult start.

Then Ferdinand de Lesseps, in his turn, went to manage the French Consulate in Alexandria and soon distinguished himself for his courage during the plague of 1834-35.

The memory of his father and Ferdinand’s own distinguished action in difficult circumstances made him worthy of Mohammed-Ali’s approval. Mohammed-Ali put de Lesseps in charge of the education (both intellectually and in character) of Said his son and shaking the apathy out of him. Because Said, though intelligent, was corpulent and indolent, Ferdinand made him follow a strict regime of sport and put him on a horse whenever possible. But if failure loomed de Lesseps was always ready to give Said a plate of macaroni.

From his arrival in Egypt, de Lesseps studied everything to do with the Suez canal. He had many discussions with Linant de Bellefonds and promised to make this great work happen as soon as the opportunity presented itself. But he had to go back to France before he had the chance of doing anything. And the years went by…

In 1854, after he had left the diplomatic service, he learnt that his pupil and friend, Said had suddenly taken power in Egypt following the assassination of his uncle Abbas.

Ferdinand de Lesseps seized the much-awaited opportunity, rushed to Egypt in October 1854, reached the new Pasha on 15 November in the middle of a military expedition and presented him with his project for the digging of the Suez isthmus, which was that of Linant de Bellefonds. A fortnight later, he got the firman giving him the exclusive rights to set up the Compagnie Universelle du canal maritime de Suez, to use the canal and to construct a port at each end of it. The concession was for 99 years starting from the day the work started. At the end of this period, and failing any other agreements, the canal would become the property of the Egyptian government.

A second, more detailed, text was signed on 5 January 1856. It stipulated that the canal, a neutral waterway, should always be open to all merchant ships, regardless of nationality, in exchange for a transit fee. It was absolute equality for all. The company’s capital was set at 200 million gold francs divided into 400,000 shares at 500 francs per share. In December 1858, the Compagnie Universelle du canal was definitively established.

The share subscription was an unprecedented success. In France, 21,229 people, often of modest means, bought 207,111 shares. 96,517 went to Ottoman Empire nationals, the largest share going to the Pasha of Egypt. Buyers were found from all over Europe but the 85,506 share that Ferdinand de Lesseps had reserved for Austria, Great Britain, Russia and the United States of America did not find buyers. They were later bought by Said at Napoleon III’s instigation.

The signing of the concession firman and the closure of subscriptions at the end of December 1858, provoked much annoyance within the British government and the London Press. Great Britain’s official stance, which public opinion largely backed, was the fear that French influence over Egypt was growing and threatening Great Britain’s dominions in India. So it did everything in its power to revoke the firman, either going through the Pasha of Egypt himself or (for preference) his suzerain, the Ottoman Sultan. The Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, headed the campaign against Ferdinand de Lessep’s project himself.

The Turks were very embarrassed. They are by nature hostile to change and the canal was a change… and a big one! They were also wary of anything that could reinforce the strength of their uncomfortable vassal, Cairo. So they were sensitive to Britain’s arguments, especially when encouraged by timely and discreet gifts. However, they also feared the reaction of the French, their efficient allies during the Crimean war. They therefore resolved not to do anything. They thus hedged ¬ an art in which they excel.

As far as Napoleon was concerned, there was not a shadow of doubt that he was in favour of de Lesseps’ project. Whilst a prisoner in Ham, he wrote a short leaflet on the Nicaragua canal. He had, for a long time, been convinced of the pressing need to make maritime and land transport quicker, and therefore cheaper. He also foresaw that transport would have to grow enormously to meet the needs of international commerce.

But he knew Great Britain well and did not underestimate the danger of her hostility. He did not want to risk failure by engaging himself for too long a period or by moving too fast for the sake of the canal and then compromising other big projects he had in mind, such as the independence and unity of Northern Italy (then occupied by Austria), the consequent re-attachment of Savoy and the County of Nice to France, and the prickly question of the Lebanon.

He knew he had nothing to hope for from the old nobility with their memories of youth and the Napoleonic wars; but they would not be there long. In the meantime, a new leading class of industrialist, bankers, business men and wealthy tradesmen was coming to the fore. They wanted peace and security for their prosperity. Patience was required; but that this was part of Napoleon’s nature.

From 1855, Napoleon III showered Ferdinand de Lesseps with advice on prudence at the same time as encouraging him to persevere, because the more advanced the work was, the more difficult it would be to stop.

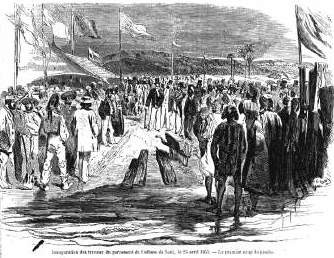

(Le Monde illustré)

After the banquet held in Paris, in April 1856, for the plenipotentiaries of the Peace Congress, the vizier, upon instructions from his Master, the Sultan, asked the Emperor what he thought of the canal. He said what he really thought: that he was very interested in the business; that it was something useful for everybody; that it had caused some opposition, especially in Great Britain, but he did not think this was grounded; and that trusting in the happy alliance uniting their two nations, he would leave it to the future to separate them. He then called for the English plenipotentiary, Lord Clarendon, to be summoned immediately and be informed of his stand.

Comforted by tangible signs of interest, Ferdinand de Lesseps hurried on the preparations. Thus, the first blow of the pickaxe starting the work on the canal was struck near Peluse on Easter Monday, 25 April 1859.

The highs and lows

The news of the start of work on the canal made Palmerston furious. He was all the more violently hostile towards the Frenchman because the latter had undertaken two long trips in the English counties to demonstrate to the Chambers of Commerce the benefits their members would reap from the digging of the Suez isthmus, and because his rival, William Gladstone, leader of the Whigs, sided with de Lesseps. In private, Palmerston considered de Lesseps a rogue and a crook. He was no more complimentary in the Commons, «I do not think,» he said one day in 1857 «I was mistaken in saying that the project is one of those pipe dreams so often created to make British capitalists separate themselves from their money with the result that they are left definitively poorer whilst making others richer».

Ignoring these insinuations, Ferdinand de Lesseps continued proclaiming that no country would benefit more from the canal than Great Britain. This was said at the time of the serious revolt of the Sepoys in the India (1857-1859) and the Russian invasion of Asia, proving London’s interest in having a fast waterway through which to quickly send troops and equipment to the Far East without having to make the long detour around the Cape of Good Hope.

Under Palmerston’s orders, the Ambassador in Constantinople, Sir Henry Lytton Bulwer, was so insistent that Mouktar bey, the Turkish Minister of Finance, went to Alexandria at the beginning of October 1859 with a warning letter from the Sultan requiring an immediate halt to the work.

It was a very upset Viceroy Said Pasha, strong believer in the canal, who called a meeting of the foreign consuls to inform them of his intention to obey. To the amazement of everyone, the Consul General of France, Sabatier, highly approved this action and ordered the French nationals of the Compagnie Universelle to stop work.

Ferdinand de Lesseps immediately made an appeal against this decision to Napoleon III who received him in Saint Cloud on 23 October 1859, and assured him of his support, though still discreetly. Sabatier, relieved of his functions, took his retirement together with a golden handshake. Instructions were sent to the French Ambassador in Constantinople, Mr Thouvenel, supported by the Baron of Prokesch for Austria, Prince Lobanoff for Russia and Mr de Souza for Spain. The Turks were not asked to change their minds but just to close their eyes to the continuation of the work. They were happy to become deaf, dumb and blind rather than have to take sides. Thus, de Lesseps was now free to act. On 18 November 1862, the waters of the Mediterranean reached Lake Timsah which had nearly always been dry before then.

Since this obviously did not conclude matters for Sir Henry Lytton Bulwer, he did not surrender. Bulwer still feared that the French would become permanently established in Egypt, that the canal was, above all, a defence protecting the country from invasion by the Turkish army and, finally, that the Egyptian workers in the company, who would be well paid, well treated and used to European discipline, would form a reserve army for Egypt, ready to invade Palestine, Syria and the Lebanon, as had happened between 1832 and 1840.

The death of the Viceroy Pasha Said on 18 January, 1863, gave the English diplomat a timely opportunity to create more difficulties.

The new Viceroy, Ismail Pasha, whose culture was Western and, more particularly, French, was not as reliable as his late uncle.

He was a weak man. You could see the beginning of nationalism in him. Upon taking power, he declared, «No-one is more pro-canal than me but I want the canal to belong to Egypt and not Egypt to the canal.». With that, he meant to show Ferdinand de Lesseps who was boss.

His Foreign Affairs Minister, Nubar Pasha, a Christian Armenian and an ingenious and wily fellow, had been subtly playing the English game since a trip to London in 1850. As de Lesseps had, up until now, got his strength from his good relations with the Egyptian Government, Nubar Pasha now attempted to create conflict between them which would lead to the ruin of both de Lesseps and the Compagnie Universelle.

Nubar Pasha, the grand vizier Ali Pasha and Sir Henry Bulwer Lytton came up with the following ultimatum which was sent to the Viceroy by Turkey on 6 April, 1863:

– a halt to forced labour for digging the canal together with a reduction in the number of workers from 20,000 to 6,000, the latter being volunteers;

– retrocedence to Egypt of land given to the Compagnie Universelle;

– revision of the size of the canal so as to make it less wide and reduce its efficiency as an obstacle to possible action by the Turkish Army.

At the same time, the Viceroy Ismail dissociated himself from the Company and Nubar Pasha went to Paris on an anti-de Lesseps campaign. He had already noticed that three French lawyers, the Republicans Jules Favre, Jules Dufaure and Odilon Barrot, had pronounced themselves against the legal validity of the Compagnie Universelle’s position. He got in touch with the Duke of Morny who listened to him and sympathised with his views. De Lesseps, alerted to this, dared say to the latter that angry rumours were running around about his strange role in this business. With the support of the Empress and Prince Napoleon Jerome, de Lesseps gained Napoleon III‘s official approval, and the Emperor told Morny not to meddle in the canal issue anymore.

The Viceroy Ismail and Nubar Pasha were worried by these unforeseen rumours and, backing down, requested the arbitration of the Emperor of the French (as suggested by Prince Napoleon Jerome) in the conflict between Egypt and the Compagnie Universelle. The sentence given on 6 July, 1864, can be summed up as follows:

The Compagnie Universelle was to receive 84 million gold francs and keep 10,864 hectares which were indispensable to its requirements. Egypt accepted. Turkey did not say a word and so consented. The Compagnie Universelle was to obey the Turkish-Egyptian order to suppress forced labour, give back to Egypt the fresh water canal feeding the Suez isthmus work sites and surrender the 60,000 hectares of irrigable land. Palmerston was furious but could do nothing as public opinion in his country had started changing since the signature, in 1860, of the free trade agreements between England and France. Gladstone openly mocked his «hydrophobia» of the Red Sea.

Thus the work continued but now in a new climate of calm and French ingenuity soon brought powerful machines to replace the men .

Then Palmerston died in 1865 and all problems disappeared. On 19 March, 1866, a firman from the Sultan Abdul-Aziz finally ratified the agreements made between the Viceroy Said and de Lesseps. The latter was congratulated in England where there had been a complete turnaround in public opinion. After visiting the canal works, the Prince of Wales, future Edward VII, judged Palmerston of being «guilty of an appalling error of judgement».

But in 1867, the money ran out: the mechanisation of the work had been very expensive. Once again, Napoleon III intervened discreetly by having a quiet word with the Legislative Body and the Senate which then authorised the giving of a loan of 100 million gold francs in lots to the Compagnie Universelle, to be covered in a few days.

The project and the work on the Suez Canal was presented in the Egyptian Section of the Universal Exhibition, in Paris, in 1867.

On 15 August, 1869, the waters of the Mediterranean finally flowed into the Red Sea via the Bitter Lakes. The maritime canal from Suez to Port Said, passing a little West of the Peluse, was 164Km long, 54Km wide and 8m deep. 75 million m3 of debris had been extracted, 3 towns founded (Suez, Ismailia and Port Said), 2 ports created (Suez and Port Said), and millions of hectares were now covered with rich farmland thanks to the fresh water canal. It cost Frf 432,807,882. Enthusiasm for it was as great in Great Britain as it was in France. Russia too was pleased. The US, however, owing to its geographic position, felt only marginally interested in the event.

The excellent relationship between Napoleon III and de Lesseps, the Sovereign’s ability, patience and knowledge of the Britons, and his partner’s tenacity triumphed over all the difficulties.

The Khedive Ismail asked Empress Eugénie to inaugurate the canal ¬ an apt tribute to France. After being received in Constantinople by the Sultan Abdul-Aziz, she continued on to Port Said on board the imperial yacht, the «Aigle», arriving there on 16 November, 1869. She was greeted with gun salutes from the war ships which had come from all over the world. The Khedive, the Austrian Emperor, the Prince Royal of Prussia, the Prince of the Netherlands, the Prince of Hanover and the Ambassadors of Great Britain and Russia went to greet her.

On 17 November, the Aigle was the first vessel to enter the canal, followed by an impressive cortege of about 40 war and merchant ships. In the evening, they dropped anchor at Ismailia on Lake Timsah. On 19 November, they reached the Bitter Lakes and on 20th, the flotilla came out at Suez into the Red Sea.

They returned to Port Said on 21 November, in a single day’s journey, as easily as they had travelled out. The culmination of all the work was successful in every sense and there was a joyful celebration of «the marriage, on the canal, of East and West».

Napoleon III wanted to make de Lesseps Duke of Suez but he declined the honour.

On 23 April, 1884, at the French Academy, Ernest Renan received Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had by then been elected to the Henri Martin chair. As perspicacious as ever, Renan spoke the following prophetic words to de Lesseps à propos the canal, «You, Sir, have thus marked the spot of great battles of the future …»