The Power of the Satirical Song

Any discussion of these matters must begin with the (much-feared) political song. Satirical ditties were carefully controlled during the Empire period. In February 1809, close to the high point of the Empire, it is reported that Napoleon remarked to Roederer (a close political companion since the beginning): “It used to be said that France was a monarchy tempered by songs. We cannot allow things and people to be the subject of songs today”,[1] and a directive almost two years later (28 December 1810) noted that “informal woodcutter printers (‘imagiers’) or playing card printers (‘dominotiers’) could not print texts or songs below their images suitable for peddling (things that would have been subject to examination had they come out of a formal printer’s press) unless such texts/image combinations had been submitted for previous examination”.[2] The result of this censorship was that only songs from the 1814s and 1815s could afford to be critical. Given the coincidence of the debacle in Russia with the end of the Empire, a great deal of this kind of musical production survives, sometimes mocking, sometimes sad.

One example is the song, Danse sans violon, published in Neuchâtel in 1814. It deals sarcastically with the campaign thus:

“To Moscow, you came on a visit,

Alexander has returned the compliment,

Saying to you, “Now we’re square”.

Now, Napoleon, it’s time

For you to dance without a violin, din don”[3]

The image here of “dancing without a violin” has two implications. First, the French expression ‘il est temps de danser’ implies Napoleon is being led a merry dance, and second, ‘danser sans violon’ implies a dance he’s forced to do, worse still without a violin, in other words without assistance. The song is all the more ironic in the light of Napoleon’s very famous words, recorded by Roederer in the same February 1809 conversation mentioned above: “I love power […] as a musician loves his violin”.[4]

Another song, also from the Vaud, is sadder (and not maliciously gleeful):

“An old soldier, sad and lost in his dreams,

Sang these words on the hard snow:

“Come, icy Winter, whirl your blizzards!

Hide our battalions from the enemy.”[5]

The song La Campagne de Russie (The Russian Campaign) here has caricatural or mocking lyrics written by Delmasse[6], and they were arranged to fit the well-known French melody (still sung today), “Compère Guilleri Titi Carabi”. It was common in the Napoleonic period for satirical words to be written to fit popular tunes. English caricatures of the Napoleonic period survive which do this (words mocking Napoleon were attached to the tune “Bluebells of Scotland” in an 1803 caricature, and the practice is alive and kicking on UK football terraces today). Here in France, the melody was accessible to contemporaries via Capelle’s 1811 compendium of tunes called Clé du Caveau, where it was published as no. 561.

- There was a little man, / called “The Great” / when he left. / Now, you’re going to see how / he came back small / to Paris.

(Chorus) Let’s be cheerful and gay, my friends, and sing of the fame / Of Napoleon the Great, / He is the hero (twice), a hero on a tiny scale.

- Running fast and out of breath, / he believed that capturing Moscow / was the big deal. / But this great captain, / by jingo, saw nothing / cos’ smoke got in his eyes… / (Refrain)

- What can you do in a city / whose only houses / are made of charcoal? / It would be difficult / to spend the winter there, / out in the open air. / (Refrain)

- Without asking for the change, / proud as a Caesar, / an accidental Caesar, I mean, / in this parlous state / Napoleon the Great / ran away. (Refrain)

- He abandoned his army, / leaving them without bread or a general. / It made no difference. / They were used / to eating horsemeat / as a special treat. (Refrain)

- Slipping away from of Russia / as swiftly / as the wind / His numb Majesty / fled incognito / in a sled. (Refrain)

- We are quite right to be surprised / that he did not deliberately proclaim / decrees / ordering the prolongation of autumn / and the abolition of ice / and freezing cold (Refrain)

- O, excellent campaign, / the decrees have been executed, / accomplished / The army is gone to perdition, / though you can’t say the same / for the brigand, (Refrain)[7]

In France, after the Emperor’s death in 1821, however, it does not seem that the Russian campaign and the year 1812 were a popular subject for composers. I could not, for example, find a song by Béranger dedicated to this subject. Béranger did compose a song entitled Les Deux Grenadiers (1822), but, unlike the famous Schumann/Heine song (1840) where the two grenadiers were recently released from their captivity in Russia, Béranger’s grenadiers are on the island of Elba.

Music and popular song in Russia

As far as instrumental music in Western Europe is concerned, apart from the two pieces I will discuss here, I do not get the impression that the retreat and the campaign was a source of great inspiration for classical composers. The results of my research at the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris were meagre; indeed I found only two works of substance. On the other hand, the situation in Russia is quite different, since 1812 was trumpeted as the great victorious Patriotic War. It is therefore not at all surprising that musical works on this theme were written by some leading composers. The Cossack, Alexander Aliabev, who had participated in the campaigns of 1812-1814, wrote romances on the theme of 1812 such as “The Hussard’s adieu”,”Bayan’s Song” and “The Song of the Old Man”. Dimitri Bortnianski, Ukrainian director of the Russian Imperial Chapel, set to music Zhukovsky’s poem titled “A Bard in the Camp of the Russian Warriors”, the last verses of which were written in October 1812. There were also triumphal marches, funeral marches and even Polish marches commemorating 1812, by composers such as P. Saltykov, John Field, P. Dolgorukov, O. Koslowski and G. Vysotskiy.[8] Also not to be forgotten are the Russian musical works commemorating the first centenary, including Astafieva’s cantatas “Borodino”, Chertkovoy’s “The song of Moscow in 1812”, Zabel’s “In the Shadow of the War Chief” and Bagrinowski’s opera “1812” (the libretto from Pushkin’s “Roslavlev” and Danilewski’s “Moscow Burning”) and 1812 by Janowskiy with a libretto by Mamontov.[9]

The best-known Russian works today are Sergei Prokofiev’s thirteen operatic tableaux entitled “War and Peace” (based on the novel by Tolstoy) and Tchaikovsky’s solemn overture, “1812”. For technical reasons (i. e., I do not speak Russian), I cannot approach Russian folk music. But there would appear to be a vast repertoire of such material. Already for “War and Peace”, Prokofiev was going to use Russian folk songs from the campaign period to act as the foundations for the choruses in the opera, and Tchaikovsky had the same idea when he asked his publisher Jurgenson for a copy of the S. I. Ponomareva’s “Moscow in native poetry”. An example of a Russian popular song on the subject of 1812 (which bewails the ruin of Moscow) was published in French translation by Chuquet in his volumes entitled Guerre de Russie, volume 2,[10] as follows in English translation of the French (unfortunately without melody):

“It has been destroyed, my beloved road,

The road that goes from Mojaisk to Moscow.

The enemy followed this route,

My beloved road is soaked in blood,

Alas! soaked in blood.

The enemy went all the way to Moscow.

It is in ruins, the city with its white walls,

It has been consumed by fire.”

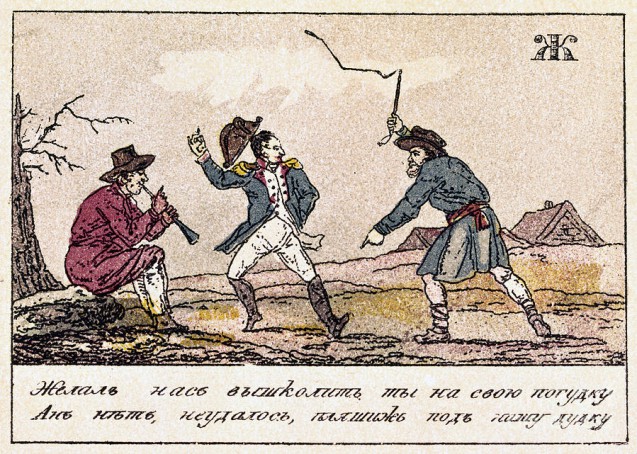

Marie-Pierre Rey recounts how these Russian popular songs, often accompanied by Lubki (small, brightly coloured engravings bearing scenes or illustrating tales), bolstered popular appetite for a patriotic and national war.[11]

Music published in France recalling 1812

It is perhaps remarkable that pieces reminiscent of the disaster of the 1812 campaign were published in France. And yet such is the case. The two works here in question on this subject were composed in close chronological proximity to the Empires. These are The Fire of Moscow by the Prussian composer Daniel Steibelt and Alphonse Leduc’s “Historical Quadrille” of the same title, both diametrically opposed in style and treatment. The Prussian’s composition highlights Napoleon’s suffering and defeat. For Alphonse Leduc and his literary collaborator, Napoleon Crével de Charlemagne, the emphasis is on the treachery of Russia and the fatal destiny of the Emperor.

Daniel Gottlieb Steibelt (who was born in Berlin in 1764 and died in St Petersburg in 1823), was a virtuoso pianist, “en vogue” in Paris “for his brilliant or humorous compositions”, to quote Johann Friedrich Reichardt in 1803. [12] Steibelt was to play for the Emperor at a concert in an Imperial residence on 30 April 1807. For his performances, he received the usual fee of 1,200 frs. On the other hand, he was far from being one of the best earners in the Imperial era. Two days later, Mrs Paër received 6,000 francs for the same type of performance.[13] Virtuoso though he may have been, he was neither historian nor too concerned about his political connections, provided he received his fee. Thus he wrote (without shame) for Marie-Antoinette (the sonata la Coquette is dedicated to her), for the British Admiral Duncan (who got a programmatic work The Battle of Camperduin in 1797), for Josephine (an opus 45 sonata dedicated to her in 1800), for Napoleon himself (Gran Marcia di Buonaparte in Italia, 1801) and finally The Fire of Moscow, dedicated to “Prussians reborn after 1815” in the edition printed in Prussia but without dedication in France. This work was also published by Potz in Moscow in 1814 with the subtitle “Fantasie for Forte Piano” where it was dedicated “to the Russians”.[14] In addition to his lack of concern for political credibility, Steibelt’s reputation was ‘mixed’ (to put it mildly), especially in German-speaking countries. The Dictionary of Prussians, published at the beginning of the 20th century, did not pull its punches: “There was a time when there lay on every piano, next to Pleyel’s beloved works, one or two of the popular Prussian composer, Daniel Steibelt. Only very rarely did one find scores by Mozart, Haydn, or Beethoven. But the destiny of everything that is superficial and contentless is rarely unjust, hence today [that is, at the beginning of the 20th century, ed.] one almost never finds piano compositions by Pleyel or Steibelt. And yet, his work was not simply null and void. Steibelt was a very prolific composer and a brilliant virtuoso. While, as is often the case with virtuosos, it did not vary and focused only on gimmicks and special effects, it was the subject of public wonder in all major cities, and particularly in the upper echelons of society, which rarely promote the best of art and more often the superficial. At the same time, contemporary critics of Steibelt’s playing praise his passion, his remarkable technique, the lightness of his touch and his elegance. But they also criticised his habit of always playing in the same way, never playing the Adagios, and his deliberate mannerisms in particular (his tremolo of the left hand – although, precisely this effect (it was said) could excite ladies so much as to make them to faint…). On top of all that, he had character flaws that made him unbearable. He was extraordinarily vain, arrogant and rude.” Steibelt spent the end of his career in Russia, and it was undoubtedly this fact which led to him choose the fire of Moscow as his subject. In 1808, he was invited to St Petersburg by the Emperor of Russia Alexander I and in 1811 he succeeded to Boïeldieu as director of the Imperial French opera in St Petersburg – though French opera went into steep decline when the Russian Campaign began. It was at this position that he lived in financial security until his death. With regard to the work The Fire of Moscow, the programmatic structure of the work probably indicates that it was destined for an amateur audience. Interestingly, he set to music the Tsar’s ‘national’ anthem. The melody is well known. It is the English song “God, save the King”. After 1812, this melody received words by the Russian poet Zhukovsky and was given the title The Prayer of the Russians. This melody was used in 1833 as a basis for the composition of the music of the Russian national anthem, which was called in the English manner “God save the tsar”.

No more than 40 years later, in 1846, another Fire of Moscow was all the rage. This time it was a Historical Quadrille (a quadrille was a piece for dancing), which dates from 1846, at the very end of Louis-Philippe’s reign. It was composed by Alphonse Leduc, the founding father of the famous music publishing house still in existence. The piece appeared four years after the foundation of the house at no. 78 in Passage Choiseul.[15] Alphonse was a skilled player of the bassoon, flute and guitar, and his works were numerous: 960 piano solos, 632 of which were in the form of dance, like the work here. These are 5 short movements written for piano (possibly accompanied by a pistoned cornet, a flute and a violin), called respectively ‘Battle of Moscowa’, ‘The French in Moscow’, ‘A party at the Kremlin’, ‘The conspiracy’, and ‘Fire’. It’s true that in the introduction there is a very serious historical text, but the music is strikingly ‘jolly’, belying the tragic nature of the ‘story’. Here we are no longer in the evocation of a contemporary history, but that of a history lost in the past, an episode which can become a source of entertainment.

War and Peace by Sergei Prokoviev

Prokoviev began writing War and Peace, opera in 13 tableaux at the end of 1940 just before the Nazi invasion of Soviet territories in June 1941 – he finished it in 1952 one year before his death. Although it was not this invasion that was the starting point of the opera, the entrance of the Nazi troops added to his foreboding and anxiety. Evacuated to the Caucasus in summer of ‘41 with many composers, artists and intellectuals, he settled in Tiblissi (Georgia) where he began to study (in addition to Tolstoy’s work) not only the stories of the 1812 campaign (in particular the account written by the poet Davidov), but also he will found a collection of anonymous songs of popular inspiration which arose spontaneously as a result of the meeting of the Tsar’s troops and Russian peasants of the 1812 period. Working with his second wife, Mira Mendelssohn, he managed to complete a first version of the opera in summer 42 (with only 11 tableaux). It was sent to the Committee of Cultural Affairs in Moscow for an official evaluation – Svjatoslav Richter and Alexandre Vedernikov played it before the committee in its piano duet form. Changes were called for to strengthen the patriotic side. Prokoviev followed suggestions, including the inclusion of a choral epigraph and a choir of the people during the scene of the French in Moscow (audio file) (Tableau 11 in the more complete version). Indeed, a choir of Muscovites sings as follows: “In the moonless night, friends, we will take the sacred oath never to see again our houses or our fathers […] until we have defeated the forces of Bonaparte,[…] before we are avenged…”. Prokoviev himself said: “This opera was conceived before the war, but this war has pushed me to complete it. Tolstoy’s great novel described Russia’s war against Napoleon, and at that time, as it is today, it was not a war between two armies, but between two peoples”. What was basically a complete score was played on 7, 9 and 11 June 1945 for the first time, in the room of the concert hall of the Moscow Conservatory, but true full-length public performances would never take place before the composer’s death because of official opposition. Indeed, Prokoviev had refused to compose a work of Stalin’s glory (despite the warnings of his entourage that he should not say “no”), and he refused to remove the tableaux that contained (according to the representatives of the USSR) “significant political weaknesses”, where the portrait of Napoleon was not harsh enough, and the staging of the fire was too “colourful” and devoid of any meaning. And indeed by persisting in sticking close to the spirit of the novel, he was included on Zdanov’s ‘blacklist’ in 1947. He was criticized for being a composer of “formalist and anti-popular” music. And the fact that opera was never actually performed during his lifetime was the tragedy of his life. He was later to say: “I am ready to accept the failure of any of my works, but if you knew how much I would like War and Peace finally to see the light”. The first truly integral performance, with the choir epigraph and without cuts, took place on 15 December 1959 at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow under the direction of A. Melik-Pashayev.

1812, the Solemn Overture by Piotr Illich Tchaikovsky

was composed by Piotr Illich Tchaikovsky in his religious (and depressive) period of the late 1870s and early 1880s.[16] It was commissioned by Nikolai Rubenstein, the friend and promoter of the Russian composer’s music, who had been appointed head of the music section for the 1881 Moscow exhibition of art and industry throughout Russia. Indeed, in May 1880, Nikolai had given Piotr three choices:[17] either a work for the inauguration of the 1881 exhibition (which was eventually cancelled and postponed to the following year), a work celebrating the twenty-five years of Tsar Alexander II’s reign, or a cantata for the inauguration of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. A month later, the commission was weighing heavily on the composer’s heart: music on commission irritated him, he was not inspired by the idea of a commemoration for the Tsar, and he hated the cathedral.[18] After the summer, he was still working, but judging from his correspondence this had become a work for orchestra with choir[19] since he asked his publisher for a copy of a collection of patriotic poetry by S. I. Ponomareva. Obviously he had made his choice of destination of the work because in his letters he speaks of “music for the exhibition”. And during the autumn and winter he worked on his opening for the inauguration of the exhibition, finishing it in November 1880. But the composer was not very proud of what he had done (and which he had felt compelled to complete out of love for his friend Rubenstein), classifying it as “very loud and noisy”, “without artistic merit”.[20] In 1882, he told his publisher Jurgenson: “I’m not sure if my Overture is good or bad, but it’s probably (without any false modesty) the latter”. In the course of 1881 he finished the versions for piano solo and piano duet, and the work inaugurated the exhibition on 8/20 August 1882 in a program of works entirely by Tchaikovsky in the great hall of the exhibition of all Russian art and industry in Moscow, the orchestra under the baton Ippolit Al’tani. On the other hand, the project to inaugurate the cathedral was never far from the compositional idea. The construction of this building had originated in a vow made by Tsar Alexander I on Christmas Day 1812 to thank God for the victory of 1812. Due to financial problems (the first architect A. Wittberg stole money from the project) and due to the abandoning of the “cathedral” project during the 1820s and its resumption in the 1830s, construction in the end stretched over 70 years, ending in 1883 with the official inauguration and dedication on 26 May. So, sometime after the inauguration of the exhibition in 1882 and up to (and including) 26 May 1883, the work eminently inspired by Alexander’s great patriotic victory finally granted the Tsar’s wish – accounts regarding a performance of the work in a tent outside the cathedral are difficult to corroborate. Come what may, the title page of the work informs us that the opening was written for the dedication ceremony of the cathedral, 26 May 1883; and not far chronologically from the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino.

But the life of the work was not over. In 1961, the opening was changed in the USSR. The theme “God save the Tsar” (Bozhe, Tsaria Khrani) by A. Lvov (now too tsarist) was replaced by the theme “Slav’sja” from a Glinka opera known in Soviet times as Ivan Susanin (a name acceptable to the Party since Ivan was a hero of the people who had fought against the Poles in 1612-13). However, the 1812 overture had the final laugh since the Communists had forgotten that the original title of Glinka’s opera had been “A life for the Tsar”!!

[1] My thanks to Prof. Alexander Mikaberidze, LSU at Shreveport and Maria Mnatsakanova, intern at the Fondation Napoléon March-May 2012, for their crucial help with the Russian sources. Quoted in G. D. Zimmermann, « Buonaparte ou est ta gloire ? » : ce que l’on chantait en Suisse romande à propos de Napoléon, entre 1793 et 1919, Neuchâtel: Zimmermann, 2005, p. 18, in Autour de Bonaparte. Journal du P. L. Roederer, Paris: Daragon, 1909, p. 256.

[2] Quoted in G. D. Zimmermann, « Buonaparte ou est ta gloire ? » cit., p. 19, « Boudon, 329-30 ».

[3] “A Moscou tu fis visite / Alexandre te la rend / En te disant / Quitte à quitte, / Napoléon il est temps / De danser sans violon din don”.

[4] Autour de Bonaparte. Journal du P. L. Roederer, Paris: Daragon, 1909, p. 246.

[5] “Un vétéran assis triste et rêveur / Chantait ainsi sur la neige durcie : / Allez frimas, volez en tourbillons ! / A l’ennemi cachez nos bataillons.”

[6] Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. 12 861.

[7] 1) Il était un p’tit homme / qu’on appelait le grand, / En partant, / Or, vous allez voir comme / Il revint un petit / A Paris. / (Refrain) Gai gai, mes amis, chantons le renom / Du grand Napoléon, / C’est le héros (bis) des petites maisons. 2) Courant à perdre haleine, / Croyant prendre Moscou,/ Ce grand coup, / Mais ce grand Capitaine / N’y a vu sarpejeu / Que de feu. (Refrain) 3) Que faire dans cette ville / Qui n’a plus de maisons / Qu’en charbon ? / Il serait difficile / D’y passer son hiver / En plein air. (Refrain) 4) Sans demander son reste / Fier comme un César / De hasard, / Dans cet état funeste, / Napoléon le Grand / Fout le camp. (Refrain) 5) Il laisse son armée / Sans pain sans général, / C’est égal, / Elle est accoutumée / A manger pour régal / Du cheval. (Refrain) 6) S’esquivant de Russie, / Aussi rapidement / Que le vent / Sa Majesté transie / S’enfuit incognito / En traîneau. (Refrain) 7) A bon droit, on s’étonne / Qu’il n’ait pas fait exprès / Des décrets, / Pour prolonger l’automne / En supprimant verglas / Et frimas (Refrain) 8) O campagne admirable, / Les décrets sont remplis / Accomplis, / Son armé est au diable, / Que n’en est-il autant / Du brigand. (Refrain).

[8] Marche à la mémoire de Koutousov, by P. Saltikov, 1813, Marche triomphale, by John Field devoted to the victories of Wittgenstein, Marche funèbre by P. Dolgoroukov, amateur composer who participated in the campaign, Polonaise sur la guerre de 1812, by O. Koslowski, choral work dedicated to the victories of Koutousov, saviour of the fatherland, based on a text by N. Nikolaiev, Marche triomphale consacré au retour de l’armée russe à la patrie, by G. Vysotskiy (after 1814).

[9] See Бородино 1812, [Borodino 1812] [Ed. Jilin P.A.]; Moscou: [Muicl], 1987, p. 313-15.

[10] A. Chuquet, 1812. La Guerre de Russie, Paris: Fontemoing, 1912, vol. 2, p. 359. Chuquet also cites 5 German songs (of negligible literary value) about the flight of Napoleon, ibid., pp. 361-366.

[11] See Marie-Pierre Rey, L’effroyable tragédie. Une nouvelle historie de la Campagne de Russie, Paris: Flammarion, 2012, pp. 208-210, and T.T. Aljavdina, « Jepoha otechestvennoj voiny i russkaja muzyka » (« The Era of the Great Patriotic War of 1812 and Russian Music »), in Jepoha 1812, issledovanija, istochniki, istoriografia, sbornik materialov (L’époque de 1812, études, sources, historiographie, recueil de documents), Moscow: Trudy Istoricheskogo Muzeja (Collection « Travaux du Musée historique), (3 tomes), tome 1, pp. 150-166.

[12] Johann Friedrich Reichardt, Un hiver sous le Consulat, « 11 janvier 1803 ».

[13] Henry Lecomte, Napoléon et le Monde Dramatique, p. 451.

[14] The Prussian edition has furthermore concluding victory dances, absent from the Paris edition. The title page of the Russian edition was published in Бородино 1812, [Borodino 1812] [ed. Jilin P.A.]; Moscow: [Muicl], 1987, p. 314. It furthermore bears the following French verses (also absent from the Paris edition): « Ce superbe ennemi des Princes de la Terre/ Contre eux, contre leurs droits, si fièrement armé,/ Tombe et meurt, foudroyé par la même tonnerre/ Qu’il avait allumé. Rousseau », de Jean-Baptiste Rousseau (1670-1741), Œuvres diverses de M. Rousseau, Nouvelle édition revue, corrigée et augmentée par lui-même, Tome 1, London: Aux de’pens de la compagnie, 1731, Odes, livre IV, no. 5, p. 179, « Au roi de Pologne ».

[15] Grove, Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 14, p. 457.

[16] See the website http://www.tchaikovsky-research.net/en/Works/Orchestral/TH049/index.htmlhestral/TH049/index.html, consulted February 2018, extract from Музыкальное наследие Чайковского (1958), pp. 295–297

[17] See the letter from Jurgenson to T. 29 May/10 June 1880 — Klin House-Museum Archive.

[18] Letter no. 1525 from T. to Jurgenson, 3/15 July 1880.

[19] Letter no. 1577 from T. to Jurgenson, 1/13 September 1880. The book, Москва в родной поэзии. Сборник под редакцией С. И. Понамарева (St Petersburg, 1880) remained in T.’s library and is today in the collection of the archive of the House Museum Klin. A version of the overture with choral parts exists. It was prepared in 1960 by the American conductor Igor Buketoff (1915-2001).

[20] Letter no. 1609 to Nadezhda von Meck, 8/20–10/22 October 1880.