Napoleon III’s reign was a period of great modernity and change in France and in Europe. With the increasing industrialization of France came greater interest in the life of the “worker”, and Europe saw the birth of the nations of Italy and of Germany. Here you can read about Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s early years, his coming to power, and other events during the Second Empire.

1808 – BIRTH OF LOUIS-NAPOLEON

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte was born in Paris on 20 April 1808. His father, Louis Bonaparte, was the brother of Napoleon I and his mother, Hortense de Beauharnais, was Napoleon’s step-daughter by his first marriage to Josephine. At this time, Napoleon was still without an heir and so intended to take Louis-Napoleon as the successor to the Imperial throne. Following the fall of the First Empire in 1815, Hortense moved to Arenenberg in Switzerland. Louis-Napoleon grew up with a strong sense of respect for his family history and origins and quickly became interested in politics, seeking to restore the Bonaparte dynasty to power.

Illustration: L. Ducis, Napoleon I after lunch, surrounded by the young princes and princesses of his family, on the terrace of Château de Saint-Cloud in 1810 (detail), Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon © RMN

1836 – TWO FAILED COUPS D’ÉTAT

1836 – TWO FAILED COUPS D’ÉTAT

Louis-Napoleon’s cousin became for a short moment “Napoleon II” when Napoleon I abdicated in his favoir in 1814. However, the Allies, who had conquered Napoleon at Waterloo, forcing his abdication, refused to place his son on the throne: Louis XVIII restored the Bourbon monarchy while the Emperor’s son remained at the court of Vienna, where he was known simply as the “Duke of Reichstadt”. When the frail young man, heir to the Imperial throne, died on 22 July 1832, his cousin Louis-Napoleon became the guardian of the Empire’s legacy.

From this moment, Louis-Napoleon, still in exile, tried to gather the Bonapartists around him. On 30 October 1836, he began to stir up opposition to the regime with a first march on Paris from the city of Strasbourg. This first “coup d’état” (an attempt to take power by force) was very quickly thwarted; King Louis-Philippe then sent Louis-Napoleon into exile in the United States. He returned to France the following year, however, in order to be with his mother, Hortense, shortly before her death on 5 October 1837.

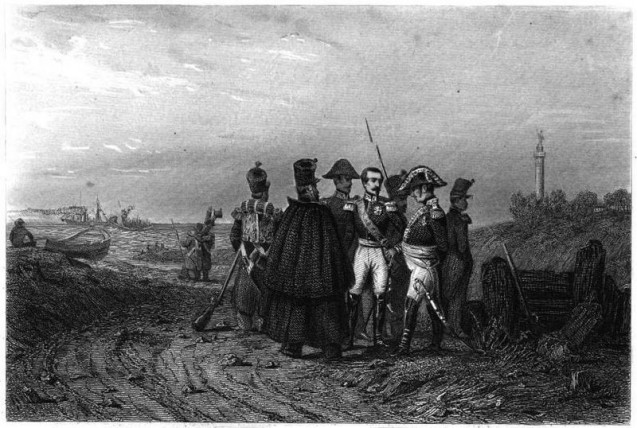

Louis-Napoleon continued his political activities from London where he prepared a new coup d’etat. From the 4th to the 5th of August, 1840, he disembarked at Boulogne-sur-Mer in the hope of rallying to his cause the 42nd regiment of the line stationed there. The attempt again ended in failure: Louis-Napoleon was wounded, taken prisoner and soon tried and sentenced to life imprisonment at Fort Ham in the north of France on 6 October 1840.

The conditions of his imprisonment were rather agreeable: Louis-Napoleon lived in an apartment within the fortress, isolated but comfortable. He took advantage of his six years of imprisonment to read and write, in particular his most famous political essay: “The Extinction of Pauperism” in 1844. On 25 May 1846, Napoleon’s nephew managed to escape from the fort and returned to Great Britain.

Illustration: Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in Boulogne (Landing in August 1840), anonymous

!["Apparition de la grande famille" [Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Président de la IIe République] © BnF](https://www.napoleon.org/wp-content/thumbnails/uploads/2016/12/1848-apparition_de_la_grande_famille_-_btv1b530188634-tt-width-637-height-484-crop-1-bgcolor-ffffff-lazyload-0.jpeg)

1848 – THE PRINCE-PRESIDENT

In 1848, there was revolution in France again. Following the abdication of the king, Louis-Philippe, a Republic (the Second French Republic) was proclaimed on 24 February 1848. In the elections for the “Assemblée” that followed, three factions emerged: moderate republicans, monarchists belonging to the “Parti de l’Ordre”, and socialists. Resolutely conservative, the new Assemblée offered support to the government of General Cavaignac and his authoritarian policies. It is in this context that Louis-Napoleon, supported by the Parti de l’Ordre, was elected president on 10 December, taking up residence in the Palais de l’Elysée, the new seat of Republican power. A conservative Assemblée and government now in place, the Second Republic became a battleground between the resurgent monarchists, looking to re-establish the monarchy, and the republicans, who sought more egalitarian and social policies.

When Louis-Napoleon became president, he made a point of his Imperial pedigree: already from this period, the shadow of the Empire hovered over his mandate.

Illustration: Appearance of the great family [Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, President of the Second Republic] © BnF

1851 – A SECOND NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE

Having become president of the Republic, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte allowed the conservatives in the Legislative Assemblée to conduct reactionary policies (suppression of universal suffrage, curtailment of press freedoms). Faced with these unpopular measures, the Prince-President gradually presented himself as the champion of universal suffrage and the protector of the common worker and of religion. Having failed to obtain a revision in the constitution that would allow him to be re-elected in 1852, Louis-Napoleon dissolved the Assemblée nationale on 2 December 1851, in direct violation of the constitution. On 21 December, the Corps électoral was asked to endorse the new governmental principles: executive power would be accorded to an elected president who would rule for ten years. He alone would be able to initiate legislation and would have the power to name his ministers who would be responsible only to him. The plebiscite was largely in favour: 7,481,231 voted for while 640,292 voted against. The legislative elections which were held in February 1852 were equally favourable to those who supported the new government. A new plebiscite on 21 November preceded the regime change: on 2 December 1852, the Second Empire was established. The Prince-President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte officially became Napoleon III, Emperor of the French.

Did you know? Louis-Napoleon called himself “Napoleon III” (rather than “II”) because Napoleon I’s son (who became Napoleon II) had reigned for a very short period of time following his father’s abdication in 1814.

F.X. Winterhalter, “Napoleon III, Emperor of the French (1808-1873)” (detail) Versailles, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon © RMN

1853 – UN MARIAGE ET LES GRANDS TRAVAUX D’HAUSSMANN

1851 MARRIAGE AND THE BUILDING PROJECTS OF BARON HAUSSMANN

In 1853 the newly-crowned sovereign sought to ally himself with a ruling family in Europe, but such a union could not be negotiated. Napoleon III married Eugenie de Palafox-Portocarrero de Guzmán, known as Eugénie de Montijo, a young Spanish woman with whom he had fallen in love.

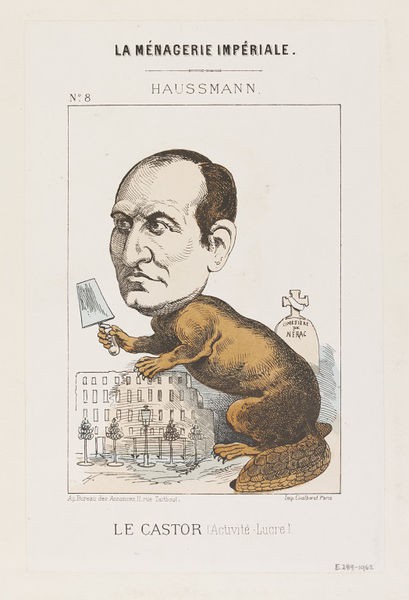

The same year, Napoleon III charged Baron Haussmann with the transformation and modernization of Paris. Paris was turned into a building site as new roads and open spaces were built to improve the traffic in the city. Opinion remained divided however: for some, Paris lost a lot of its charm as many old areas were cleared out and destroyed. For others, the huge buildings that rose out of the rubble, with their near-identical facades, brought an ordered elegance to the city.

Find out more about the life of Empress Eugenie.

Illustration: During the Second Empire, opposition to Napoleon III and Haussmann’s building projects was very vocal. A collection of satirical sketches called ‘La menagerie impériale’, published after the fall of the Empire, caricatured Haussmann as a beaver, an animal well-known for its building abilities but which often produced constructions which were considered invasive by man. © Fondation Napoléon

1854 – THE CRIMEAN WAR

War broke out between France, protector of eastern Christians since the time of Charlemagne, and Russia, the seat of the Orthodox Church since the fall of Constantinople to the Turks. Both countries sought to maintain their influence in the east. Discussions over the restitution of a silver cross stolen from a Christian church in Bethlehem by members of the Orthodox Church mask the real issues behind the war. France, England and the Ottoman Empire allied against Russia; the battleground was Crimea, near to the Black Sea. On 20 September 1854, the French secured an important victory at Alma. Then on 8 September 1855, a year-long siege led to the capture of the port of Sebastopol. Peace was concluded with the Treaty of Paris on 30 March 1856. Emerging victorious from this test, Napoleon III consolidated his regime and its place in Europe.

Did you know? This was the first war of the industrial era. Armies employed steam engines, battleships and explosive shells and communicated using the telegraph.

I.A. Pils, “Landing of allied troops in Crimea in 1854” (detail), Musée Fesch, Ajaccio © RMN

1855 – PARIS HOLDS ITS FIRST “EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE”

In 1855, four years after the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London, Paris organized its own exhibition. Visitors came from France and all over Europe to discover the new inventions, works of art and the exotic animals and plants on display. A huge building, the Palais de l’Industrie et des Beaux-Arts was specially built to house the exhibits, from France and other countries. The building was destroyed in 1896. Between 15 May and 15 November 1855, the exhibition received more than five million visitors.

Did you know? Visitors to the exhibition could find out more about wondrous new inventions such as the saxophone and black and white photography (colour photography was invented later on, in 1870). New industrial machinery was also on display, destined to mechanise agriculture and improve productivity.

Illustration: M. Berthelin, “Palais de l’Industrie, a perspective view” (detail), Musée d’Orsay, Paris © RMN

1856 – THE CONGRESS OF PARIS

Defeated in the Crimean War (1854-1856), Russia was forced to discuss peace. The Congress of Paris began on 26 February 1856 and brought together the countries of France, Austria, Piedmont, Turkey, Prussia, Russia and England. The Ottoman Empire received a guarantee of its independence and of the entirety of its Empire. Austria, through skilful diplomacy, secured the important benefit of access to the Danube Estuary. Russia was forced to abandon its protectorate of the Greek Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. For France, the Congress of Paris was a revenge for the Congress of Vienna in 1815: as well as having the congress held in Paris, the French were also able to direct proceedings and secure concessions for their allies. France once again became an important diplomatic power. Much to the dismay of the Austrians, the question of Italian unity was also raised, by Count Walewski, the French minister for foreign affairs, who was presiding over the congress. On 30 March 1856, the treaty was signed, an event which coincided with the birth of the Prince Impérial.

Did you know? During the Crimean War, a photographer was employed for the first time by a government to produce a photographical report. Roger Fenton, a British photographer, took about 360 photos between March and June 1855.

Illustration: E.L. Dubufe, “The Congress of Paris, 25 February to 30 March 1856” (detail), Musée national du château de Versailles © RMN In the foreground, Count Orloff, the Russian representative, turns away from Walewski and Lord Clarendon who seem to be inviting their Ottoman ally to the negotiations table. Cavour, the architect behind Italian unity is standing next to Lord Cowley. Austria is represented by Boul.

More about this painting.

1858 – THE MEETING IN PLOMBIÈRES

During the 19th century, the question of Italian unity preoccupied the rulers of Europe. Since the Congress of Vienna, Italy was divided into numerous states which came under Austrian authority. Seeking to secure independence and unification, Italian revolutionaries lead a number of uprisings on the peninsula. One of these lead to the creation of the Roman Republic. This was quickly quashed following French intervention and the Pope was re-established in 1849. Holding the Emperor personally responsible, the Italian republican Felice Orsini (1819-1858) meticulously plotted the assassination of Napoleon III in order to create confusion in France and thus, as a result, in Italy. On 14 January 1858, a number of bombs exploded on the Rue Le Peletier as an Imperial cortege made its way to the opera. More than one hundred people were injured but the Imperial couple was unhurt. Quickly arrested along with his accomplices, Orsini was executed on 13 March. Napoleon III decided to meet with Cavour, the President of the Piedmontese Consilio, at Plombières on 21 July 1858. The Emperor promised to support Cavour in the event of Austrian aggression as well as assist in the reorganization of Italy, provided that the Pope remain leader in Rome. In exchange for this assistance, it was expected that France receive the dukedoms of Nice and Savoy. On 23 January 1859, a treaty of defensive alliance was agreed with France based on what was discussed at Plombières.

A diplomatic marriage was also concluded between France and the house of Savoy. On 30 January 1859 the Prince Napoleon, the Emperor’s cousin, married Princess Clotilde of Savoy, the oldest daughter of Victor-Emmanuel II of Savoy, Duke of Savoy, Prince of Piedmont and King of Sardinia. Victor-Emmanuel later went on to become King of Italy in 1861.

Did you know? The Emperor and his wife owed their lives to the ingenuity of the imperial carriage’s designer: the latter had in fact incorporated steel plates into the walls of the car.

Illustration: Michele Gordigiani portrait of Camillo Benson, Count of Cavour © Wikipedia

1859 – SOLFERINO AND THE TREATY OF ZURICH

As agreed at Plombières in 1858, Napoleon III supported a number of the Italian states that declared war on Austria. The French army won victories at Magenta (4 June 1859) and at Solferino (24 June). This last battle was particularly bloody and shocking. Even though victorious, Napoleon III was quick to sign the armistice with Austria at Villafranca on 8 July 1859. The Treaty of Zurich was signed on 10 November between Austria and Sardinia. Austria ceded a large part of Lombardy to France, who in turn retroceded it to the Piedmontese Kingdom. This region would become the driving force behind Italian unification. On 24 March 1860, the Treaty of Turin confirmed the reattachment of Savoy and the dukedom of Nice to France.

Illustration: Anonymous, Napoleon III giving orders at the battle of Solférino, 24 June 1859, 1861 © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Franck Raux

1861 – THE FAILED MEXICAN EXPEDITION

During the 19th century, Mexico was embroiled in a series of never-ending civil wars and had, since independence, experienced a number of short-lived regimes. In 1858 the arrival in power of Juarez, a liberal politician, was a turning point for the country. Faced with Mexico’s deplorable economic situation, he declared a moratorium (delay) on foreign debt repayments on 17 July 1861. The three countries most affected by this decision, Great Britain, Spain and France, signed an alliance agreement on 31 October 1861 in London with the intention of intervening in Mexico. France’s position in this, however, is ambiguous: the loan that they had given to Mexico was modest and served more as a pretext in Napoleon III’s designs to create a buffer region in South America. The Emperor wanted to create a French colony in Mexico which would allow further expansion in the southern regions. The ultimate aim was to create a Catholic Empire to act as a counterweight against the growing influence of the United States, which was Protestant. The first expedition (end of 1861 to beginning of 1862) was hardly convincing and England and Spain signed the Treaty of Soledad with Mexico in February 1862. The European powers agreed to withdraw their troops in exchange for compensation. France eventually signed the agreement but Napoleon III rejected it and sent another expeditionary force. After the long siege of Puebla (March – June 1863) followed by the battle at Camerone (30 April 1863), Mexico fell to French forces on 5 June 1863. Napoleon installed Maximilian, the brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, on the Mexican throne. However, Maximilian’s carefree temperament and lack of political nous made consolidating his throne very difficult and while Juarez received the support of the United States, Maximilian’s military errors began to build up. Refusing to abdicate, he was taken prisoner and executed in Queretaro on 19 June 1867.

Illustration: Manet, “The execution of the Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico”, Kunsthalle (Mannheim, Germany) © RMN

1862 – THE TREATY OF HUẾ AND THE FRENCH IN COCHINCHINA

The French Revolution dissolved or cleared out many of the French Catholic evangelical missions at the end of the 18th century. During the 19th century, these missions began to return and multiply, particularly during the Second Empire, and the French Catholic Church organised a number of missions in the Far East. Cochinchina (today South Vietnam) was, however, hostile to the French religious message and in 1832 passed a law authorising the persecution of priests. In 1857, the Jesuit R. P. Diaz mobilised the Catholic press to inform the French population of what was happening to the missionaries in Cochinchina. The French government sent a naval force commanded by Admiral Rigault de Genouilly, who was given the job of negotiating the question of religious freedom in Cochinchina with Tu Duc, the Emperor of Vietnam since 1847. Tu Duc refused point-blank and Rugault took Saigon, in 1859. The Vietnamese Emperor was forced to submit and signed the Treaty of Saigon on 5 June 1862. France secured the Catholic Church’s religious freedom, commercial and navigational rights in the area, three provinces that previously belonged to Cochinchina and a war indemnity. It was not until 14 April 1863, however, that the treaty was confirmed by the Treaty of Huế.

Did you know? Cochinchina was a very fertile colony, with corn fields, and coconut, fruit and rubber trees. These raw materials led to commercial growth and a huge increase in exported goods.

Illustration: Morel-Fatio, An episode from the expedition to Cochinchina in 1859: the capture of the citadel and upper-town of Saigon by Vice-Admiral Rigault de Genouilly commanding a Franco-Spanish expeditionary force, 17 February 1859, (detail) Musée National du Château de Versailles © RMN

1864 – THE WORKERS’ RIGHT TO STRIKE

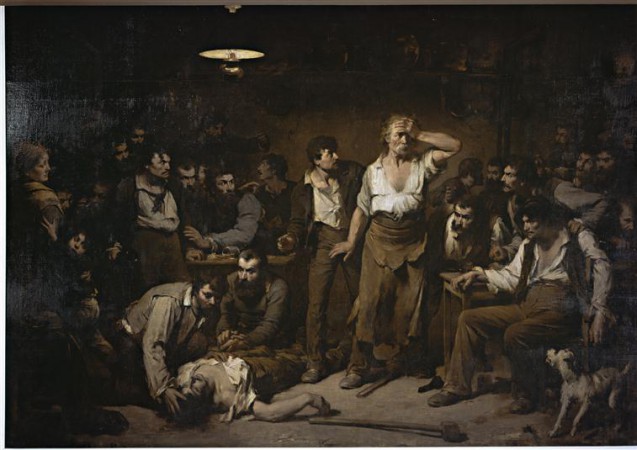

In the 19th century, working conditions were very harsh. Adults would generally work between ten and fifteen hours a day, for very little pay. Their children would often be sent out to work from the age of seven. Breaks were almost nonexistent, there were no holidays and the workers only got one day off a week. If they were ill, they were not paid. They could not even demand any changes to working conditions as the Chapelier law in 1791 had outlawed strike action. On top of this, in employment disputes, the advantage lay with the employer and not with the employee. Under the Second Empire, Napoleon III pursued social policies aimed at softening the negative effects that rapid industrial development in France had had on the workers. In 1864, a law according the right to strike was passed, with the condition that workers were free to decide themselves whether they participated or not. However, the beneficiaries of this law were restricted by the fact that there was no freedom of association. In 1868, another law was passed which authorised non-political gatherings provided notice of at least three days was given.

Did you know? The number of strikers grew each year, from 20,000 in 1864, to 28,000 in 1865, and 32,000 in 1867.

Illustration: Paul-Constant Soyer, Blacksmiths’ strike (c.1870) © RMN-Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz

1865 – INAUGURATION OF THE “GARE DU NORD”

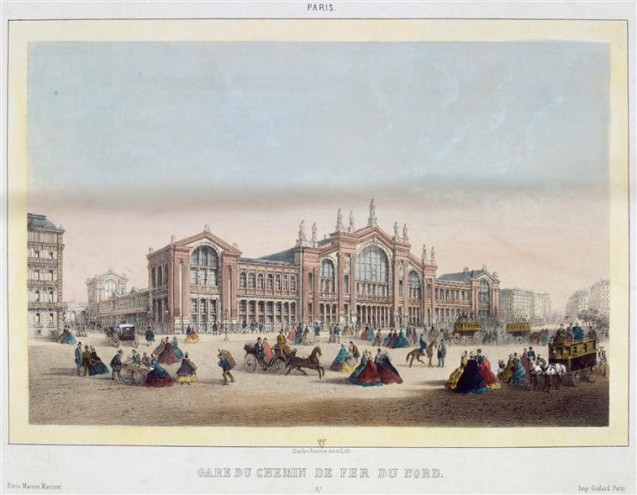

In 1865, the Gare du Nord station was completed. It was seen as a symbol of the development of the railway in France. Travel between the provinces and Paris was made easier and goods could be transported more quickly and in greater quantities. More and more of the richer families in France could also now take holidays by the sea or in the mountains. Each year about 700km of railways were installed and by 1870, France had a rail-network of almost 18,000km.

Illustration : Charles Rivière, The station of the Northern railway line, c.1870-1880 © Fondation Napoléon

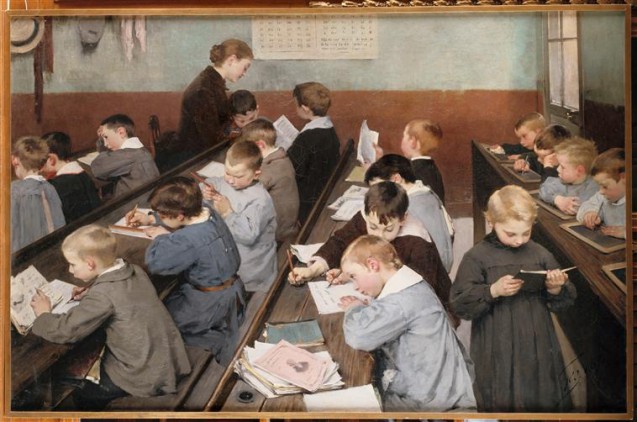

1867 – BOYS AND GIRLS AT SCHOOL!

Charlemagne was the first to create a school in France, when in the year 781 he started the École du Palais with the aim of instructing the men of his inner circle. The first real school reforms were in 1833 with the Guizot law which made primary education free to the poorest families, but was still reserved only for boys. It was under the Second Empire that real improvements began to appear: each school had to have an educational library, the number of teachers was increased, and night school classes were introduced. An 1867 circular was a turning point: the education minister Victor Duruy made primary education free to everyone and open to girls! However, only towns of more than 500 inhabitants were required to open a school for girls and it was not until 1882 that primary education became obligatory and secular.

Did you know? The number of children in school rose from 2 million in 1830 to 5.6 million in 1880.

Illustration : Henri Jules Jean Geoffroy, En classe, le travail des petits © RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

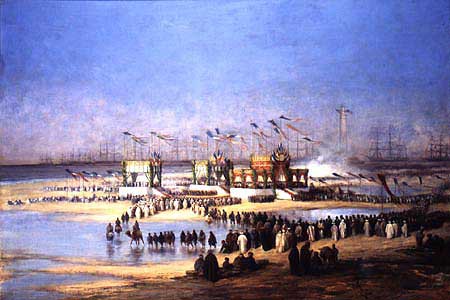

1869 – THE INAUGURATION OF THE SUEZ CANAL

In 1497, Vasco de Gama (1469-1524), a Portuguese sailor, discovered the route to the Indies via the Cape of Good Hope. Even though this route offered distinct advantages to sea-based commerce, the journey was long for ships coming from Europe. During his Egyptian campaign (1798-1801), Napoleon I had become interested in the possibility of a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Ferdinand de Lesseps (1805-1894), a French diplomat and entrepreneur, took up this project a few decades later. The work began in April 1859 thanks to the generous aid given by the Egyptian Viceroy, Mohammed Saïd (1822-1863). De Lesseps obtained from the viceroy permission to create the Suez Canal Company which would undertake to drill through the isthmus, as well as 20,000 fellahs (workers) and 60,000 hectares of land. The Viceroy’s decisions were however monitored by the Sultan who was reluctant to sign the firman (Islamic edict). He was also influenced by England whose politicians were against the Suez project. The death of Saïd strengthened the English position as the Viceroy’s successor, Ismaïl, went back on the agreements made with de Lesseps. Napoleon III was asked to step in and arbitrate. The Egyptian government reclaimed the 60,000 hectares and the fellah workforce but the company was compensated to the tune of 84 million Francs. Work restarted at the end of 1864 despite financial difficulties caused by the period of inactivity and the costs already incurred. In August 1869, the canal was completed. It measured 162km in length, 54m in width and 8m in depth. On 17 November 1869, the Empress Eugenie was present at the canal’s inauguration as the French Emperor’s representative.

Illustration : E. Riou, Inaugural ceremony of the Suez canal at Port-Saïd, 17 November 1869 © RMN

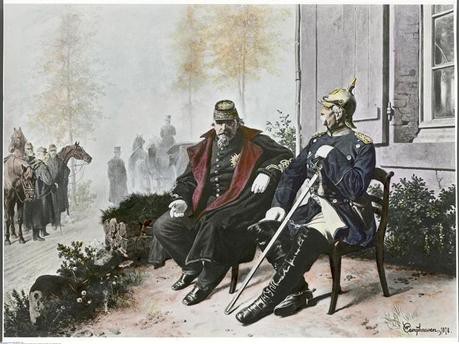

1870 – SEDAN AND THE FALL OF THE EMPIRE

Since the 1860s, under the instigation of the chancellor (prime minister) Bismarck, Prussia has a policy of aggressive expansion with the secret goal of consolidating the independent German regions and making them into a single unified empire. The kingdom of William I attacked Denmark in 1864 and then in Austria in 1866.

In 1870, the tensions between France and Prussia intensified around the attribution of the Spanish throne. One of the candidates for the resumption of this throne was none other than a cousin of William I, an option which Napoleon III wanted to avoid at all costs. The cousin of the King of Prussia was finally dismissed but Bismarck took advantage of this tense context to provoke Napoleon III by making the rumour that the French ambassador was humiliated by the King of Prussia. The Emperor of the French, who had already begun to mobilize his troops, decided to declare war on Prussia on 19 July 1870. But the difficult expedition to Mexico, which had been completed almost three years earlier, had weakened the French troops who were not ready for such a conflict. Moreover, Napoleon III received no support from other European monarchs in this declaration of war in which he was considered the aggressor. William I, on the other hand, received the support of several German states, including from the South, despite the fact that they were independent of Prussia.

The French were crushed by the German army. On 1 September, Napoleon III and his troops fell back to the fort in the town of Sedan. The next morning, Napoleon III capitulated and was taken prisoner. He was sent to Germany (the castle of Wilhemhöhe in Kassel, in Westphalia) where he remained in captivity for several months. The fall of the Second Empire was officially declared on 4 September 1870, a Republic was proclaimed and a provisional government put in place while France was still at war with Germany. The siege of Paris began on 19 September and the capital finally fell a hundred days later on 28 January 1871.

Illustration : Wilhelm Camphausen (after), Napoleon III and Bismarck on the morning after the battle of Sedan 2 September 1870 © BPK, Berlin, Germany

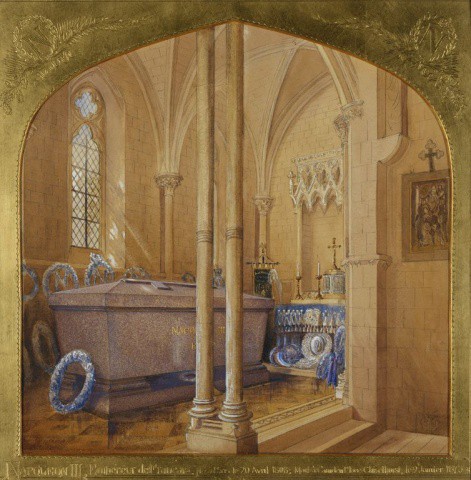

1873 – THE DEATH OF NAPOLEON III

In March 1871, Napoleon III joined his family in exile in England, welcomed by Queen Victoria who had much respect for the Imperial family. There they took up residence at Chislehurst in Kent. Whilst the Prince Imperial took up studies in a military school, Napoleon III thought of publishing works and was following closely what was happening in troubled France. The ravages of the war with Prussia, the revolt of the Parisians during the Commune of 1871, and the difficulties which befell the new Republic, gave hope to the exiled Emperor that a return was possible. But he has been subject to kidney stones for years and his health is weakening. After two operations, the defeated Emperor died on 8 January 1873.

On 1 June 1879, the Prince Impérial, who was enrolled in the British army, was killed on Mount Itelezi in Zululand. The area in southern Africa had revolted against England who sought to colonise the area. His body was returned to England to be buried next to his father’s. The death of the Prince Impérial marked the end of the Bonaparte dynasty. After 1879, Eugenie moved to Farnborough where she had an abbey built to house the mortal remains of her husband and son. She was buried there herself in 1920.

More about the Prince Impérial

Photography developed significantly in the years after 1860, and the Imperial couple posed frequently in front of the camera – thus creating portraits which are very well known today. The Imperial family is shown here in exile in their residence in Chislehurst, England, after the fall of the Empire. The photograph is in fact a photomontage composed of separate images of Napoleon III, the Empress Eugenie and the Prince Impérial. (© Fondation Napoléon)

To learn more about the reign of Napoleon III have a look at this Napo Factfile.