The Consulate and the Empire are two key periods in the history of France and of Europe. Here you can read about Napoleon’s early years, his coming to power, and other events during his reign. Some of these dates are expressed using the system of the Republican calendar. Click here to find out more about the Republican calendar.

1769 – THE BIRTH OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

On 15 August 1769, Napoleon Bonaparte was born in Ajaccio, in Corsica. The Bonapartes were a noble family who owned land, vineyards, and a comfortable house, but they were not always well-off. Bonaparte’s father never stopped trying to consolidate his family’s wealth and social standing. In 1771, he succeeded in having his family’s noble Tuscan origins recognised by France, which meant that not only could his sons benefit from study grants handed out by the king, but they could also attend schools reserved for the nobility. Napoleon’s first few years at school in Autun and then at military school in Brienne were difficult: his Corsican accent and his solitary nature frequently singled him out for teasing and jokes. He then moved onto military school at Paris where he received his officer’s diploma on 28 October 1785. His first regiment was stationed in Valence, in the south of France.

Did you know? Corsica was a dependent of the Genoan Republic until 1768, when it came under French control.

Illustration: Léonard-Alexis Daligé de Fontenay, The birthplace of Napoleon I in Ajaccio © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) / Jean Schormans

1789 – NAPOLEON AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

From 1787, Bonaparte alternated between Paris and Corsica. In Ajaccio, he participated in politics, supporting the unification of Corsica with France. This brought him into conflict with Pascal Paoli, who advocated Corsican independence and who was supported by the English.

The French Revolution in 1789 pitched the defenders of the monarchy, the privileged aristocracy and the high-ranking clergymen against the partisans for a more egalitarian society, known as republicans. The insurrection crystallized with the abolition of privileges on August 4, 1789. Bonaparte was only 19 years old. The revolutionary legislative assembly, which was to transform the absolute monarchy into a constitutional monarchy, gave way to the Convention in 1792, which set up the First French Republic. The new regime tried to find a balance between the moderates (Girondins) and the more radical faction (Montagnards).

After the king was executed in 1793, political life was irredeemably and dramatically changed. The Regime known as the “Terror” was imposed by the Montagnards. The same year, 1793, because of their allegiance to the Convention, and opposition to Corsican Independence, the Bonapartes were forced to leave the island and seek refuge in Toulon, on the south coast of France. Whilst the Terror ended on the 9 Thermidor Year II (July 27, 1794), a new constitution was drawn up for a year, culminating in the Convention of 5 Fructidor Year III (22 August 1795). In Paris, Napoleon took part in crushing the royalist insurrection against the Convention (13 Vendémiaire Year IV (5 October 1795), which resulted in his being named Division General on 16 October 1795.

Did you know? On 10 August 1792, Napoleon was present at the storming of the Palais des Tuileries, during which the palace was sacked and pillaged, the Royal Guard massacred and the Royal family forced to seek refuge at the Assembly. Profoundly influenced by this dramatic experience, Napoleon would later focus all his attention on avoiding popular uprising in Paris during his reign.

Illustration: Raffet, “13 vendémiaire, Saint Roch 1795” (detail), Musée National du Château de Malmaison © RMN

1796 – THE FIRST ITALIAN CAMPAIGN

On 2 March 1796, the Directory named Napoleon Commander-in-chief of the Armée d’Italie and dispatched him with orders to counter Austrian influence in Italian territory. The Convention thus wanted to help young republics known as “sisters” of the Revolution to free themselves from the monarchies of the Ancien Regime and spread revolutionary ideals. This plan also aimed to oblige the enemy European powers of the Republic, united in coalition, to let go of the front that they had opened in France in 1792.

The young general was able to put into practice the military strategy that he had been developing in the course of his reading: target the enemy’s weak point, move quickly, and attack with surprise to gain a psychological advantage. April and May 1796 were marked by a series of victories, but in the summer, the Austrians took the advantage. On 15 November, Napoleon launched an attack near Rivoli, and after three days of fighting, achieved victory. The Austrians signed the treaty of Campoformio on 17 October 1797. Seven victories in seven months against a much larger army demonstrated that General Bonaparte was a great strategist. He also turned his hand to installing new ‘sister’ republics in Italy (the Cisalpine Republic and the Ligurian Republic).

Did you know? It was during this first campaign that Napoleon began to create the image of his invincibility and divine providence. He founded two newspapers, Le Courrier de l’armée d’Italie and La France vue de l’armée d’Italie, intended to maintain army morale and to inform the French public of their General-in-chief’s victories. “Bonaparte flies like lightning and strikes like thunder. He is everywhere and sees everything. He is sent by the Great Nation.” It was a publicity campaign before its time!

Portrait: Gros, “General Bonaparte on the bridge of Arcola, 17 November 1796”, © Château de Versailles Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin

1798 THE EGYPTIAN EXPEDITION

In 1798, the Directory sent Napoleon to Egypt to combat England’s growing commercial influence in the area. Keeping the expedition secret for as long as possible was crucial; to slow any possible counter-attack by the English Navy, commanded by Admiral Nelson, Napoleon had his ships leave from different ports. Landing in Alexandria on 1 July, Napoleon and his troops were faced with a very hot climate and an uninhabitable terrain, blessed with very few resources. Nevertheless, the French army challenged and overturned the army of Mamluks, (reputed warriors, kidnapped in their youth in Muslim countries and attached to a sultan or caliph, whose leader, on the orders of Mourad Bey, had taken power with Ibrahim Bey in Egypt), at the Battle of the Pyramids near Cairo on 21 July. The French settlement in Cairo provoked an uprising of the native inhabitants which was harshly suppressed. At the same time, the French fleet lay in Abukir Bay, believing itself to be safe and protected. But on 1 August, Admiral Nelson blocked the French fleet from escaping and bombarded the ships. It was a disaster for the French fleet: 1,700 sailors were killed and almost all the ships were sunk. On top of this, the Syrian conquest, launched in January 1799, finished in defeat. Despite the land-based victory at Abukir on 25 July 1799, Napoleon decided to return to France, arriving back in Paris on 16 October. The departure of the French on 30 August 1801 confirmed English dominance in the region.

Did you know? The military campaign also provided the opportunity for a scientific expedition. Napoleon was accompanied by 160 scholars, geologists, botanists, chemists, and doctors. Besides offering logistical support and treatment for the soldiers, the scientists also made detailed drawings of the temples, pyramids and present-day towns, studied the arabo-islamic social customs and discovered the flora and fauna of Egypt. All these discoveries are described in detail in a magnificent ten-volume publication called La Description de l’Egypte (“Description of Egypt”).

Find out more about the Egyptian Campaign.

Illustration: Gros, “Napoleon Bonaparte haranguing the army before the Battle of the Pyramids 21 July 1798”. Musée du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Daniel Arnaudet / Jean Schormans

THE COUP D’ETAT OF 18 BRUMAIRE YEAR VIII

In 1799 the Directory was a government in decline, corrupt and hated by the French. Some of the Directors solicited Bonaparte’s return from Egypt, who agreed to help them overthrow the government. On 18 Brumaire (9 November), the two legislative assemblies were moved to the Château de Saint Cloud under the pretext that they needed protection from a potential plot. Bonaparte was charged with the protection of the “deputes”. He gave a confused speech in front of the assemblies; this caused trouble in the ranks, and Bonaparte was heckled by the men present. Order was restored thanks to the intervention of General Murat and his troops. The next morning, the constitution for a new, provisional government was passed. Revealing his political ambitions, Bonaparte imposed himself as candidate for First Consul. Under the new constitution of Year VIII signed on 22 Frimaire Year VIII (13 December 1799), he could name not only the members of the “Conseil d’État” who drafted the laws, but also ministers, ambassadors, army officers and judges. The “Tribunat” and the “Corps législatif” were charged with the voting of the laws and the “Sénat” was the ‘guardian’ of the constitution.

The Consulate (1799-1804) oversaw the modernisation of France: the Banque de France was created and the currency stabilised, France underwent an administrative organisation (the creation of “départments” and “préfets”), the “Code Civil” was written, the “Légion d’honneur” was instituted, and canals, roads and tunnels were built throughout French territory. These new institutions created during the Consulate that survive to this day were known as the “Masses de granite”. Find out more.

Did you know? Bonaparte’s installation as First Consul gave rise to both Republican and monarchist opposition and that a number of plots would threaten the stability of the regime. On 24 December 1800, while on his way to the Paris Opera, Napoleon survived a bomb attack on rue Saint-Nicaise. Illustration: Bouchot, “Le Dix Huit Brumaire, 10 November 1799. Bonaparte in the conseil des Cinq-Cents at Saint-Cloud”, Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)

1800 – ITALY PART TWO: PEACE IN EUROPE

Austria and England were not prepared to accept the emergence in European politics of a Republican France under an ambitious First Consul Bonaparte. General Moreau was sent to fight Austrian presence in Germany, while Bonaparte looked to repeat his previous exploits of the first Italian campaign. On 14 June 1800, he narrowly defeated the Austrians at Marengo, a victory that led to the signature of the Peace of Lunéville in February 1801. After numerous diplomatic exchanges, England signed the peace treaty of Amiens in 1802. Europe entered a period of relative peace…

Did you know? In order to catch the enemy unawares, Napoleon and his entire army, including canons, munitions and horses, crossed the Alps. During May there was heavy snow and the Austrians, who could not believe it, were taken completely by surprise.

Illustration: Thévenin, “The crossing of the Great St Bernard Pass, 20 May 1800. Château du Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

1801 – THE CONCORDAT, THE RELIGIOUS PEACE

Looking to wipe the slate clean on an unequal, monarchist and catholic society, the French Revolution had suppressed Catholicism and abolished the clergy. The creation of a secular cult, unpopular and poorly supported by the population, had severely disrupted French society and succeeded only in setting French citizens against each other. Concerned for civic peace, Bonaparte entered into discussion with the Holy See (the central government of the Catholic Church), resulting in the signature of the Concordat on 15 July 1801. Catholicism was recognised as the “religion of the French majority” and places of worship were reopened. Nevertheless, Bonaparte reinforced his control over the church by obtaining the power to name bishops, and the introduction of an oath of loyalty to the government that the clergy had to take.

Did you know? “Les Articles organiques” were appended to the Concordat after ratification by the Catholic Church. These “Articles”, which were never approved by the Pope, allowed Bonaparte to reinforce his political dominance over the spiritual authority held by the church since the Middle Ages.

Illustration: Baron Gérard, “The signing of the Concordat between France and the Holy See, 15 July 1801”, Musée National du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

1802 – THE ORDER OF THE LÉGION D’HONNEUR

A few days after having been voted “Consul for life” by the Sénat on 12 May 1802, Napoleon founded the order of the “Légion d’honneur” (“Legion of honour”) on 19 May 1802. After the disruption of the Revolution, this decoration intended to bring together French citizens based on values and talents such as courage, civic ingenuity, and art. It was not a military award; civilians, industrialists, scientists and artists, and men and women alike, could all receive the honour. Besides the medal and a title (“Grand Officier”, “Commandants”, “Officier”, “Légionnaire”), the recipient also received a regular allowance for life. The legionary had to pledge loyalty to the Republic and its government (and later on to the Empire and the Emperor).

Assistance could also be accorded to needy members and, concerned about the education of young girls, Bonaparte introduced educational centres for the daughters and granddaughters of titulars. The Légion d’honneur was accorded for the first time on 15 July 1802 at a grand and impressive ceremony held in the church of Saint-Louis des Invalides.

Did you know? The Légion d’honneur is part of the ‘masses de granit’, the name given by Napoleon to what he considered to be his most important laws that reorganised France during the Consulat.

Illustration: Debret, “First distribution of the Croix de la Légion d’Honneur in the Church of Les Invalides”, Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)

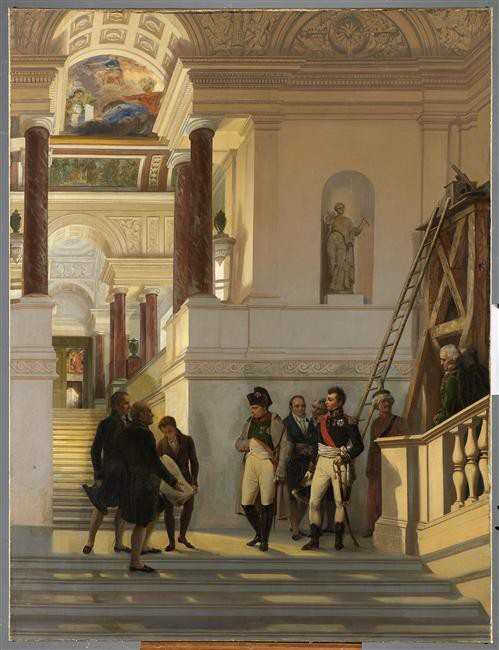

1803 –THE MUSÉE NAPOLÉON

In 1792, the Muséum Central des Arts was created, situated in the Palais du Louvre. The aim was to bring together the works of the greatest painters and sculptors, allowing the general public to admire them and artists to be inspired by them. In 1802, Napoleon named as head of the museum Vivant Denon, a man of prodigious artistic talents who had also accompanied Napoleon on his Egyptian expedition. Denon was in charge of acquisitions and official commissions for not only for the Musée Napoléon (as it was renamed in 1803) but also for the fifteen new provincial museums, created in Lyons, Bordeaux and Marseilles and other towns. Through the wealth of its collections, the museum was to reflect the power of the French state. Throughout his reign, Napoleon continued to re-organise the Palais du Louvre; he also commissioned contemporary artists to paint his portrait celebrating his political power, as well as works depicting (in the best light, of course) the events and the great successes of his reign, including coronations, Imperial marriages, treaty signatures and military victories. Every two years, the “Salon” for living artists would put on a public display of its works; some of these would end up hanging in imperial palaces or becoming diplomatic gifts.

Did you know? During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the French government enriched its collections by taking many works of arts from the museums of its defeated enemies? After the fall of the Empire, a large number of these works were returned to their original homes.

Illustration: Couder, “Napoleon I visiting the staircase of the Louvre guided by the architects Percier and Fontaine”, Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Thierry Ollivier

1804 – A YEAR OF CONTRASTS

After the foiling of a royalist plot in March 1804, Napoleon suspected that the duke was the instigator. After multiple attempts on his life, Napoleon wanted to put an end to these assassination plots as well as protect himself against any possible return of the Bourbon monarchy. The duke was arrested and, after a quick trial, executed on 21 March. His death gave rise to cries of protest in every royal court in Europe.

Almost a month later, a new constitution was created: the First Empire was proclaimed by the senatus-consulte (vote of the Senate by law) of 28 Floreal, Year XII (18 May 1804). This senatus-consulte was approved on 6 November later the same year.

On 2 December 1804, Napoleon was crowned Emperor of the French. Over 12,000 people were present at the ceremony which lasted for more than four hours in the freezing Cathedral of Notre-Dame. The Pope also made a special trip from Rome for the ceremony. However, in placing the crown upon his head himself and crowning his own wife Josephine, Napoleon succeeded in reducing the Pope to a simple blessing of the ceremony, thus reaffirming his power in face of the Catholic Church. Napoleon planned every detail of the ceremony which was intended to put him on an equal footing with other European monarchs. However, only a few months earlier, the godson of Louis XVI, the Duc d’Enghien, had been executed on Napoleon’s orders.

Illustration: David, “The coronation of Emperor Napoleon I and the Empress Josephine at Notre Dame de Paris, 2 December 1804”, Musée National du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski

1805 – VICTORY AT AUSTERLITZ

In 1805, England organised a new coalition against France, which included Austria, Prussia and Russia. The Grande Armée (the French Imperial army) won a series of victories, including Ney’s victory at Elchingen on 14 October and Napoleon’s victory at Ulm on 20 October. French troops entered Vienna on 14 November, and on 2 December, a year after his coronation in Paris, Napoleon crushed the Russian and Austrian troops at the Battle of Austerlitz. The Austrians signed the peace treaty at Presbourg on 26 December. The war lasted for two years: the French double-victory at Jena and Auerstadt on 14 October 1806 against the Prussians followed by victory over Russia at Friedland on 14 June 1807 confirmed Napoleon’s dominance in Europe. On 8 July 1807, Russia and Prussia were forced to sign the peace treaty at Tilsit, and Napoleon created the Duchy of Warsaw from Polish territory taken from Prussia.

Illustration: Gérard, “Battle of Austerlitz, 2 December 1805”, Musée National du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)

1806 – TOWARDS THE GRAND EMPIRE

In 1806, Napoleon appeared invincible. Emperor of the French since 1804, he also became King of Italy in 1805, Protector of the German Confederation in 1806 and had been Mediator of the Helvetian Confederation since 1803. Little by little he installed family members on the European thrones: his stepson Eugene de Beauharnais was made Viceroy of Italy in 1805, his brothers Louis and Joseph became Kings in Holland and Naples respectively in 1806, and later on, in 1807, Jerome was named to Westphalia. In 1808, his brother-in-law Murat was also installed as King of Naples.

However, the main enemy was still England, who controlled the seas and world trade. The development of English industries, notably textiles, rested on the exportation of the raw materials from the colonies in India and the Caribbean. Realising that he could not launch a direct attack on the English navy (the French suffered a bitter defeat at Trafalgar in 1805), Napoleon decided to weaken England’s economy by imposing a continental blockade in 1806. A decree obliged all French and allied ports (including Holland and Spain) to refuse entry to British ships. However, some of the allies were reluctant to apply the blockade with any real conviction for fear that their own trade would suffer, and smuggling increased. On top of this, Napoleon was forced to mobilise a lot of men to oversee the blockade, many of whom were taken from army contingents.

Illustration: James Gillray, Dividing up the world © RMN. Caricature showing Napoleon (right) and the British Prime-minister William Pitt (left) in 1805 greedily serving themselves large portions of the world.

1808 – THE SPANISH CAMPAIGN

Traditionally, Spain had been an ally of France, playing an important role in the continental blockade of England trade. However, in April 1808, Napoleon’s concern over dynastic conflicts between the king of Spain Charles IV and his son Ferdinand led him to install his own brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. The new king was poorly received by the people in Madrid and there was an uprising on 2 May. France’s repressive response on 3 May fuelled opposition in the country, which was supported by a heavyweight ally, England. Napoleon was victorious at Somosierra on 30 November and Madrid capitulated on 4 December, but he was soon obliged to return to Paris due to the Austrian threat. The conflict, a real war of independence for the Spanish, also contributed to the weakening of the Napoleonic army and served to demonstrate to the whole of Europe that it was no longer invincible. Despite several victories, the French troops, exhausted by obstinate guerrilla fighting, were defeated at Vitoria on 21 June 1813 and shortly after Joseph was forced to yield the throne to King Ferdinand VII.

Illustration: Goya, Dos de Mayo 1808, Madrid (the 2nd May) © Museo Nacional del Prado, Dist. RMN-GP

1809 – A DIFFICULT AUSTRIAN CAMPAIGN

In April 1809, Austria was looking for revenge. Thus began the hardest-won campaign of Napoleon’s career, a campaign notable for its victories (Eckmühl on 22 April, Ratisbonne on 23 April and Wagram on 6 July) but also for its defeats (the battle of Essling on 20-21 May for example). The victory at Wagram on 6 July imposed peace on the Austrians, which was signed in Vienna on 14 October. As well as losing Galicia to the Duchy of Warsaw, Austria was forced to yield to France all of its Adriatic territories. On 12 October Napoleon, who was in Vienna for the signature of the peace treaty, survived another assassination attempt. Whilst observing a military parade at Schönbrunn Palace, Napoleon was approached by a young man who put his hand to his coat, ready to brandish a dagger. An officer stopped him in time, and Napoleon was not even aware of what had happened. The son of a German pastor, Frédéric Staps had decided to eliminate the “tyrant” Napoleon. The Austrian defeat put an end to any hope of liberation from French dominance that the German states had. Staps was initially sentenced to death, but to avoid any patriotic popular uprising, Napoleon had him declared insane – he was however later executed.

Illustration: Vernet, “Napoleon I at the Battle of Wagram, 6 July 1809, Musée National du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)

1810 – A NEW HOPE

In December 1809, Napoleon I divorced Empress Josephine who, despite producing two children from her first marriage (Eugene and Hortense de Beauharnais), had failed to give him a son that would consolidate the Imperial regime and perpetuate the new reigning dynasty, the Bonapartes. In 1810, Napoleon engaged Tsar Alexander I on the possibility of marrying one of the Russian monarch’s sisters. When Alexander refused, Napoleon turned to his forced ‘ally’, Austria. On 1 April, he married the young Archduchess Marie-Louise Habsburg, daughter of the Emperor Francis I. A year later, on 20 March 1811, the new Empress gave birth to a son named Napoleon after his father and given the title “Roi de Rome” (King of Rome). More about the Roi de Rome.

Did you know? Marie-Louise was the grandniece of Queen Marie-Antoinette (1755-1793). Ironically, this made Napoleon the great nephew, by marriage, of Louis XVI.

Illustration: Georges Rouget, The Religious marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise, 2 April 1810 in the Salon Carré at the Louvre, © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)

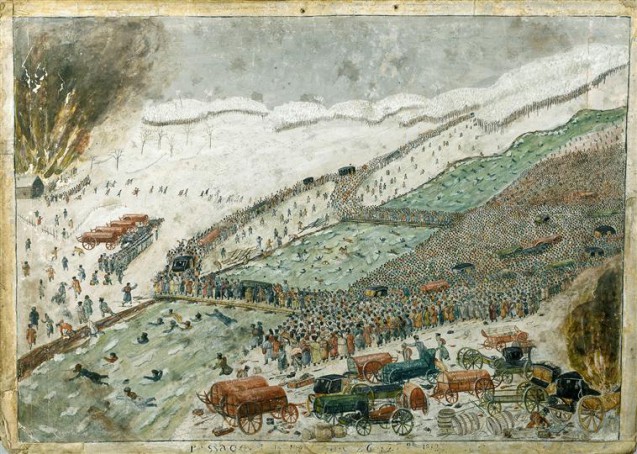

1812 – THE RUSSIAN DISASTER

The peace at Tilsit in 1807 did not prevent Franco-Russian antagonism for long. Alexander I could not accept the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw and was becoming impatient regarding war with the Ottoman Empire and its division. Taking the French annexation of the German Duchy of Oldenburg as a pretext, he declared war on 8 April 1812. In June, Napoleon invaded Russia with a force of 480,000, keeping in reserve another 120,000 soldiers. The Russian tactics centred on refusing battle, disrupting the French forces and forcing them to spread out and become dispersed.

The French easily took Vilnius and then Smolensk but on 7 September, neither Napoleon nor Koutousov emerged victorious from the battle of Borodino, at the gates of Moscow. A week later, the French entered a city soon to be consumed in flames; the Russians had sacrificed it in order to destroy any supplies or ammunition from which the French could have profited.

Napoleon thus began his retreat on 18 October. The army experienced great difficulty in crossing the swollen Berezina (a river in Belarus) 28-29 November, and Napoleon, warned of a possible coup d’état in Paris, was forced to push on ahead. He left Ney and Murat in charge of the remaining troops, but the horrendous weather conditions meant that only 20,000 soldiers returned to France alive.

Illustration : François Fournier-Sarlovèze, The French army crossing the Bérésina, 28 November 1812 © Paris – Musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais Pascal Segrette

1813 – THE BATTLE OF LEIPZIG

In 1813, as the exhausted Grande Armée returned to France from Russia, a Russo-Prussian coalition was formed. Despite two victories at Lützen on 2 May and at Bautzen on 20 May, Napoleon was defeated on 16 and 19 October at the Battle of Leipzig (known as the “Battle of the Nations” because of the number of nationalities involved – French, allied with Poles, Neapolitans, Saxons (the Kingdom of Saxony changed sides) against the Russians, Austrians, Prussians and Swedes – as well as the number of soldiers present – nearly 200,000 men on the French side, and more than 300,000 on the coalition side). Upon hearing the news of this defeat, Belgium and Holland rebelled while Austria, with the support of Murat, began re-establishing itself in Italy. And with Spain lost, France was all that remained for Napoleon.

Illustration: after Johann Adam Klein, Battle of Leipzig, 16, 18 et 19 October 1813 © Paris – Musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

1814 – THE FRENCH CAMPAIGN

After the defeat at Leipzig, English forces invaded southern France while the Prussians, Austrians and Russians threatened Paris. On 24 January 1814, Napoleon entrusted the regency to the Empress Marie-Louise and took charge of an army of 60,000 young soldiers. Despite French victories at Brienne (29 January), Champaubert (10 February) and Montmirail (11 February) in the face of much larger enemy forces, Napoleon could not prevent the invading coalition from entering Paris on 31 March 1814. When he learned of the capitulation of the capital, he made a U-turn and headed for the Chateau de Fontainebleau, the nearest Imperial residence.

On 2 April, the Senate voted in favour of deposing the Emperor, and at Fontainebleau Napoleon abdicated, in favour of his son, Napoleon II. But by 6 April, the abdication was unconditional. He was exiled to the island of Elba and Louis XVIII was restored to the Bourbon throne.

More about the French Campaign

Illustration: Delaroche, Napoleon I at Fontainebleau, 31 March 1814 © Paris – Musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

1815 – A YEAR LIKE NO OTHER

On 1 March 1815, Napoleon landed at Golfe Juan, crossed the Alps and arrived in Grenoble where an army commanded by Ney awaited him. On 20 March, Napoleon took back possession of the Palais des Tuileries, abandoned the previous day by Louis XVIII, who had fled to Belgium. Napoleon decided to pre-empt the allied forces and invaded Belgium with a force of 130,000 soldiers.

After defeating Blücher’s Prussian troops at Ligny on 16 June, he prepared for the decisive battle at Waterloo, south of Brussels. However, a combination of Ney and de Soult’s blunders, Grouchy’s failure to contain Blücher and prevent him from rejoining Wellington, and staunch English and Prussian resistance resulted in Napoleon’s defeat on 18 June. Refusing to prolong a resistance campaign, as he was advised by a number of his close associates, Napoleon capitulated on 22 June.

Did you know? During the first few months of Louis XVIII’s reign, the violet became the rallying emblem for Bonapartists. This discreet spring flower was seen as a symbol of loyalty to Napoleon and indicated a hope that a Bonaparte would return to the throne.

Illustration : after Charles de Steuben, The return from Elba © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) / Jean Schormans

1821 – THE DEATH OF NAPOLEON AT ST HELENA

On 22 June 1815, four days after the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon abdicated for the second time in his reign. He initially made for the island of Aix, from where he hoped to set sail for (possibly) the United States. At the same time, the English and French were working to prevent his escape. He eventually surrendered to British forces on 14 July; he soon learned that his captors had decided to exile him to the island of St Helena, a small isolated island in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. He was joined in exile by some of his loyal supporters: Marshal Bertrand, Count Montholon and their wives; Count de Las Cases and his young son; General Gourgaud and ten servants, including Marchand and Saint-Denis. On 17 October 1815, after a voyage of more than two months, Napoleon landed at St Helena: accessible only via a small port surrounded by tall cliffs, it was the perfect natural prison. At his residence at Longwood, originally a barn, with damp and dark rooms, Napoleon dedicated himself to dictating his memoirs. Many hours were spent, not only reliving his greatest moments, but also explaining the errors of his reign. Each day Napoleon’s health worsened due to the poor climate, a lack of privacy and the general tedium of an existence marooned on an isolated island over 2000 km from any landmass. Napoleon’s moods swung between bouts of depression, during which time he would refuse to leave Longwood, and periods of intense activity, including the conception of a new garden. His final words before his death on 5 May 1821 were of Josephine and the army.

More about Napoleon’s life in exile

Illustration : Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse, Napoleon I on his deathbed 5 May 1821 © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) / Michèle Bellot

1840 – LE RETOUR DES CENDRES

Eighteen years after the death of Napoleon in exile on the island of St Helena, with the legend of Napoleon at its apogee, King Louis-Philippe organised the return of Napoleon’s mortal remains.

On 15 December 1840, a large crowd gathered along the route of the procession. Many had not experienced life under the Empire but their imaginations had been captivated by the tales of their elders.

The funeral coach was eleven metres tall, drawn by sixteen horses, and adorned with golden caryatids supporting a display coffin. Napoleon’s actual coffin was hidden in the base of the carriage. No members of the Imperial family were able to attend the ceremony as they were still banished. The body of Napoleon now rests in the crypt of the Dome Church at Les Invalides. 100 years later, the body of his son, who died in 1832 at Schönbrunn, was interred next to Napoleon.

Did you know? In France during the 19th century, the word “cendres” (“ashes”) was systematically used to refer to a person’s mortal remains even if they had not been cremated.

Illustration : Henri-Félix-Emmanuel Philippoteaux, The return of the mortal remains of Napoleon I, Dorade arrives in Courbevoie, 14 December 1840 © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) / Daniel Arnaudet

How did Napoleon spend his time?

Find out in our Napo Factfile: A Day in the Life of Napoleon I.