What Happened to the Imperial Family in 1814?

So much of the narrative around 1814 involves the events of the French Campaign, the Adieux de Fontainebleau, the first abdication, Napoleon's exile… but what happened to those who were at the very heart of the French Empire? What happened to the Imperial family when the Emperor fell? Bringing a new perspective to 1814 in a body of original research, this article explores what key members of Bonaparte's family did before, during and after his defeat.

Joseph Bonaparte

On 28 March, faced with the advance of allied troops towards the capital, Joseph Bonaparte had urged the Empress to leave Paris. He himself escorted her as far as Blois, and then installed himself in Orléans, since it was impossible to reach Fontainebleau where he had hoped to find his brother. He wrote Napoleon a letter on 10 April, calling for the establishment of a constitutional monarchy to avoid the return of the Bourbons. This letter arrived too late: Napoleon had already abdicated. Learning this news, Joseph discretely set out for Switzerland, burying papers and diamonds close to the border. He chose as his residence the Château de Prangins, which he purchased on 12 July, and he was busying fortifying his assets in Holland and London when Napoleon returned from Elba and contacted him on 12 March 1815. It was under the threat of being taken hostage by the Allies, and with more than bountiful enthusiasm for Napoleon's return, that Joseph re-crossed the border and joined the Emperor on the road back to Paris…

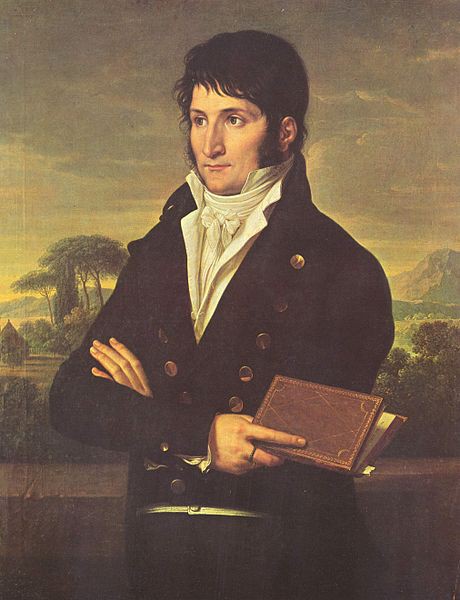

Lucien Bonaparte

refusing to renounce his second wife, Lucien Bonaparte had been banned from the Sénat (and was thus without salary) and from any mention in the list of Princes of the Imperial Family. In August 1810, he had tried, in vain, to flee to the United States, but had been stopped on his way to Sardinia by the British, who were afraid that he was colluding with his brother to conduct secret negotiations across the Atlantic. He was transferred to Malta, and from there to England, where he was interned at Thorngrove in Worcestershire. Napoleon's fall from grace liberated Lucien from this “exile”, and by 21 May 1814 he was on his way to Rome (he had spent his time in Britain working on an epic poem, Charlemagne, and studying astronomy). Pope Pius VII, who had himself just returned from captivity in France, had developed a friendship with Napoleon's brother more than ten years earlier, when he had supported the Concordat of 1801; he personally received Lucien the very day he arrived in Rome, 27 May. It was during this audience that Pius VII told Lucien of his decision to confer on him the highly coveted title of Roman prince. This news did not fail to irritate both the cardinals and French royalist circles. But Pius's benevolence was confirmed by a papal bull of 18 August 1814, which acknowledged “the loyal and sincere attachment that Lucien has always shown for the Holy See and [the Pontiff].” Thereafter Lucien sold off his properties in France and established himself definitively in Rome, where he and his wife kept a small court which proved to be a great success. However, the Hundred Days would bring new twists and turns to the tumultuous relationship between Napoleon and Lucien Bonaparte…

refusing to renounce his second wife, Lucien Bonaparte had been banned from the Sénat (and was thus without salary) and from any mention in the list of Princes of the Imperial Family. In August 1810, he had tried, in vain, to flee to the United States, but had been stopped on his way to Sardinia by the British, who were afraid that he was colluding with his brother to conduct secret negotiations across the Atlantic. He was transferred to Malta, and from there to England, where he was interned at Thorngrove in Worcestershire. Napoleon's fall from grace liberated Lucien from this “exile”, and by 21 May 1814 he was on his way to Rome (he had spent his time in Britain working on an epic poem, Charlemagne, and studying astronomy). Pope Pius VII, who had himself just returned from captivity in France, had developed a friendship with Napoleon's brother more than ten years earlier, when he had supported the Concordat of 1801; he personally received Lucien the very day he arrived in Rome, 27 May. It was during this audience that Pius VII told Lucien of his decision to confer on him the highly coveted title of Roman prince. This news did not fail to irritate both the cardinals and French royalist circles. But Pius's benevolence was confirmed by a papal bull of 18 August 1814, which acknowledged “the loyal and sincere attachment that Lucien has always shown for the Holy See and [the Pontiff].” Thereafter Lucien sold off his properties in France and established himself definitively in Rome, where he and his wife kept a small court which proved to be a great success. However, the Hundred Days would bring new twists and turns to the tumultuous relationship between Napoleon and Lucien Bonaparte…

Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi

Élisa Bonaparte Baciocchi, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Napoleon's eldest sister, fled hers. She left Florence on 1 February 1814 to a chorus of jeers, shortly before British troops began to land in Livorno. Although the French Campaign was raging and the Empire was crumbling around it, Élisa tried throughout February to save Elba for Napoleon, ordering General Dalesme to defend the island at all costs. Threatened herself by the advance of the Austrian and British forces, Élisa was forced to leave Lucca on 13 March, first in the direction of Genoa, then, learning of the allied presence in Lyon, rerouting to Montpellier, where she and her husband, Felice Pasquale Baciocchi, arrived ten days later. Pregnant and exhausted by this flight, Élisa made a halt in Montpellier, at the Château de la Piscine: it was here that she learned of the capitulation of Paris, while visiting the city's botanical gardens. Faced with hostility from the people of Montpellier, the fallen emperor's sister was again forced to flee, disguised in a post-chaise. She travelled to Aix, and then on 15 April to Marseille, writing en route by turns to Fouché, Talleyrand, the Tsar, and finally to Metternich in the hope of consolidating her position. On 13 May, the Comte de Ségur confirmed the inevitable: Metternich refused to allow her to keep Lucca. Élisa went on throughout the summer to plead her case in Vienna and then in Graz, where she stayed with her brother Jerome, who had become Prince of Montfort, but she received nothing more from Metternich than a passport for Italy. Felice Baciocchi had taken the lead and installed himself in Bologna to secure the remains of their fortune, the majority of which had been sequestered by the Austrian commander in Lucca. On 10 August, on the return journey from Graz to Bologna, Élisa gave birth to a son, Jerome-Frédéric-Felice-Napoleon. Shortly afterwards she travelled to Trieste, to assist in her sister-in-law Catherine's birth in turn. Hoping to attract the benevolence of the Austrians, Élisa limited herself to a modest lifestyle at the Villa Caprara in Bolonga… She had almost succeeded, but then her illustrious brother made his dramatic return to France, and Élisa was arrested and sent under surveillance to Austria.

Élisa Bonaparte Baciocchi, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Napoleon's eldest sister, fled hers. She left Florence on 1 February 1814 to a chorus of jeers, shortly before British troops began to land in Livorno. Although the French Campaign was raging and the Empire was crumbling around it, Élisa tried throughout February to save Elba for Napoleon, ordering General Dalesme to defend the island at all costs. Threatened herself by the advance of the Austrian and British forces, Élisa was forced to leave Lucca on 13 March, first in the direction of Genoa, then, learning of the allied presence in Lyon, rerouting to Montpellier, where she and her husband, Felice Pasquale Baciocchi, arrived ten days later. Pregnant and exhausted by this flight, Élisa made a halt in Montpellier, at the Château de la Piscine: it was here that she learned of the capitulation of Paris, while visiting the city's botanical gardens. Faced with hostility from the people of Montpellier, the fallen emperor's sister was again forced to flee, disguised in a post-chaise. She travelled to Aix, and then on 15 April to Marseille, writing en route by turns to Fouché, Talleyrand, the Tsar, and finally to Metternich in the hope of consolidating her position. On 13 May, the Comte de Ségur confirmed the inevitable: Metternich refused to allow her to keep Lucca. Élisa went on throughout the summer to plead her case in Vienna and then in Graz, where she stayed with her brother Jerome, who had become Prince of Montfort, but she received nothing more from Metternich than a passport for Italy. Felice Baciocchi had taken the lead and installed himself in Bologna to secure the remains of their fortune, the majority of which had been sequestered by the Austrian commander in Lucca. On 10 August, on the return journey from Graz to Bologna, Élisa gave birth to a son, Jerome-Frédéric-Felice-Napoleon. Shortly afterwards she travelled to Trieste, to assist in her sister-in-law Catherine's birth in turn. Hoping to attract the benevolence of the Austrians, Élisa limited herself to a modest lifestyle at the Villa Caprara in Bolonga… She had almost succeeded, but then her illustrious brother made his dramatic return to France, and Élisa was arrested and sent under surveillance to Austria.

Hortense de Beauharnais and Louis Bonaparte

Hortense for her part hesitated before accepting the defeat and leaving for Rambouillet. It was there that she learned from Joseph and Jerome that Paris had capitulated. On 1 April, she headed further west to join her mother who had fled to her Château de Navarre near Evreux. Mother and daughter were there to learn that the Senate had deposed Napoleon. At this point we know that Hortense briefly considered retiring to her mother's estates on Martinique (so she wrote in a letter dated 9 April to her Lectrice and confidante). However, taking advice from her mother, she returned to Malmaison, entrusting herself to the goodwill of the Tsar Alexander I. On 30 May, Louis XVIII bowed to pressure from Alexander and granted the ex-Queen of Holland the duchy of Saint-Leu and annual a pension of 400,000 Francs, a solution that had been agreed with Napoleon at Fontainebleau. Cold comfort however, since Hortense had just lost her mother. The new Duchesse de Saint-Leu was soon to be separated from her brother, who (halfway through June) headed to Bavaria to stay with his father-in-law. Alone in France, Hortense attended first to her own health, going on 25 July to Plombières to take the waters, leaving her sons at Saint-Leu. This essentially political gesture aimed at preventing her property from being confiscated and at showing that she trusted the new regime. Heading to Baden to meet her brother (she stayed there from 10 to 29 August), she then returned to France, to take the sea air at Le Havre up to 15 September. At the end of the month, the head of her husband's Cabinet Topographique, Briatte, informed Hortense that Louis was in Rome (Italy) and that he demanded that his sons join him. Hortense refused, and a court case loomed. Hortense was above all concerned that her sons should have a future in a restored France. And so in order to quash rumours of her participation in conspiracies against the king, she demanded and received an audience on 2 October. Reassured as to king's opinion of her, she moved to the Faubourg Saint-Germain (Paris). She was still living there when Napoleon landed at Golfe Juan almost a year later…

Hortense for her part hesitated before accepting the defeat and leaving for Rambouillet. It was there that she learned from Joseph and Jerome that Paris had capitulated. On 1 April, she headed further west to join her mother who had fled to her Château de Navarre near Evreux. Mother and daughter were there to learn that the Senate had deposed Napoleon. At this point we know that Hortense briefly considered retiring to her mother's estates on Martinique (so she wrote in a letter dated 9 April to her Lectrice and confidante). However, taking advice from her mother, she returned to Malmaison, entrusting herself to the goodwill of the Tsar Alexander I. On 30 May, Louis XVIII bowed to pressure from Alexander and granted the ex-Queen of Holland the duchy of Saint-Leu and annual a pension of 400,000 Francs, a solution that had been agreed with Napoleon at Fontainebleau. Cold comfort however, since Hortense had just lost her mother. The new Duchesse de Saint-Leu was soon to be separated from her brother, who (halfway through June) headed to Bavaria to stay with his father-in-law. Alone in France, Hortense attended first to her own health, going on 25 July to Plombières to take the waters, leaving her sons at Saint-Leu. This essentially political gesture aimed at preventing her property from being confiscated and at showing that she trusted the new regime. Heading to Baden to meet her brother (she stayed there from 10 to 29 August), she then returned to France, to take the sea air at Le Havre up to 15 September. At the end of the month, the head of her husband's Cabinet Topographique, Briatte, informed Hortense that Louis was in Rome (Italy) and that he demanded that his sons join him. Hortense refused, and a court case loomed. Hortense was above all concerned that her sons should have a future in a restored France. And so in order to quash rumours of her participation in conspiracies against the king, she demanded and received an audience on 2 October. Reassured as to king's opinion of her, she moved to the Faubourg Saint-Germain (Paris). She was still living there when Napoleon landed at Golfe Juan almost a year later…

Eugène de Beauharnais

temporary victory over the allies on the river Mincio on 9 February 1814, Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy, was at an impasse. At the same time as Murat opened negotiations with Austria in order to save his own throne in Naples, Eugène was faced with similar pressure from the Allies. Added to this was the order from the Emperor in mid-March to leave Italy in order to lend support to the struggle in Champagne. Despite the fact that Eugène ignored this order, Napoleon (fully aware that Eugène was following his own path) nevertheless was to request at the Congress of Châtillon that his stepson should retain his position in Italy, something that Austria categorically refused. Eugène was in Mantua during the taking of Paris and Napoleon's abdication. At the beginning of April, he received letters from his father-in-law, the King of Bavaria, and from his mother, Josephine, the latter telling him to “look to his family” and distance himself from Napoleon. On 16 April Eugène agreed to sign a convention presented by the Austrian emissary Neipperg, under the misapprehension that he would be able to keep control of Milan. It was only when, on 20 April, his Finance Minister Prina was lynched by the mob in the city that the Viceroy of Italy finally realised the extent of Italian enmity for the French occupier in Milan. On 23 April, Eugène signed a new convention agreeing his withdrawal with Austria, whom he had asked for protection. A secret article guaranteed him the protection of his personal wealth. Eugène set out for his father-in-law's territories on 26 April; arriving in Munich at the beginning of May, he departed almost immediately for Paris, where the Allies were assembled, in order to fight for the 'appropriate treatment' that Article VI of the Treaty of Fontainebleau had provided for him. Louis XVIII received Eugène cordially, but no real results came from his pretensions. Writing to Napoleon on 25 May, he informed his stepfather that he was resigned to await 'peaceably the fate that the allied powers would be pleased to grant [him].' At the end of May he was preparing to return to Munich when he learned of his mother's failing health. He was at her bedside with his sister when the former Empress passed away on 28 May. Eugène and Hortense, supported in their grief by Tsar Alexander I, spent several days together in the house established for Hortense in Saint-Leu. This mark of friendship reassured the former Viceroy of Italy when he took the road to Bavaria on 11 June. He would never again set foot in France.

temporary victory over the allies on the river Mincio on 9 February 1814, Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy, was at an impasse. At the same time as Murat opened negotiations with Austria in order to save his own throne in Naples, Eugène was faced with similar pressure from the Allies. Added to this was the order from the Emperor in mid-March to leave Italy in order to lend support to the struggle in Champagne. Despite the fact that Eugène ignored this order, Napoleon (fully aware that Eugène was following his own path) nevertheless was to request at the Congress of Châtillon that his stepson should retain his position in Italy, something that Austria categorically refused. Eugène was in Mantua during the taking of Paris and Napoleon's abdication. At the beginning of April, he received letters from his father-in-law, the King of Bavaria, and from his mother, Josephine, the latter telling him to “look to his family” and distance himself from Napoleon. On 16 April Eugène agreed to sign a convention presented by the Austrian emissary Neipperg, under the misapprehension that he would be able to keep control of Milan. It was only when, on 20 April, his Finance Minister Prina was lynched by the mob in the city that the Viceroy of Italy finally realised the extent of Italian enmity for the French occupier in Milan. On 23 April, Eugène signed a new convention agreeing his withdrawal with Austria, whom he had asked for protection. A secret article guaranteed him the protection of his personal wealth. Eugène set out for his father-in-law's territories on 26 April; arriving in Munich at the beginning of May, he departed almost immediately for Paris, where the Allies were assembled, in order to fight for the 'appropriate treatment' that Article VI of the Treaty of Fontainebleau had provided for him. Louis XVIII received Eugène cordially, but no real results came from his pretensions. Writing to Napoleon on 25 May, he informed his stepfather that he was resigned to await 'peaceably the fate that the allied powers would be pleased to grant [him].' At the end of May he was preparing to return to Munich when he learned of his mother's failing health. He was at her bedside with his sister when the former Empress passed away on 28 May. Eugène and Hortense, supported in their grief by Tsar Alexander I, spent several days together in the house established for Hortense in Saint-Leu. This mark of friendship reassured the former Viceroy of Italy when he took the road to Bavaria on 11 June. He would never again set foot in France.

Madame Mère and Pauline Bonaparte

late 1813, Murat had sided with the Austrians, hoping to keep hold of his kingdom of Naples or even to stir up a revolutionary movement in Italy of which he could be the head, to the detriment of both Eugène and Napoleon's son, the Roi de Rome. Encouraged down this path by his wife Caroline Bonaparte, Murat tried to consolidate the treaty that had been laid out with the Austrian Empire on 11 January 1814: it, at least on paper, guaranteed him his throne, some 400,000 subjects, and sums of money, though these agreements, which were also sent to his former enemies and their intemediaries (Fouché, Talleyrand, and the future Louis XVIII), were to in fact remain a dead letter. Supporting her husband in every way, Caroline also tried a little “damage control” to limit the effects of the fall of her family on her own future with various delaying tactics: she sent 30,000 francs to Cardinal Fesch, reprimanded Lucien for the appearance of his Charlemagne and its charges against Napoleon, and tried to reconcile with Madame Mère by sending her horses. It was a different story with the new occupant of Elba, with whom contact was officially cut: Napoleon's request to the Kingdom of Naples for a chef and a decorator was refused, and the Neapolitan consul in Portoferraio was recalled. All too aware that he was being watched by the Austrians, who only wanted one false move on his part to renege on the entire treaty, Murat denied in the official press on 27 August the existence of any secret talks between Naples and Elba. In fact, by September the situation showed a real ambivalence on the part of the Murats towards Napoleon: on 9 September, Napoleon received birthday wishes from the King of Naples, but on 15 September, Murat confiscated the allowances he was paying to the Dukes of Reggio, Gaète and Otrante, as well as those for the Comte Régnier and Alexandre Walewski (Murat would restore Walewski's payments a few weeks later when Maria Walewska arrived in Naples). Could Pauline Bonaparte, who was going back and forth between the two kingdoms, have served as an oral intermediary between Napoleon and Murat? The British and the Austrians who were spying on both were absolutely convinced of it, and so was d'Anglès, Louis XVIII's Chief of Police. On Saint Helena, Napoleon was to deny all secret relations, though as history has now shown us, this was being slightly economical with the truth. In his memoirs, Napoleon “denied all communication with the King of Naples […] Leaving for France, he wrote that, on retaking his throne, he was delighted to declare that he would let bygones be bygones, and that he would pardon [Murat's] previous conduct, offering him his goodwill, and to send someone to sign a guarantee for his states, and he recommended to him above all to remain on good terms with the Austrians, and to maintain these good relations in the case that the Austrians were to march on France.” This retrospective presentation of the facts was evidently made in full knowledge of the very different destiny that awaited Murat in 1815…

late 1813, Murat had sided with the Austrians, hoping to keep hold of his kingdom of Naples or even to stir up a revolutionary movement in Italy of which he could be the head, to the detriment of both Eugène and Napoleon's son, the Roi de Rome. Encouraged down this path by his wife Caroline Bonaparte, Murat tried to consolidate the treaty that had been laid out with the Austrian Empire on 11 January 1814: it, at least on paper, guaranteed him his throne, some 400,000 subjects, and sums of money, though these agreements, which were also sent to his former enemies and their intemediaries (Fouché, Talleyrand, and the future Louis XVIII), were to in fact remain a dead letter. Supporting her husband in every way, Caroline also tried a little “damage control” to limit the effects of the fall of her family on her own future with various delaying tactics: she sent 30,000 francs to Cardinal Fesch, reprimanded Lucien for the appearance of his Charlemagne and its charges against Napoleon, and tried to reconcile with Madame Mère by sending her horses. It was a different story with the new occupant of Elba, with whom contact was officially cut: Napoleon's request to the Kingdom of Naples for a chef and a decorator was refused, and the Neapolitan consul in Portoferraio was recalled. All too aware that he was being watched by the Austrians, who only wanted one false move on his part to renege on the entire treaty, Murat denied in the official press on 27 August the existence of any secret talks between Naples and Elba. In fact, by September the situation showed a real ambivalence on the part of the Murats towards Napoleon: on 9 September, Napoleon received birthday wishes from the King of Naples, but on 15 September, Murat confiscated the allowances he was paying to the Dukes of Reggio, Gaète and Otrante, as well as those for the Comte Régnier and Alexandre Walewski (Murat would restore Walewski's payments a few weeks later when Maria Walewska arrived in Naples). Could Pauline Bonaparte, who was going back and forth between the two kingdoms, have served as an oral intermediary between Napoleon and Murat? The British and the Austrians who were spying on both were absolutely convinced of it, and so was d'Anglès, Louis XVIII's Chief of Police. On Saint Helena, Napoleon was to deny all secret relations, though as history has now shown us, this was being slightly economical with the truth. In his memoirs, Napoleon “denied all communication with the King of Naples […] Leaving for France, he wrote that, on retaking his throne, he was delighted to declare that he would let bygones be bygones, and that he would pardon [Murat's] previous conduct, offering him his goodwill, and to send someone to sign a guarantee for his states, and he recommended to him above all to remain on good terms with the Austrians, and to maintain these good relations in the case that the Austrians were to march on France.” This retrospective presentation of the facts was evidently made in full knowledge of the very different destiny that awaited Murat in 1815…

Jerome Bonaparte

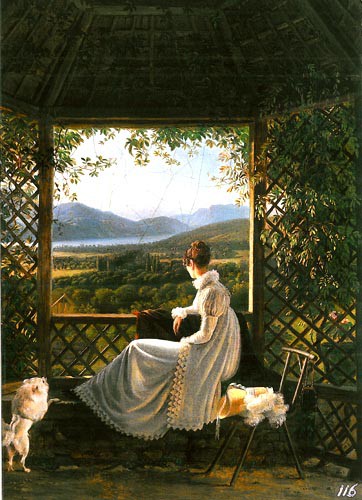

Jerome, former king of Westphalia, had opposed Empress Marie-Louise's departure for Rambouillet on 29 March 1814 when Paris was threatened by the Allies. He grudgingly followed her after the capitulation, in spite of Napoleon's order that he travel to Brittany. And although Jerome tried to force his sister-in-law to stay, he was not forgetful of his own interests: on 8 April, he therefore drew his salary for his service to the state and also the million Francs that the fallen Emperor had ordered to be paid two days earlier, matching the sums given to Joseph, Louis, Pauline, Elisa and Madame Mère. Jerome was hoping, in fact, for help from his father- and brother-in-law, the King and Prince Royal of Württemberg. His wife Catherine of Württemberg, who had remained with him in Paris since Blois, asked her family for asylum in Stuttgart on 8 April, but they refused. The Tsar, however, provided them with a passport and the former royal couple of Westphalia planned to meet up again in Switzerland. Catherine set out with their fortune, but her carriage was ambushed on 21 April by the adventurer and royalist the Comte de Maubreuil, which slowed her progress and cleaned out their kitty. In spite of the Tsar's support, she never recovered the stolen chests of jewels, which Jerome regretted bitterly, since he had wanted to continue to live in the manner to which he had become accustomed and to which he believed he had the right. The couple were eventually reunited on 30 April and, faced with the persistent refusal of Catherine's family to accommodate them, they accepted the Austrian Empire's offer to house them in Graz, in Eckensberg, from mid-June. Jerome still nursed political dreams and planned to follow his sister Elisa, who visited him at the end of July, to Bologna where he hoped to obtain control of that Papal Legation. It was precisely because of these aspirations that Metternich sent a refusal to Jerome and proposed rather to install him in Trieste, an Austrian territory, where there were already a number of French émigrés. Arriving in Trieste on 20 August, Jerome and Catherine welcomed another happy arrival: their son, Jerome Napoleon Charles, was born on 24 August. Whilst his wife's labour had been difficult, Jerome too was having a similarly ‘bitter birth', namely the realization that he would never receive any land from the Allies. No difficulty, then, in understanding his eagerness to join Napoleon during the Hundred Days.

Jerome, former king of Westphalia, had opposed Empress Marie-Louise's departure for Rambouillet on 29 March 1814 when Paris was threatened by the Allies. He grudgingly followed her after the capitulation, in spite of Napoleon's order that he travel to Brittany. And although Jerome tried to force his sister-in-law to stay, he was not forgetful of his own interests: on 8 April, he therefore drew his salary for his service to the state and also the million Francs that the fallen Emperor had ordered to be paid two days earlier, matching the sums given to Joseph, Louis, Pauline, Elisa and Madame Mère. Jerome was hoping, in fact, for help from his father- and brother-in-law, the King and Prince Royal of Württemberg. His wife Catherine of Württemberg, who had remained with him in Paris since Blois, asked her family for asylum in Stuttgart on 8 April, but they refused. The Tsar, however, provided them with a passport and the former royal couple of Westphalia planned to meet up again in Switzerland. Catherine set out with their fortune, but her carriage was ambushed on 21 April by the adventurer and royalist the Comte de Maubreuil, which slowed her progress and cleaned out their kitty. In spite of the Tsar's support, she never recovered the stolen chests of jewels, which Jerome regretted bitterly, since he had wanted to continue to live in the manner to which he had become accustomed and to which he believed he had the right. The couple were eventually reunited on 30 April and, faced with the persistent refusal of Catherine's family to accommodate them, they accepted the Austrian Empire's offer to house them in Graz, in Eckensberg, from mid-June. Jerome still nursed political dreams and planned to follow his sister Elisa, who visited him at the end of July, to Bologna where he hoped to obtain control of that Papal Legation. It was precisely because of these aspirations that Metternich sent a refusal to Jerome and proposed rather to install him in Trieste, an Austrian territory, where there were already a number of French émigrés. Arriving in Trieste on 20 August, Jerome and Catherine welcomed another happy arrival: their son, Jerome Napoleon Charles, was born on 24 August. Whilst his wife's labour had been difficult, Jerome too was having a similarly ‘bitter birth', namely the realization that he would never receive any land from the Allies. No difficulty, then, in understanding his eagerness to join Napoleon during the Hundred Days.