Abstract

Cultural intelligence preparation of the battle space (IPB), with a focus on the post-hostilities landscape is as important, if not more so, than traditional intelligence preparation of the battle space, which has historically monopolized the intelligence effort. Contemporary challenges in post-hostilities Iraq have several parallels with Napoleon's disastrous campaign on the Iberian Peninsula nearly two centuries ago. Alone and in concert, these campaigns highlight that an inordinate focus on armies to the detriment of a proper focus on the people has, and will continue to make, winning the peace infinitely more difficult than winning the war.

If political objectives are to be achieved, the U. S. military must accept the fact that the post-hostilities environment is central to campaign design. Preventing the emergence of a strategic gap between decisive combat operations and the immediate requirement to perform stability and support operations lies squarely on the shoulders of the joint and/or combined force and must be intelligence driven.

Bridging the cultural intelligence gap will require three steps: The first is the acceptance that that history is important and the recognition that it holds clues that will shed light on cultural intelligence requirements. The second step should be a culturally-oriented addition to the intelligence series within joint doctrine, focused on “the people”. The third step builds on the previous two and stresses holistic backward planning that achieves intelligence leverage in the post-hostilities phase of a campaign.

The U. S. Joint Forces Command, tasked with the lead for Transformation within the Department of Defense, has taken a first step in placing more emphasis on cultural intelligence and the imperative of understanding a country's or region's dynamics well beyond fielded forces or other potential combatants. The Draft Stability Operations Joint operating Concept focuses on the vital period within a campaign that follows large-scale combat operations. As importantly, this concept stresses the requirement for a people-oriented intelligence focus.

Still, the “gravitational pull” of ever-improving technology coupled with the drive toward “Transformation” has resulted in the adoption of a mindset that more can be done with less to achieve the decisive effects in recent and futures campaigns. In certain aspects of campaign planning, increased efficiency and effectiveness resulting from technological breakthroughs lends credence to this line of thinking. However, policymakers, commanders and planners alike must be ever mindful that efficiency should not be held up as the overarching goal at the expense of better understanding.

If we are to apply Napoleon's maxim that “The moral is to the physical as three to one” within a truly holistic campaign design, then perhaps such a ratio should be applied in balancing the collective intelligence effort, with a focus on the people assuming paramount importance. Technology is not a panacea within our joint war fighting construct, and especially across the spectrum of intelligence requirements. As the world becomes even more complex, it is critical to understand root causes and effects of histories and cultures of the peoples with whom the joint force will interact. Relying less on high-tech hardware, such a mental shift may be the most transformational step the military can take in preparing for the challenges of the 21st Century.

Chapter 1: Genesis of an ulcer

Not a Frenchman then doubted that such rapid victories must have decided the fate of the Spaniards. We believed, and Europe believed it too, that we had only to march to Madrid to complete the subjection of Spain and to organize the country in the French manner, that is to say, to increase our means of conquest by all the resources of our vanquished enemies. The wars we had hitherto carried on had accustomed us to see in a nation only its military forces and to count for nothing the spirit which animates its citizens. (1) – a Swiss soldier serving in Napoleon's army, 1808

Nearly two centuries ago, Napoleon pre-emptively occupied Portugal and Spain and ousted the Spanish royal family for being less than cooperative in their support toward his Continental System. As Napoleon proclaimed, “Spaniards, your nation is perishing after a long agony; I have seen your ills, I am about to bring to you the remedy for them,” never did he imagine that that conflict would continue in an altogether different form. (2)

The introduction of what was for the first time classified as “guerrilla war,” or “little war” as it was first expressed by the Spanish, was incomprehensible within Napoleon's conventional military mindset. The resulting resistance, as described by Martin van Creveld, “made do without ‘armies', campaigns, battles, bases, objectives, external and internal lines, points d'appui, or even territorial units clearly separated by a line on a map”, (3) Napoleon's “Spanish Ulcer”, as he chose to describe the Spanish response to his occupation, provides a myriad of timeless lessons for strategic and operational planners. The strategic gap that developed between Napoleon's rapid conventional military victory and the immediate requirement to positively influence the population as part of post-hostilities stabilization operations serves to highlight the limits of conventional military power in post-conflict operations and the perils of forgetting “the people” in the initial and ongoing strategic calculus.

Unfortunately, nations and militaries around the globe have been forced to re-learn that lesson many times in the ensuing two hundred years.

The parallels between Napoleon's challenges in Spain and contemporary challenges for coalition forces in Iraq are striking. While there is, undoubtedly, a danger in attempting to draw historical parallels too far, some similarities are too close to ignore. Moreover, such similarities may reflect the failure to adequately understand the local populace within campaign planning. That understanding forms the bedrock for any successful post-hostility occupation place.

Thus cultural intelligence preparation of the battle space (IPB), with a focus on the post-hostilities landscape is as important, if not more so, than traditional intelligence preparation of the battle space, which has historically monopolized the intelligence effort. Countless historical lessons resemble Napoleon's experience against popular Spanish resistance and provide clear insight as to what should comprise the proper balance of effort within intelligence preparation for armed intervention. These lessons repeatedly demonstrate that an inordinate focus on armies to the detriment of a proper focus on the people has, and will continue to make, winning the peace infinitely more difficult than winning the war. Ultimately, closing the cultural intelligence gap by striking an IPB balance within campaign planning may reduce surprises for an occupying force that historically have impeded the accomplishment of the campaign's stated political/grand strategic objectives.

Chapter 2: The Spanish resistance – a historical example

I thought the system easier to change than it has proved in that country, with its corrupt minister, its feeble king and its shameless, dissolute queen. (4) – Napoleon on the occupation of Spain

Napoleon gave little thought toward potential challenges of occupying Spain in 1808 once his army had completed what he believed would be little more than a “military promenade”. (5) Conditioned by the results and effects of his overwhelmingly decisive military victories at Austerlitz (1805) and Jena (1806), Napoleon clearly envisioned that the occupation of major Spanish cities and the awarding of the Spanish throne to his older brother Joseph would close the Iberian chapter in his quest for domination of the continent.

The “ulcer of resistance”, which flared up with varying degrees of intensity throughout the country, was most intense in the territory of Navarre and surrounding northern provinces. (6) That diamond-shaped area, which stretched just less than 100 miles from north to south and about 75 miles from east to west, proved to be the hub of Spanish resistance. (7) A closer examination of the people who inhabited that region uncovers numerous clues why resistance to a foreign occupier was so ferocious and ultimately weighed heavily in the defeat of Napoleon in Spain. More importantly, it highlights the importance of analysis of the Spanish people, their history, culture, motivations, and their potential to support or hinder efforts at achieving French political objectives.

Author John Tone, in his recently published The Fatal Knot, succinctly describes the macro-conditions for guerrilla resistance in northern Spain:

“The English blockade of Spain and Spanish America after 1796 had curtailed the option of emigrating to America, and the economic contraction caused by the blockade made work in Madrid and Ribera more difficult to find as well. What the French found in the Montaña in 1808, therefore, was densely populated, rugged country full of young men with no prospects. Thus, the availability of guerrillas was the result in part, of a particular economic and demographic conjuncture in the Montaña.” (8)

As a whole, the Spanish and Portuguese “were inured to hardship, suspicious of foreigners and well versed in the ways of life – above all, banditry and smuggling – that were characterized by violence and involved constant skirmishes with the security forces”. (9) Unknown to Napoleon and his marshals, on the heels of yet another impressive military rout, there bubbled under the surface a “popular patriotism, religious fanaticism and an almost hysterical hatred for the French”. (10)

The lack of influence of Spanish central authority over its citizenry proved surprising to Napoleon and his marshals, as their point of reference was the occupation of northern European countries. There they found the “Germans and Austrians, conditioned by militarism and centralization, unable or unwilling to act without the permission of their superiors”. (11) A common complaint emanating from the French as they grappled with occupying such an independent and spirited Spanish citizen was that:

“Spain was at least a century behind the other nations of the continent. The insular situation of the country and the severity of its religious institutions had prevented the Spaniards from taking part in the disputes and controversies which had agitated and enlightened Europe.” (12)

Cultural “mirror-imaging” left the French blind to the reality that many Spanish provinces had never been accountable to the royal edicts emanating from Madrid – many Spaniards commonly displayed open contempt for policy disbursed from their national government. Given such an environment of such regional independence and domestic political tension, Spaniards even more virulently “disdained anything done for them by a foreigner”. (13)

This was especially true in Navarre where its citizens, imbued with a strong allegiance to local government and long appeased by national officials in Madrid in an effort to retain a modicum of control, enjoyed perquisites not common throughout the rest of the country.

“One of Navarre's most valuable privileges was its separate customs borders. In a rest of Spain, the Bourbons had created a single, national market, and they had restricted the importation of finished manufactured goods and the exportation of raw materials in an attempt to encourage industrial development. Navarre, however controlled its own borders and was exempt from these restrictions.” (14)

A modicum of cultural intelligence preparation by the French prior to their occupation of Spain might have indicated that the Navarrese stood apart from many of their countrymen in their relative freedom, and therefore would have the most to lose under French occupation. Succinctly put, the Navarrese owed much of their existence to the smuggling of French goods into Spain, avoiding any central government. (15) Any cultural analysis should have revealed that assuming new fiscal duties towards an occupying power would be economically ruinous and psychologically offensive to the Navarrese.

The economic factor within the Spanish resistance assumed added significance due to the scattering of Spanish soldiers in the wake of Napoleon's military juggernaut.

Dispersed soldiers, no longer sustained by even their paltry military income, were left to roam the countryside focusing simply on survival.

“With the French imposing strict limits on movement and clamping down on many traditional aspects of street life, opportunities to find alternative sources of income were limited, and all the more so as industry was at a standstill and many senores unable to pay their existing retainers and domestic servants . Let alone take on fresh hands. In short, hunger and despair reigned on all sides.” (16)

In such a desperate environment, many young men, former soldiers and civilians alike, were driven into the guerrilla fold out of sheer economic necessity, thus exacerbating a pre-existing patriotic fervor that emanated from northern Spain and which was further fuelled by French occupation.

Napoleon also greatly underestimated the strong influence of the Catholic Church on the Spanish people. The Church served to energize the notion of an ideological struggle. Ecclesiastical leaders of guerrilla bands were expert at intertwining a host of reasons to continue the struggle against the French. Sebastian Blaze, an officer in Napoleon's army, described the power of the Church:

“The monks skilfully employed the influence which they still enjoyed over Spanish credulity… to inflame the populace and exacerbate the implacable hatred with which they already regarded us… In this fashion they encouraged a naturally cruel and barbarous people to commit the most revolting crimes with a clear conscience. They accused us of being Jews, heretics, sorcerers… As a result, just to be a Frenchman became a crime in the eyes of the country.” (17)

In the final analysis, “The Spaniards might not have liked their rulers, but they regarded them as preferable to some imposed, foreign dictator. Napoleon could establish Joseph on the Throne, but he could not give him popular support”. (18)

Napoleon's cultural miscalculation resulted in a protracted struggle of occupation that lasted nearly six years and ultimately required approximately three-fifths of the Empire's total armed strength, almost four times the force of 80,000 Napoleon originally had designated for this duty. (19) The sapping of the Empire's resources and energy in countering the Spanish resistance had far-reaching implications and proved to be the beginning of the end for Napoleon. A new type of warfare, with which Napoleon was wholly unfamiliar, was rooted in the people and drove a wedge, the “decisive gap”, between conventional military victory and the achievement of his strategic design.

As David Chandler wrote in The Campaigns of Napoleon “Napoleon the statesman had set Napoleon the soldier an impossible task. Consequently, although the immediate military aims were more or less achieved, the long-term requirement of winning popular support for the new regime was hopelessly compromised. The lesson was there for the world to read: military conquest in itself cannot bring about political victory.” (20)

French grand strategic victory required an understanding as to what winning popular support of the Spanish people actually entailed. In that Napoleon demonstrated almost complete ignorance. Unfortunately for the French emperor, the realities of his tragic oversight were not fully comprehended until long after conventional combat operations had ceased and various elements of the Spanish population had seized the initiative.

Chapter 3: A preventable "Iraqi ulcer"

“There is nothing new about the failure to give conflict termination the proper priority. The history of warfare is generally one where the immediate needs of warfighting, tactics and strategy are given priority over grand strategy. Conflict termination has generally been treated as a secondary priority, and the end of was has often been assumed to lead to a smooth transition to peace or been dealt with in terms of vague plans and ideological hopes.” (21) – Anthony Cordesman, Center for Strategic and International Studies

The aftermath of U.S.-led decisive combat operations in Operation IRAQI FREEDOM has presented challenges to coalition forces similar to those experienced by the Napoleonic army in Spain almost two centuries ago. Unquestionably, the French harsh treatment of the Spanish citizenry was much different than that of the coalition's toward the Iraqi people. Thus a parallel cannot be drawn in the treatment of the Spanish and Iraqi peoples.

However, the shared failure to adequately understand the respective peoples and cultures stands in bold relief. The French experience in Spain, as well those of army other nations in the intervening two hundred years should drive us to examine why we are prone to making centuries-old mistakes in our campaign planning.

General Anthony Zinni, a former commander of U. S. Central Command, remarked on the formulation of a coherent campaign design, “We need to talk about not how you win the peace as a separate part of the war, but you have to look at this thing from start to finish. It is not a phased conflict; there is not a fighting part and then another part. It is a nine-inning game.” (22)

In planning for Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, the coalition was unable to focus its intelligence effort toward the challenges of post-hostilities arguably until it was too late to be decisive in the strategically critical period between the end of large-scale combat and the wholesale transition to stability and support operations. Planning for post-hostility operations was conducted almost completely in the blind at the tactical and operational levels with only scattered intelligence on the Iraqi people, specifically, what their likely reception of an occupying force might be, and where the coalition might continue to face resistance.

Planners did possess the macro-level detail of the ethnic and religious divisions and the historical tensions between the various religious and ethnic groups, specifically the Sunnis, Shias, and Kurds. But, that cultural understanding did not have the fidelity to highlight that, for example, “more than 75 percent of Iraqi belong to one of 150 tribes, and that significant numbers of Iraqis subscribe to many of the medieval conventions of Islamic law, from unquestioning obedience to tribal elders, polygamy, and revenge-killings to blood money paid to the relatives of persons killed in feuds”. (23) Nor did the coalition understand the true depth of influence of the leading Shia cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani or the young firebrand, Muqtada al-Sadr.

Furthermore, little analysis was conducted which highlighted what segment of the Iraqi population was likely to experience the highest degree of disenfranchisement.

Little intelligence analysis oriented on the stabilization phase took into account the prospect of large segments of the Iraqi Republican Guard, Special Republican Guard, and remnants of the Ba'athist security apparatus scattered throughout the middle part of the country with no employment and a perceived less-than-bright future within an occupied Iraq. In other words there was insufficient intelligence focused on the people vice fielded forces and the regime's security apparatus in a post-hostilities scenario.

A broad cultural intelligence analysis, for example, could have drawn-out the historical parallel between the Iraqi “Sunni Triangle” and the Spanish “Navarrese Diamond,” assuming, of course, that members of the analysis team were also familiar with the cultural factors that contributed to Napoleon's “Spanish Ulcer.” With that parallel in mind and despite the full benefit of hindsight, few would argue with Anthony Cordesman's assessment in his The Lessons of the Iraq War.

“The intelligence community exaggerated the risk of a cohesive Ba'ath resistance in Baghdad, the Sunni triangle, and Tikrit during the war, and was not prepared to deal with the rise of a much more scattered and marginal resistance by Ba'ath loyalists after the war. The intelligence effort was not capable of distinguishing which towns and areas were likely to be a source of continuing Ba'athist resistance and support.” (24)

The U.S.–led planning effort expended the better part of 16 months determining how best to “break humpty-dumpty” with little timely thought that the Coalition might be charged with “putting him back together again.” The later task, infinitely more difficult and foreign to the joint force than those associated with conventional combat operations and with the Iraqi people squarely at the center of such a planning challenge, was given short shrift in the intelligence preparation effort. Ironically, there was tremendous consideration given toward minimizing civilian casualties and collateral damage to critical Iraqi infrastructure needed for follow-on stabilization efforts. However, such analysis and consideration was done largely under the umbrella of “intelligence preparation for combat operations.”

Moreover, that incomplete analysis failed to recognize the historical truth that it is the people and the infrastructure that have borne the brunt of post-combat resistance.

There remained a gap in campaign planning for the period between cessation of major combat operations and wholesale stabilization of the country, a gap that had strategic implications. That historical pitfall is at the root of the following passage from Joint Publication 5-00.1, Joint Doctrine for Campaign Planning.

“Not only must intelligence analysts and planners develop an understanding of the adversary's capabilities and vulnerabilities, they must take into account the way that friendly forces and actions appear from the adversary's viewpoint. Otherwise planners may fall into the trap of ascribing to the adversary particular attitudes, values, and reactions that “mirror image” US actions in the same situation, or by assuming that the adversary will respond or act in a particular manner.“ (25)

Unfortunately, much as the French viewed the Spaniards two centuries earlier, U.S. planners were left to peer almost exclusively through a western lens in the hope-filled analysis of the probable response of various segments of this 25 million person country toward coalition stabilization and support efforts. Succinctly, little professional analysis was conducted in order to answer the tough questions, “What is it about their society that's so remarkably different in their values, in the way they think, compared to my values and the way I think in my western, white-man mentality?” (26)

That intelligence gap left far too much to wishful thinking and was the context for several broad assumptions that proved to be invalid. Whereas planners left no stone unturned in the intelligence preparation of the battlespace as it related to the defeat of Iraqi forces and ultimate removal of the Hussein regime, there was little corresponding depth to the analysis of the next necessary target audience within the campaign design, the Iraqi people. Policymakers, commanders, and planners alike were content to lean on the frail assumption that the coalition would be accepted by Iraqis throughout the country with open arms.

Chapter 4: Bridging the gap

“We must be cognizant of the changing roles and missions facing the Armed Forced of the United States and ensure that intelligence planning keeps pace with the full range of military operations.” (27) – GEN Hugh Shelton, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff

The U.S. military must accept the fact that the post-hostilities environment is central to campaign design if the political objectives are to be achieved. Properly estimating the magnitude of stability and support operations that will be necessary after the end of decisive combat operations is the only way to prevent the emergence of a strategic gap. It is the military that will have to grapple with the immediate and diverse challenges that accompany the cessation of large-scale combat operations. To the central point, it is the military that immediately will have to deal with the indigenous population until the cavalry arrives in the form of more support-focused and better resourced U.S. agencies and organizations, international aid organizations, and reconstruction specialists.

General Zinni described just such a chaotic environment during an address to the Armed Forces Staff College fully a decade ago:

“The situations you're going to be faced with go far beyond what you're trained for in a very narrow military sense. They become cultural issues; issues of traumatized population's welfare, food, shelter; issues of government; issues of cultural, ethnic, religious problems; historical issues; economic issues that you have to deal with, that aren't part of the METT-T process, necessarily. And the rigid military thinking can get you in trouble. What you need to know isn't what our intel apparatus is geared to collect for you, and to analyze, and to present to you.” (28)

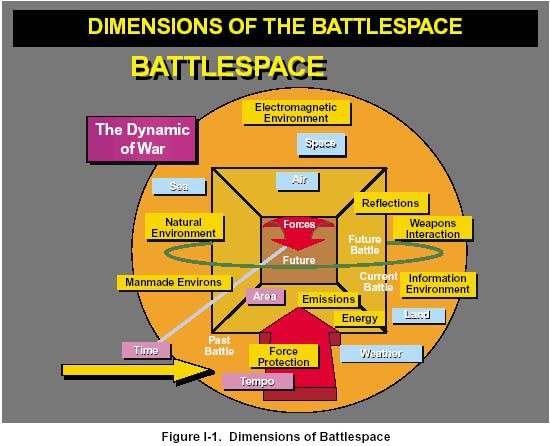

While current Joint intelligence doctrine that is specially focused on the “people” is not completely barren, the anaemic level of detail that is dedicated to intelligence requirements focused on a people's history and culture is a direct reflection of the imbalance of the current IPB process. As a picture is worth a thousand words, the glaring omission in the figure below, taken from the lead joint doctrinal publication for intelligence, perhaps sums up best the current mindset of the joint community regarding where “the people” fit within the intelligence requirements for the development of a coherent campaign design.

If properly balanced, a corresponding red arrow entitled “people” would be in the center of this diagram opposite the existing red arrow entitled “Forces”. This would draw attention to the reality that the civilian population will be the centrepiece of the post-hostilities environment. As currently depicted, this view of the battlespace does little to reinforce the requirements within Joint Publication 5-00.1, Joint Doctrine for Campaign Planning which states that “campaign planners must plan for conflict termination from the outset of the planning process and update these plans as the campaign evolves” and “emphasizing backward planning, decision makers should not take the first step toward hostilities or war without considering the last step.” (30)

Furthermore, Joint Publication 3-0, Doctrine for Joint Operations states, “US forces must be dominant in the final stages of an armed conflict by achieving the leverage sufficient to impose a lasting solution.” (31) Such a leverage toward a lasting solution (grand strategic endstate) can only be achieved if the requisite historical and cultural understanding has been incorporated into the overall planning effort.

Currently, joint doctrine for intelligence does not lay the foundation for achieving such leverage. Just as a scan of joint publications suggests that “military professionals embrace the idea of a termination strategy, but doctrine offers little practical help,” (32) a review of doctrine for intelligence preparation of the battlespace reveals only short, topical passages on “The Human Dimension,” “The Populace”, and the “Effects of the Human Dimension on Military Operations,” and only after the various elements of the battlespace contained in the figure have been elaborated upon.

Chapter 5: Striking a balance

Our intelligence system is designed to support a Cold War kind of operation. We are “Order of Battle” oriented. We are there to IPB the battlefield. (33) – Gen. Anthony Zinni

The US armed forces must change with that world [a terribly changed and rapidly changing world] and must change in ways that are fundamental – a new human understanding of our environment would be of far more use than any number of brilliant machines. We have fallen in love with the wrong revolution. (34) – Ralph Peters, 1999

With such references to “backward campaign planning” and “achieving leverage,” why then do we maintain such an imbalance in our intelligence preparation of the battlespace in the crafting of a holistic campaign design? Or to paraphrase General Zinni, “Why are we only planning for a three inning ballgame?” One part of the answer may be that,

“Western military forces are not political forces, and professional war fighters like the US and British military tend to see peace making and nation building as a diversion from their main mission. It also seems fair to argue that conflict termination and the role of force in ensuring stable peace time outcomes has always been a weakness in modern military thinking. Tactics and strategy, and military victory, have always had priority over grand strategy and winning the peace.” (35)

Compounding this problem, the “gravitational pull” of ever-improving technology coupled with the drive toward “Transformation” have resulted in the adoption of a mindset that more can be done with less to achieve the decisive effects in recent and future campaigns. In certain aspects of campaign planning, increased efficiency and effectiveness resulting from technological breakthroughs lend credence to this line of thinking. However, policymakers, commanders and planners alike must be ever mindful that efficiency should not be held up as the overarching goal at the expense of better understanding. (36)

Unfortunately, intelligence preparation of the battle space, the driver of campaign planning, has been co-opted by the same fascination with efficiency. With a heavier focus on the employment of technologically more advanced collection systems, the delta between collection efforts focused on enemy forces and those intelligence efforts focused on the people, “The last six innings of the ballgame”, if you will, has actually widened. As Ralph Peters wrote in Fighting for the Future, “We need to struggle against our American tendency to focus on hardware and bean counting to attack the more difficult and subtle problems posed by human behaviour and regional history.” (37)

In the dozen years between Operations DESERT STORM and IRAQI FREEDOM, the U.S. military made tremendous technological strides in its efforts to increase all aspects of its joint warfighting capability, specifically the overall lethality of the force, joint information management, and situational awareness driven by enhanced collection capabilities. But it is clear that the joint force did not place the same premium on gaining an adequate understanding of the Iraqi people and their culture. In analyzing the current situation in Iraq, an astute citizen wrote in a letter to the New York Times, “There is a crucial need for cultural anthropologists in Iraq even more than capable Arabic speakers. Linguistic knowledge is one thing, but understanding the conventions, subtleties and nuances of a language and culture is something different.” (38)

There immediate steps should be taken to bridge future cultural intelligence gaps.

The first step must be the acceptance that history is important and while it may not repeat itself as some might argue, it surely holds the clues that will shed light on current and future cultural intelligence requirements. Robert Steele, in his monograph The New Craft of Intelligence, reinforces the importance of historical analysis stating, “The first quadrant [requirement], the most fundamental, the most neglected, is that of the lessons of history. When entire volumes are written on anticipating ethnic conflict and history is not mentioned at all, America has indeed become ignorant.” (39) Such ignorance would never be tolerated by commanders at any level in preparations for combat operations. That same intolerance must be maintained in planning for missions across the operational spectrum within a comprehensive campaign design.

Yet, solving the “puzzle of the people” cannot be the sole domain of military intelligence officials, the small group of foreign or regional area officers, or even the extremely competent but clearly undermanned and over-tasked Special Forces, civil affairs, and translator units and detachments sprinkled throughout a large-scale campaign's area of operations. Rather, just as the U.S. defense establishment has increased overall efficiency and effectiveness by looking to all corners of the civilian business world within the military hardware acquisition process, so too must the joint force expand its horizons in the development of new intelligence doctrine. Since doctrine is a guide, the force must be guided in its intelligence activities by those who can provide the strongest beacon on historical and cultural issues. In looking “toward motivational and value similarities, the military should be looking for a few good anthropologists” (40) as well as historians, economists, criminologists, and a host of other experts who can provide the depth of understanding that will lay the foundation for success in post-hostilities.

The second step should be a culturally-oriented addition to the intelligence series within joint doctrine. The scant references to post-conflict intelligence focused on an indigenous population that are currently imbedded within several joint publications, namely JP 2-01.3 Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace and JP 3-07 Joint Doctrine for military Operations Other Than War, do not adequately address the myriad of unconventional intelligence challenges that are inevitable in the chaos of modern post-hostilities environments. Peters, a career Army intelligence officer, admonishes us:

“Military intelligence is perhaps more a prisoner of inherited Cold War structures than is any other branch…Our intelligence networks need to regain a tactile human sense and to exploit information technologies without becoming enslaved by them. In most of our recent deployments, no one weapon system, no matter how expensive and technologically nature, has been as valuable as a single culturally competent foreign area officer.” (41)

An addition to the intelligence series could take a page or two from the Marine Corps Small Wars Manual. In its simplicity, the Manual discussed at length the psychology of a country's population. Specifically, it states, “human reactions cannot be reduced to an exact science, but there are certain principles that should guide our conduct”. (42)

Furthermore, “These principles are deduced only by studying the history of the people” and “a study of the racial and social characteristics of the people is made to determine whether to approach them directly or indirectly or indirectly, or employ both means simultaneously”. (43)

Finally, the Manual warns that “psychological errors may be committed which antagonize the population of a country occupied and all the foreign sympathizers; mistakes may have the most far-reaching effect and it may require a long period to re-establish confidence, respect, and order”. (44)

The third step builds on the previous two and bridges the cultural gap through holistic backward planning that achieves intelligence leverage. William Flavin argues for just such a paradigm shift in intelligence preparation of the battle space in his Planning for Conflict Termination and Post-Conflict Success:

“The IPB should address political, economic, linguistic, religious, demographic, ethnic, psychological, and legal factors…The intelligence operation needs to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions that must exist for the conflict to terminate and the post-conflict effort to succeed.” (45)

The U.S. Joint Forces Command, tasked with the lead for Transformation within the Department of Defense, has taken a first step in placing more emphasis on cultural intelligence and the imperative to understand a country's or region's dynamics well beyond fielded forces or other potential combatants. The Draft Stability Operation Joint Operating Concept focuses on the vital period within a campaign that follows large-scale combat operations. As importantly, this concept stresses the requirement for different focus of intelligence:

“Situational understanding requires thorough familiarity with all of the dynamics at work within the joint area of operations: political, economic, social, cultural, religious. The joint stability force commander must have an understanding of who will oppose stabilization efforts and what motivates them to do so.” (46)

In reinforcing the fact that the joint force will remain the lead agent for an unspecified period of time upon cessation of hostilities, this concept further highlights the imperative for detailed planning and involvement for a post-hostilities phase across all of the warfighting specialties, specifically intelligence, from the outset of campaign planning. Furthermore, by articulating the critical nature of the period within a campaign when “the joint stability force begins imposing stability throughout the countryside to shape favourable conditions in the security environment so that civilian-led activities can begin quickly”, (47) this concept links theatre means to grand strategic political endstates. It levies the requirement that intelligence analysis reach depths rarely explored within our current conventional intelligence mindset. Specifically that, “On-going human intelligence efforts identify potential cultural, religious, ethnic racial, political, or economic attitudes that could jeopardize the post-hostility stability operation. The intelligence capabilities begin to focus on the unconventional threat posed by total spoilers. Human intelligence also focuses on the identity, motivation, and intentions of limited and greedy spoilers.” (48)

These different categories of spoilers will not be uncovered by conventional intelligence preparation and will remain undetected by our most technologically advanced collection assets. Spoilers will “swim in the sea of the people” and will require a sophisticated and precise intelligence mindset to separate them from the masses and ultimately extinguish the threat they pose to the achievement of the strategic endstate. Such sophistication recognizes that the intelligence focus of the battle space in post-hostilities must shift from the physical to the domain, with the paramount concern being the “minds” of those who might oppose stability. (49)

Chapter 6: Conclusion and future implications

What will win the global war on terrorism will be people that can cross the cultural divide. Its an idea often overlooked by people [who] want to build a new firebase or a new national training center for tanks. (50) – GEN. John Abizaid, Commanders, U.S. Central Command

Proper intelligence preparation of the battle space focused on the people and the unique challenges of a post-combat operational environment will continue to challenge the Joint Force in the 21st Century just as it proved to be Napoleon's Achilles Heel two centuries ago. If we are to apply Napoleon's maxim that “The moral is to the physical as three to one” within a truly holistic campaign design, then perhaps such a ratio should be applied in balancing the collective intelligence effort, with a focus on the people assuming paramount importance. That will require addressing intelligence challenges that are unconventional and uncomfortable for planners and commanders at all levels. Comprehensive backward planning with a balanced intelligence effort throughout the width and depth of the envisioned campaign will ensure that “forces and assets arrive at the right times and places to support the campaign and that sufficient resources will be available when needed in the later stages of the campaign”. (51)

Just as it proved to be the beginning of the end for Napoleon's dominant influence in Europe, giving the importance of “the people” short shrift within the strategic calculus may be the prescription for failure within future military campaigns. Technology is not a panacea within our joint warfighting construct, and especially across the spectrum of intelligence requirements.

As the world becomes even more complex, it is critical to understand the root causes and effects of the histories and cultures of the peoples with whom the joint force will interact. Relying less on high-tech hardware, such a mental shift may be the most transformational step the military can take in preparing for the challenges of the 21st Century. These requirements cannot be met with a narrowly focused approach toward intelligence preparation of the battle space. As Ralph Peters stated at the end of the 20th Century,

“We will face a dangerous temptation to seek purely technological responses to behavioural challenges – especially given the expense of standing forces. Our cultural strong suit is the ability to balance and integrate the technological with the human, and we must continue to stress getting the balance right.” (52)

Sophisticated cultural intelligence preparation of the battle space may not pinpoint exactly where opposition flashpoints may occur within a post-combat operational environment. However, by achieving appropriate IPB balance, beginning with a bolstered joint intelligence doctrine, the joint force will reduce the potential for strategic gaps by helping to prepare for the “Sunni Triangles” or “Navarrese Diamonds” of the future.

If the current modus operandi of insurgents in Iraq is an indicator of the total disregard that future adversaries will have toward global societal norms, the joint force will, in many respects, be operating with one hand tied behind its back. The U.S. military can ill-afford to have the other hand bound through the development of comprehensive campaign plans not grounded in solid cultural understanding of countries and regions within which it will likely operate. To do so risks adding yet another footnote to history, highlighting an intelligence gap between combat and stability and support operations.

Bibliography

Books

– Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1966.

– Esdaile, Charles. The Peninsular War: A New History. New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2003.

– Gates, David. The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986.

– Lovett, Gabriel H. Napoleon and the Birth of the Modern Spain. 2 Vol. New York: New York University Press, 1965.

– Peters, Ralph. Fighting For The Future: Will America Triumph? Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 1999.

– Strange, Joe. Capital “W” War: A Case For Strategic Principles of War. Quantico, VA: U.S. Marine Corps University, 1998.

– Tone, John Lawrence. The Fatal Knot. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

– Van Creveld, Martin. The Transformation of War. New York: The Free Press, 1991.

– Von Clausewitz, Carl. On War, translated and edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Periodicals

– Basham, Patrick and Radwan Masmoudi. “Is president Bush Pushing for Democracy too Quickly in Post-Saddam Iraq?” Insight on the News, 19, no. 26 (Dec 2003): 46.

– Boule II, John R. “Operational Planning and Conflict Termination.” Joint Force Quarterly, Issue 29 (Autumn 2001 – Winter 2002): 97-102.

– Malkin, Lawrence. “The First Spanish Civil War.” Military History Quarterly (Winter 1989): 19-27.

– O'Connell, Kevin, Robert R. Tomes. “Keeping the Information Edge”, Policy Review, (Dec 2003/Jan 2004), 19.

– Schaffer, Ronald. “The 1940 Small Wars Manual and the “Lessons of History.” Military Affairs, 36 (Apr 1972), 46-51.

– Tyson, Anne Scott. “A General of Nuance and Candor; Abizaid Brings New Tenor to Mideast post.” Christian Science Monitor (March5, 2004), 1.

– Zinni, Anthony. “Understanding What Victory Is.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings 129, no. 10 (Oct 2003): 32-33.

– “G.I's in Iraq: A Cultural Gap.” New York Times [Letter], Oct 27, 2003, A.20.

Internet Resources

– Cordesman, Anthony H. “The Lessons of the Iraq War: Issues Relating to Grand Strategy.” Available from http://www.csis.org/features/iraqlessons_grandstrategy.pdf.

– Flavin, William. “Planning for Conflict Termination and Post-Conflict Success.” Available from http://carlisle-www.army.mil/usawc/Parameters/03autumn/flavin.pdf.

– Steele, Robert D. “The New Craft of Intelligence: Achieving Asymmetric Advantage in the – Face of Nontraditional Threats.” Available from http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/pubs/2002/craft/craft.pdf.

Official Documents

– National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: The White House, September, 2002.

– U.S. Joint Forces Command. “DRAFT Stability Operations Joint Operating Concept.” Available from http://www.dtic.mil/jointvision/draftstab_joc.doc.

– U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Doctrine for Intelligence Support to Joint Operations, Joint Publication 2-0. Washington, D.C.: The Joint Staff, 9, March 2000.

– U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Joint Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace, Joint Publication 2-01. 3. Washington D.C.: The Joint Staff, 24 May 2000.

– U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Doctrine for Joint Operations, Joint Publication 3-0 Washington D.C.: The Joint Staff, 10 September 2001.

– U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint Doctrine for Campaign Planning, Joint Publication 5-00.1 Washington D.C.: The Joint Staff, 25 January 2002.

– U.S.Marine Corps. Small Wars Manual. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1940.