French cuisine has been renowned in Europe and beyond for centuries, indeed so much so that having ones own personal French chef was once considered to be the height of sophistication. And the Revolution and consequent flight of wealthy families from France, gave the sovereigns and princes of old Europe access to French culinary masters via the entourage of French émigrés. But once the Directory took over, French gastronomy returned to France, to reach its apogee during the Consulate and Empire. Revolutionary frugality gave way to fine dining and fine drinking as the risk of famine disappeared. Gastronomy became a sort of cult, with haute-cuisine periodicals, not to mention guides and manuals, springing up like mushrooms, such as the Almanach des gourmands (1803), the Journal des gourmands et des belles (1806) and Grimod de La Reynière’s Manuel des amphitryons (1808), Cadet de Gassicourt’s Cours gastronomique and Cussy’s Art culinaire. Gastronomical ‘clubs’ were founded, such as that founded by Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, a magistrate at the Cour de Cassation. Brillat-Savarain was later to write in his book, Physiologie du Goût ou Méditations de gastronomie transcendante par un professeur: “The destiny of nations hangs on the way they eat” (1825).

This style of cooking and the gastronomical lifestyle won over not only the French elite, but also the notables and even middling types of lesser means, as restaurants began to emerge. This new type of eatery allowed customers to match their menus to their appetite and desires, as opposed to having to put up with the single dish fare of the Auberges. In Paris, crowds flocked to restaurants such as Le Vefour, La Marmite perpétuelle, Le Bœuf à la mode, Le Veau qui tête, Le Rocher de Cancale (specialising in seafood), etc. Soon, the whole of France followed suit, with famous restaurants springing up elsewhere, such as for example, La tête de bœuf in Abbeville, L’hôtel de la cloche in Dijon, L’hôtel d’Angleterre in Toulouse, etc.

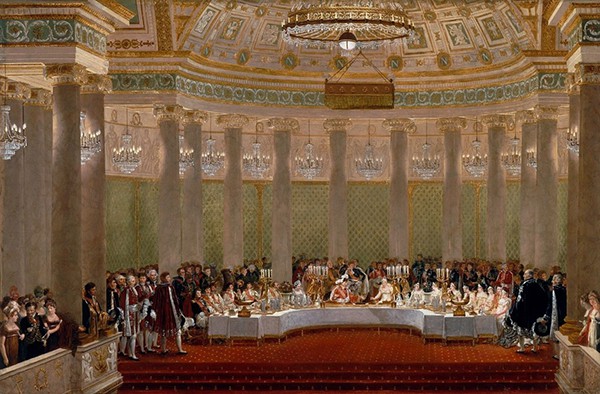

In the houses of the great and the good, a kitchen team was de rigueur. There was even a sort of ‘mercato’, with fierce competition for the best savoury or pastry chefs, the most famous of whom being Marie-Antoine Carême, a sort of free-lance cook who had to be booked months in advance. He was often employed by Cambacérès, Talleyrand and even Napoleon himself for grand dinners.

Whilst it is true that Napoleon was not at the forefront of this conquest, he was nevertheless not immune to its attractions. It was important for him that his table be sumptuous and well served. His guarantee in this respect was, on the one hand, Dunant, the imaginative chef previously employed by the Prince de Condé, famous above all for his improvised recipe, ‘Chicken Marengo’, and, on the other, Farcy, an excellent cook and poultry wizard. That being said, apart from the grand court dinners, these maestros were not often asked to stretch their talents to the limit, and they were probably disappointed to note how their master rushed through his meals, regardless of the care with which they had been prepared. Napoleon never spent more than a quarter of an hour at table, at least as far as lunch was concerned. He had a special weakness for chicken, and it could be cooked any which way (with saffron, stuffed, in a tomato sauce, with truffles, …). He also loved macaroni, roast lamb, grilled lamb breast, boiled or stewed meat, lentils, haricot beans (fresh and dried) and, for pudding, a pastry, dried fruit, or a waffle. He washed it all down with a glass of Chambertin wine diluted with ice-cold water. Occasionally, he would have a cup of coffee or tea to cap what could scarcely be called a feast.

Napoleon generally ate this midday meal either alone (his entourage remaining standing in the salon) or with certain dignitaries. It is said that the latter took the precaution of eating beforehand, knowing full well that they would not have time to finish what was on their plate (Napoleon would give the signal for the start and the end of the meal). Dinner, however, could stretch out longer and be eaten with family members: the Empress dined with him every day; Madame Mère and the brothers and sisters when present in Paris would come on Sundays.