Pretty much everyone can name the main local administrative institutions set up in France by Napoleon, for the most part during the Consulate: Prefects, Sub-Prefects, Mayors, Conseils Généraux, etc. And much sport has been made in the context of this list, noting how the institutions on it were a way of affirming government authority, giving rise to a sort of “authoritarianism”. It has been less noted that the erection of this pyramid of responsibilities and competences had a decisive effect in achieving the national unity of France.

To put it this way, Napoleon wanted to streamline and reinforce the executive in its actions, and to do this he decided to make the administration “the backbone of the state”, thereby marking himself out from those who had gone before him. He modernised the administration and made it strictly pyramidal. It is true that the Ancien Régime had wanted to create such a structure, as had the Revolution, but thanks to the powers granted to him via the Brumaire coup d’État and then the Constitution of An VIII, Bonaparte managed it in a few months.

Strongly linked to Bonaparte’s general character and his will to accept all the potential consequences, the specific nature of the solution comprised namely: the rejection of the election of administrators, the professionalisation of the body of civil servants, and the creation of a fixed administrative hierarchy. This centralisation was to be applied to everyone, everywhere, regardless of the place or nature of the activity. Following the Revolutionary doctrine of the unity and indivisibility of the Republic, local particularities were considered of less importance. By doing this, Napoleon created what could be called the “administrative constitution” of contemporary France. In the face of the great upheavals in the political constitution, the centralised administration made it possible for the state to be stabilised, whilst at the same time contributing to the prosperity of the country.

The law prescribing the constituent parts of the administration was promulgated on 28 Pluviôse An VIII (17 February 1800). And it was to remain on the statute books, despite certain amendments, some quite significant, until 1982, and its eminent economy was never challenged. Large parts of the law still survive, including notably the administrative parcelling and prefectural institution.

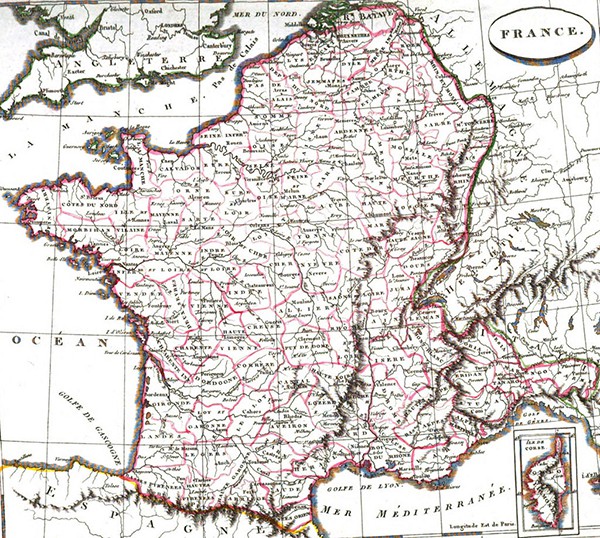

The country was divided up into Départements, Arrondissements and Communes. Each of these constituent parts was organised around an executive and a deliberating assembly: a Prefect and Conseil Général for the Département, a Sub-Prefect and Conseil d’Arrondissement for the Arrondissement, and a Mayor and Conseil Municipal for the Commune. Prefects, Sub-Prefects, and Mayors and Deputy Mayors of Communes with more than 5,000 inhabitants were appointed by the head of state. The Mayors of communes with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants were chosen by the Prefect. All these executives were arranged in a strict hierarchy, the prefect directing the daily duties of Sub-Prefects and Mayors. This general scheme was the practical application of one of Sieyès’s best-known maxims: “Deliberation is a matter for the many, execution is a matter for a single person”.

The Département was the defining constituent part, and its administration was redefined with respect to the preceding period. Attempts were also made, empiric ones, it must be said, to go beyond the departmental frame, whilst at the same time preserving it as the base unit. Administrative circumscriptions were created which oversaw several Départements, almost “regions” before the letter, for the Gendarmerie and the Army, not to mention certain fiscal administrations. But the logic of this was not forced such that the same Départements should remain part of same group of Départements, nor that these “regional” administrations should be accommodated in the same towns. There is however one remarkable exception, namely: the creation of Governors General to oversee the Prefects of recently annexed Départements.

The French Empire comprised one hundred and thirty-four Départements in 1812 (forty-five of which were actually outside “old” France, sometime described as Départements “étrangers” or Foreign Departments), as opposed to eighty-three in 1790, ninety-eight in 1799 and one hundred and eight in 1804. The Prefect was “alone in charge of the administration”.

The Arrondissement was a new constituent part. There were 329 in 1801, and 527 in 1813. The officers for these circumscriptions were few in number and of lesser importance, the Sub-Prefects’ roles being limited to the oversight of the running of the communes and the correct collecting of taxes.

The communes were given back their own administrative officers; they had been taken away by the Directory. There were 45,768 communes on French territory in 1801, and probably nearly 60,000 within the 1812 boundaries, despite the strong political will of the Napoleonic regime to combine them. The role of the Mayor was re-established over this fundamental constituent part of the country. He was “alone in charge of the administration” of the commune, his missions including public order, management of communal goods, births, deaths and marriages, streets, preparation of the budget, and ordonnancing of expenses, etc. That being said, this low-level administrator had little room for manœuvre; expenses had to be covered by income from communal goods, by the centimes added to national taxes, a miserly contribution of higher authorities, and, on occasions, in only a few thousand localities, octrois or local taxes.

Prefects, Sub-Prefects and Mayors, executive officers, were assisted in their work by non-elected councillors: a Conseil Général, a Conseil d’Arrondissement and a Conseil Municipal, respectively. And so as to avoid the problem of the noisy and uproarious “general assemblies” of yesteryear, councillors were carefully selected, and their roles were largely consultative. Sessions were short, convoked by the Prefect once a year and lasting fifteen days at the most. “Councillors” were given dossiers that were deliberately restricted in scope; any desires they may have had concerned most often local interests, and when they did look further afield, their remarks usually comprised of flattering addresses to the Emperor.

Through this structure, Napoleon aimed above all at administrative efficacy (and it was a huge success). However, his decisions had other consequences, ones that were not entirely unexpected. It would be wrong to simplify these actions by saying that Napoleon simply superimposed a “military model” on his administration. He also aimed to render irreversible the principle of the unity and indivisibility of the Republic, and later the Empire, a direct inheritance of Revolutionary doctrine. Unity was to be pursued in several directions at once, namely: constitutional, jurisdictional (with the creation of a single Tribunal de Cassation for the whole of the territory), and administrative (with the uniform parcelling up of the country). Napoleon hated nothing more than a fragmentary state and social dissolution. These decisions were never challenged, and his principles of political and administrative unity must have contributed significantly to the reinforcement of national unity.