Is it true that Napoleon wanted to be a writer?

With Napoleon in mind, Adolphe Thiers wrote with enthusiasm: “The age had an immortal writer, immortal as Caesar; namely the sovereign himself, a great writer because he had a great mind”.Historical Works, Volume 3 By Adolphe Thiers. I can’t argue with that: Napoleon could have become a writer, if events had not favoured his military and then political career.

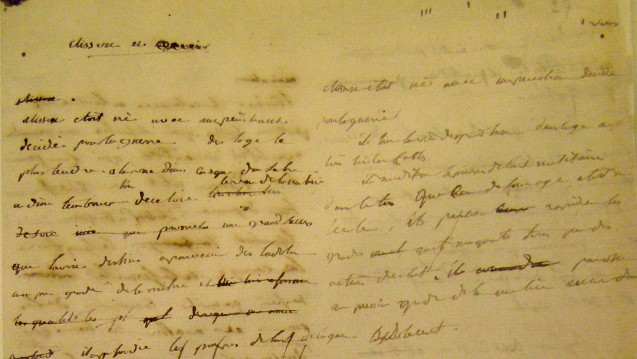

In his youth, Napoleon enthusiastically tried his hand at practically all the literary genres, writing numerous texts, many of which have survived, although he later tried to throw away the most personal ones: there were novels, including Le comte d’Essex [The Earl of Essex](1789), Le Masque Prophète [The Mask of the Prophet](1789), [La Nouvelle Corse] [The Corsican Novel] (1789), and Clisson et Eugénie (1795), philosophical essays, such as Le Parallèle entre l’Amour de la Patrie et l’Amour de la Gloire [The Parallel between the Love of Country and the Love of Glory], (1786), le Discours de Lyon [The Discourse for the Lyons Academy] (1791) and le Dialogue sur l’Amour [Dialogue on Love] (1791), purely political writings such as Les Corses ont-ils eu le droit de secouer le joug des Génois [Did the Corsicans have the right to shake off the Genoese yoke?] (1786), the Constitution de la Calotte du Régiment de la Fère [The Calotte for the de la Fère Regiment](1789), the Lettre à Matteo Buttafoco [Letter to Matteo Buttafoco] (1791) or the famous Souper de Beaucaire [Supper in Beaucaire], his first published work (1793). These early compositions, sometimes only sketched out, belong to the literary history of the 18th century, which sometimes makes them difficult for us to appreciate today, conditioned as we are by the Romantics and their literary successors. Some of his texts are nevertheless of high quality.

The next “chapter” in Napoleon’s career as a writer produced prose of a different calibre – in the pursuit of quite different goals. Stylistically too there is a change: there is greater precision, and suddenly sharp formulas – almost like maxims – abound. These are the writings not just of a legislator, a ruler, a leader and a propagandist, but also of a truly literary political author. Napoleon never stopped writing (in his illegible hand) or dictating (to secretaries who had trouble keeping up with him). His entire written production must represent tens of thousands of pages: correspondence, orders, proclamations, notes, legal texts and even newspaper articles that he inserted in the pages of the official newspapers in his service, such as the Moniteur Universel. On St Helena, he dictated (and then corrected) many notes not only on the art of war but also on books written about him. He even began writing his memoirs, but only succeeded in completing three volumes: the Italian Campaign of 1796-1797, the Egyptian Campaign and the Hundred Days.