Between 1803 and 1805, and with the aim of effecting a “descent” upon England, Napoleon established a multitude of encampments on the Channel and North Sea coastlines, from Utrecht to Montreuil, known globally as the “Boulogne camp” because that was where the Emperor had his headquarters. By June 1805, there were more than 150,000 men, 10,000 to 15,000 horses and 500 artillery pieces in the different camps. To transport these troops and their materiel to the other side of the Manche, a thousand flat-bottomed boats and 750 barges (variously called ‘prams’) were built. All that was needed was some clear weather during which the ocean-going navy could block the straits for forty-eight hours so that this “armée des Côtes de l’Océan” [Ocean Coast Army] could invade the British Isles in order to “go and seek peace in London”. The French navy never managed to keep to its part of the plan since it was blockaded within different European ports by the Royal Navy. And it was in trying to force its way out of the Cadiz stranglehold that the largest of these fleets was sent to the bottom at Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. In the meantime, however, the Emperor and his army had already left Boulogne and were hundreds of kilometres away. After beating the Austrians at Ulm, occupying Vienna, and destroying at Austerlitz (2 December 1805) the coalition that had formed against him, Napoleon was in the end forced to abandon the invasion project.

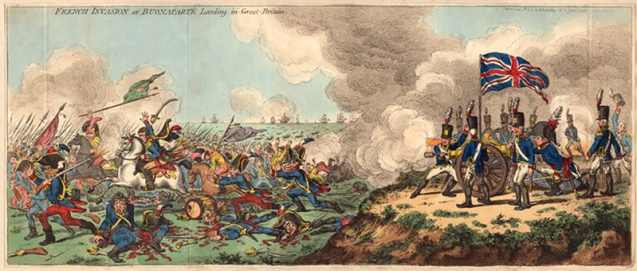

People have occasionally wondered whether he was really serious here. Some have thought that the Boulogne Camp was merely a demonstration of force designed to push Britain to the negotiating table, or that it was a diversion aimed at persuading Austria that the Emperor had no intention of “hurling” himself into the centre of the continent. Furthermore, in this scenario, the concentration of his forces is said to have cleverly allowed Napoleon to neutralise the different political forces within the army leaving only one, one that was favourable to the imperial regime. These hypotheses are destroyed by the sequence of events (in 1803, nobody could have guessed that war with Austria and Russia would flare up again), by the enormous resources deployed in the creation of the immense invasion flotilla, by the huge sums sequestered from barely stable national finances in the modernisation of the fleet and the equipping of the troops, and, above all, by the passion – almost exaltation – with which Napoleon and his staff prepared the invasion. In Britain, the threat was taken extremely seriously with the levying of troops and the construction of a chain of defence towers along the coast (many still survive), and the general public were mobilised both as whistle blowers (the French are coming!) and in militias supposed to repel the invaders. Only because he was constrained and forced by maritime failures and threats from central Europe did Napoleon abandon his great project. From now on, victory over perfidious Albion would have to come via continental victories.