Dartmoor Prison: the French connection

It was seven years ago that Alain Sibiril, Plymouth's Honorary Consul of France, first became aware, via Trevor James, the local writer who used to work at the prison, of the memorial to the French prisoners who died at Dartmoor while being held captive during the later years of the Napoleonic Wars.

Over eleven hundred French nationals lost their lives while being held under conditions that today we would consider inhuman; a further 218 American soldiers and sailors died under the same conditions and at the same time. For many years the graves of these men who were laid to rest without funeral rites, lay unhonoured in a field adjacent to the prison. In her review of the area published in 1845 Miss Rachel Evans noted that horses and cattle had broken up the soil, leaving the bones of the dead to whiten in the sun.

The prison had lain more or less empty after the war had ended and it was not until 1850 that it was brought back into service. Within a few years the then Governor of the Prison, Captain Walter Stopford, unearthed thousands of skeletal remains and ordered inmates to gather the remains into two mass graves, one designated French, the other American. He then had an obelisk for each erected as a memorial with the legend 'Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori'.

Prison life

Having been alerted to the state of the memorial in more recent years M. Sibiril suggested that perhaps the crew of a modern French warship might restore the memorial; however that work has now been carried out by the current generation of prisoners and tomorrow there will be a special service in the church of St Michael and All Angels, at Princetown (at 11am), to commemorate the bicentenary of the arrival of the first French prisoners of war at the prison. It was 24 May, 1809 that some 2,500 Frenchmen were marched from the overcrowded prison hulks in the Hamoaze, and from Millbay Prison, to the small village on Dartmoor that the enterprising Thomas Tyrwhitt was looking to develop, along with other large tracts of the moor. St Michael and All Angels was largely constructed by French prison labour and is not always open these days, so it will be a welcome opportunity for some to see inside this unusual Dartmoor building.

Having been alerted to the state of the memorial in more recent years M. Sibiril suggested that perhaps the crew of a modern French warship might restore the memorial; however that work has now been carried out by the current generation of prisoners and tomorrow there will be a special service in the church of St Michael and All Angels, at Princetown (at 11am), to commemorate the bicentenary of the arrival of the first French prisoners of war at the prison. It was 24 May, 1809 that some 2,500 Frenchmen were marched from the overcrowded prison hulks in the Hamoaze, and from Millbay Prison, to the small village on Dartmoor that the enterprising Thomas Tyrwhitt was looking to develop, along with other large tracts of the moor. St Michael and All Angels was largely constructed by French prison labour and is not always open these days, so it will be a welcome opportunity for some to see inside this unusual Dartmoor building.

It is heartening to reflect that the Napoleonic Wars, which ended in 1815, were the last occasion that the British and the French were foes on the battlefield, and tomorrow the French Ambassador from London, M. Gourgault-Montagne, will be present at the service; so too will be representatives from three families that are directly descended from three of the prisoners that were incarcerated here, and another from the family of a French officer held here on parole, who met and fell in love with a beautiful country girl (despite the best efforts of the authorities to prevent such liaisons).

While there can be no doubt that the fortress prison was very much a 'great tomb for the living' (as described by Sir George McGrath, the medical officer there from 1814-16) it is worth remembering how poor conditions were generally at that time – it was claimed that the official returns showed that the mortality among prisoners was less, in proportion, than in any town in England, with equal population. Among servicemen generally the statistics were even more horrific; of the 90,000 or so British sailors who were lost during the Napoleonic Wars, less than 7,000 were killed in action, the rest mainly succumbed to disease, shipwreck or accident. Furthermore, many of the men held in Dartmoor brought the ‘seeds of infection' with them, and the conditions were not conducive to a return to health. Sanitation was poor and it is estimated that up to 9,000 men were here at one time during that period.

The men gambled, duelled and fought for food and clothing. Hundreds, who styled themselves Romans, wore nothing but a single-holed blanket (to put their heads through) outdoors and went naked in their billet indoors. Curiously, despite swapping their main provisions for tobacco, these men's bodies hardened to the conditions and their survival rate appears to have been better than the rest. But many were not so fortunate. Gambling meagre provisions on the length of straws pulled from a mattress or the number of turns a sentry might perform in given length of time, or the number of curls on the doctor's wig, the men would risk all and many paid the ultimate price.

French prisoners memorial obelisk

In 1865, fifty years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and fifteen years after Dartmoor had once again been pressed into the prison service, Captain Walter Stopford, the then Governor of the infamous, isolated bleak pile of buildings on the moor, collected the partially exposed remains of French and American prisoners who had died there and had two memorial erected on the site. Each bore the legend 'Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori' – 'it is sweet and right to die for one's country'. Quoted by Lord Lovat before he was beheaded on Tower Hill in 1747 and subsequently used ironically by Wilfred Owen in his famous First World War poem, the line first appeared over 2,000 years ago in one of the Roman poet, Horace's, Odes. Some 1,129 French prisoners died between 1809 and 1815 at Dartmoor Prison, and soon after Stopford's gesture an acknowledgement was received that showed the act of international courtesy was appreciated in France.

In 1865, fifty years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and fifteen years after Dartmoor had once again been pressed into the prison service, Captain Walter Stopford, the then Governor of the infamous, isolated bleak pile of buildings on the moor, collected the partially exposed remains of French and American prisoners who had died there and had two memorial erected on the site. Each bore the legend 'Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori' – 'it is sweet and right to die for one's country'. Quoted by Lord Lovat before he was beheaded on Tower Hill in 1747 and subsequently used ironically by Wilfred Owen in his famous First World War poem, the line first appeared over 2,000 years ago in one of the Roman poet, Horace's, Odes. Some 1,129 French prisoners died between 1809 and 1815 at Dartmoor Prison, and soon after Stopford's gesture an acknowledgement was received that showed the act of international courtesy was appreciated in France.

In recent years, the memorial has been restored.

Images

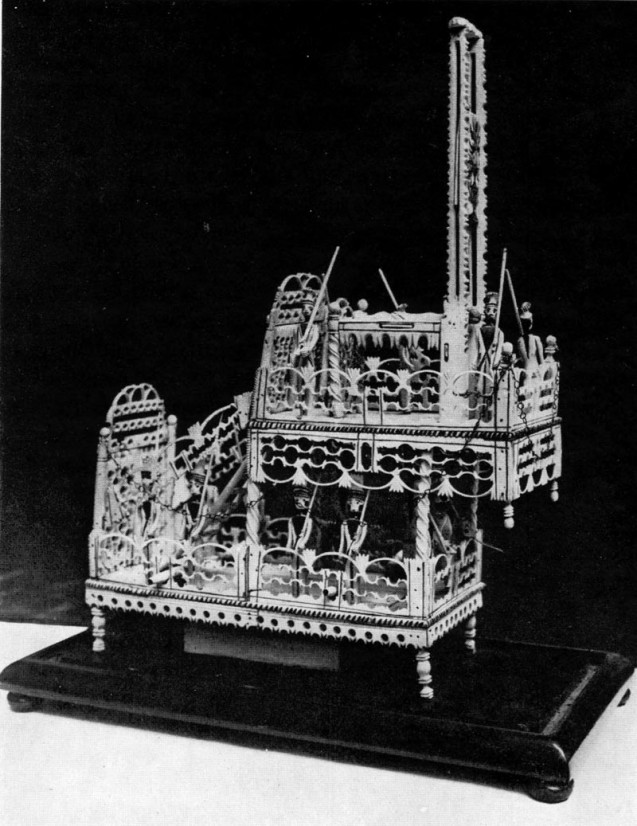

1. & 1A. Models of a guillotine and warship constructed and carved from beef bones by French prisoners at Dartmoor, 1809-1815 (and both currently on display in Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery).

1. & 1A. Models of a guillotine and warship constructed and carved from beef bones by French prisoners at Dartmoor, 1809-1815 (and both currently on display in Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery).

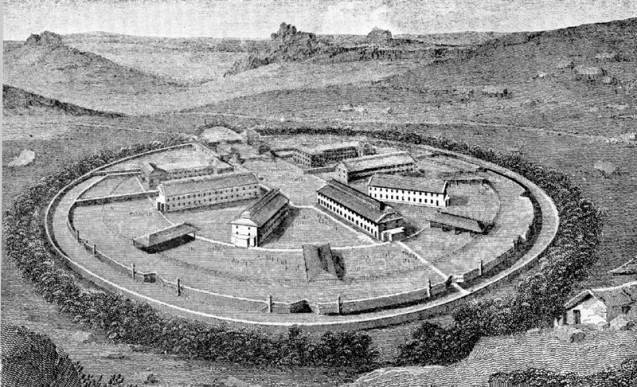

2. A perspective view of the original buildings (two of which were built by the French prisoners).

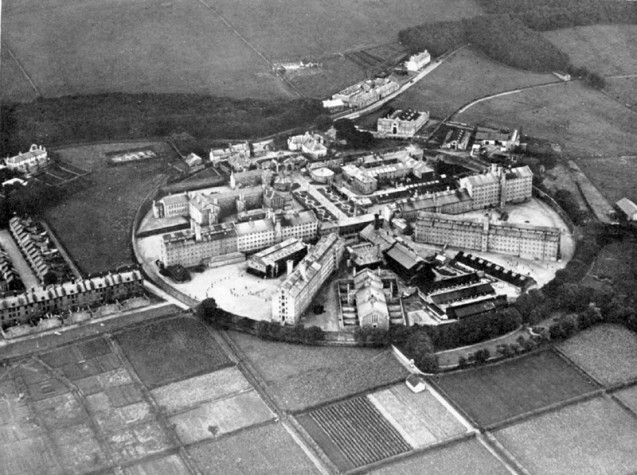

3. An aerial view from the early twentieth century.