[See original document online]

This was not the first time that leading characters of the Revolution had declared that the Revolution was over.

Since 1789, the end of the Revolution had often been promised as part of various propaganda efforts. One example was when, in August 1789, leading monarchists declared that the Revolutionary chapter was closed and that all of the necessary political and social reforms had been completed. In the following year, characters as diverse as Mirabeau and Lafayette were making the same claims, shortly to be repeated by the influential ‘left-leaning’ figures (known at the time as the Triumvirate), namely, Lameth, Barnave and Duport. Even Saint-Just, later a leading figure during the Reign of Terror, was to speak of the Revolution as a thing of the past in the introduction to his 1791 manuscript, Esprit de la Révolution et de la Constitution de FranceIn this work, Saint-Just attempted to find out ‘the causes, the consequences and the ending’of the Revolution (Théorie politique, 1976, p.38).. One last example (although there are lots of others to be found) was when, during the discussion concerning the adoption of the Constitution of the Year III [1795], the député, Baudin des Ardennes, took to the speaker’s platform and announced to the Convention that, this time, they really had brought the Revolution to an end.

How did Bonaparte and his allies want to ‘finish’ the Revolution?

Until 1799, no one had been able to figure out how to ‘finish’ the Revolution. They could stop it. They could try to channel it and take it in a calmer and more controlled direction, or they could bring it to a full stop on the basis of the principles most accepted by the different organs of government and political players. Those behind the coup of 18 Brumaire chose the third solution, and this is expressed in their proclamation. They wanted to govern from the centre-leftJ.-J. Chevallier; Histoires des Institutions et des régimes politiques de la France de 1789 à nos jours, 1977, p.106., distancing themselves from political Jacobinism, but also positioning themselves far from the vengeful Counter-Revolution. They were intent on upholding the major principles of 1789 and wanted to enact the ideas in the speech made by Bonaparte at the founding of the Conseil d’Etat: ‘We have finished the passionate and philosophical ‘roman’ [novel] of the Revolution; we must now begin its history, only seeking for what is real and practicable in the application of its principles, and not what is speculative and hypothetical. To follow a different path today would make us philosophers and not governors.’

What did the word ‘fini’ actually mean in 1799?

It is crucial to consider words in the context of the time in which they were spoken when studying historical texts, or else the intended meaning is lost.

The Consuls announced that the Revolution was ‘finie’ [finished]. According to the 1799 edition of the Dictionary of the Académie Française, ‘fini’ had two specific meanings:

• The first, ‘parfait’, translates as ‘perfect’, with the same meaning as today’s expression, ‘produit-fini’, meaning ‘finished product’.

• The second, ‘terminé’, translates as ‘ended’.

By using the word, ‘fini’, the Consuls wanted their contemporaries to understand both of these definitions. For them, the Revolution was a ‘finished product’ (according to the principles established in 1789) and ‘ended’.

Which principles did the Consuls decide to keep?

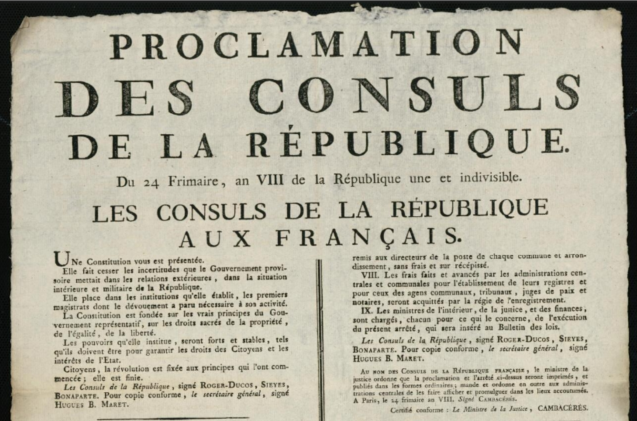

The principles the Consuls decided to keep are included in their proclamation:

A constitution lies before you. It puts an end to the uncertainties that the provisional government caused for our foreign relations and for the domestic and military situation of the Republic. It creates the institutions and appoints the primary magistrates whose zeal is required for the function of those institutions. The Constitution is founded on the true principles of representative government, on the sacred rights of property, equality, and liberty. The powers it establishes are strong and stable, as they must be to guarantee the rights of the citizens and the interests of the state. Citizens, the revolution is established on the principles that began it. It is finished.‘Aux français,’ 24 Frimaire Year VIII, 15 December 1799, Correspondance de Napoléon Ier; document no. 4422.

The text shows that they proclaimed to have finished (or to have made complete) the political revolution, the essential aim of which had been to ensure the emergence of a representative regime and with that equality and liberty. They reinforced this by declaring the social right of property as sacred, before going on to specify that these rights could only be guaranteed by a ‘strong and stable’ government.

Was Bonaparte’s Consulate part of the Revolution?

Most history textbooks divide the French Revolution into four periods (the National Constituent Assembly, the National Legislative Assembly, the National Convention, and the Directorate). Bonaparte’s Consulate is generally excluded.

However, two historians in particular reject this almost official compartmentalisation, disagreeing with it on a number of levels. The volume dedicated to the Directorate and the Consulate periods in the French popular ‘knowledge’ handbook series Que sais-je?, entitled Le Directoire et le ConsulatCollection ‘Que sais-je?,’ no. 1266. First Edition (Souboul), 1967, edited by Albert Soboul in 1967, and again by Jean Tulard in 1991, paved the way for a new perspective. They believed that if we have to divide the Revolution into periods for practical reasons, we ought not to set these periods in stone, or consider them ‘sacred’. For Soboul and Tulard, despite what was taught in universities, we could no longer question the fact that there was continuity between the Directorate and the Consulate, and more broadly, between the first ten years of the Revolution and the regime founded by the Constitution of the Year VIII [1799].

Cart before the horse?

Earlier history writers detached the Consulate from the ‘Revolution’, interpreting the period according to what happened subsequently and not following the chronology, allowing Napoleon’s later history to colour that previous. However, when studying the Consulate, it is much more interesting to think about it as if we don’t know what came after. If we do this, then the Consulate looks much more like a continuation of the Directorate, rather than the regime that preceded the Empire. If we study the ‘present’ of the Consulate, we see that it makes much more sense when seen in the context of its past.

Author: Thierry Lentz, Historian, Director of the Fondation Napoléon, April 2019 (translation PH and JR)

Notes:

(1) In this work, Saint-Just attempted to find out ‘the causes, the consequences and the ending’ of the Revolution (Théorie politique, 1976, p.38).

(2) J.-J. Chevallier; Histoires des Institutions et des régimes politiques de la France de 1789 à nos jours, 1977, p.106.

(3) ‘Aux français,’ 24 Frimaire Year VIII, 15 December 1799, Correspondance de Napoléon Ier; document no. 4422.

(4) Collection ‘Que sais-je?,’ no. 1266. First Edition (Souboul), 1967