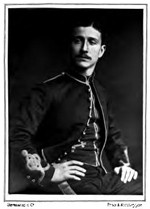

“Chapter XIX: Death”, from Life of the Prince Imperial. With Portrait, by Ellen Barlee (London: Griffith and Farran, 1880)

DEATH

“What recks it where the casket lies

When the gem it shrined hath gone?

Who bids the funeral pile arise

When the deathless soul has flown?

And yet may honours duly paid,

Truth's tears, appease a warrior's shade –

For a martyr's death atone.

Fallen chief: this offering half divine,

The incense of the heart, is thine.”

I have now brought this narrative up to the date of the fatal day, which, in the annals of the Zulu war, will ever bear the black mark of a national disaster. The sad event, which there struck down the hope of a great nation, had annexed to it the humiliating fact that the Prince was left alone and unsupported in his death-struggle, his own party deserting him on the first alarm of Zulu proximity, without one attempt to rally for his rescue. The circumstances of the catastrophe were at first surrounded by such contradictory statements, that the truth seemed difficult to unravel, but they appear to have been as follows: —

On the 25th May the head-quarters were established at Landsman's Drift, and the Prince, ever eager for work, applied for employment, when he was directed to prepare a plan of a divisional camp. That evening Lord Chelmsford spoke to Colonel Harrison as to the Prince having gone outside the lines without a proper escort. Colonel Harrison replied that the work the Prince had engaged in referred to the camp inside the outpost lines. The General then gave a fresh order, that the Prince was not to engage in work which took him at a distance from the camp, unless he had a strong escort. Colonel Harrison then said he would report the General's orders to the Prince.

That same day Colonel Harrison saw the Prince, and told him of the General's orders, and, to make sure, gave him his instructions in writing. Colonel Harrison also asked the Prince to make a map of the country from a reconnaissance sketch of Lieutenant Carey's, which the Prince executed well.

On the 28th May the head-quarters were moved to Koppie Allein; and during the next three days reconnaissances were pushed into the enemy's country, but no Zulus were seen. Early on the 1st of June, Lord Chelmsford, before leaving the camp at Koppie Allein, missing the Prince from his post at his side, inquired, “What has become of him?” The reply was that he had gone on slightly in advance of the column with Colonel Harrison. The duties of Colonel Harrison that day, in connexion with General Newdegate's, were the supervision of the transport of troops, &c.; and, knowing there that the former officers could not be far ahead, the Commander-in-Chief was satisfied as to the Prince's safety, and said no more on the subject.

It appeared that the Prince had heard that morning early that another reconnaissance was contemplated; and having been debarred from joining the last, owing to his duties in camp, he begged to be set free from desk-work and volunteered to conduct the party. Colonel Harrison, seeing that the Prince was bent on doing this, yielded to his solicitations, and an expedition was planned, which, had it kept to its original limits, involved no risk, inasmuch as the column was about to follow in the track, and the Prince's objective was to go ahead and find a suitable place for their encampment. While the scheme was under discussion, Lieutenant Carey happened to come in and asked leave to accompany the Prince, but said that he was rather inclined to extend the ride, as he wished to finish some sketches of a part of the country near the valley of Ityolyozi, which two days before he had left uncompleted. On hearing this, the Prince, who was ever ready to be in advance, especially if such an advance led on the road to adventure, willingly assented to push the reconnaissance in the direction of Ityolyozi, a distance of eleven miles beyond the boundary of the first proposed reconnaissance. Colonel Harrison's faith in Lieutenant Carey's knowledge of the country was so great that he doubted not that the Prince would be safe under his surveillance. The question was thus settled.

The Prince was to be nominally the commander of the sortie, and Lieutenant Carey virtually its guide, and the Prince's adviser and abettor; but had the latter not been of the party, the prolonged reconnaissance would never have been sanctioned.

The only further question that remained to be decided was what escort should accompany them. According to military rule, it was the Cavalry Brigade Major's duty to detail the escort, unless special orders were given otherwise. This generally, for a small sortie of the kind, consisted of six men of Bettingham's Horse, and six men of Shepstone s Mounted Basutos.

When Lieutenant Carey, however, applied to the Brigade Major, he offered him either the usual escort, or to hand him a service order, and let him secure his own troops from the respective commanding officers themselves. Lieutenant Carey selected the latter course; and, as time was an object, he obtained six white men from Bettingham's corps, and sent one of them to Shepstone's force for the Basutos.

Meantime, the Prince and Lieutenant Carey, as soon as their messenger returned, rode leisurely along with their six troopers and a black Kaffir guide, who had been enlisted in their service, leaving word that the Basutos were to follow at once, and join them on the mountain ridge near Itelizi.

On arriving here the party waited for an hour, expecting the Basutos every minute to come up.

The views from this ridge are very picturesque, the ground undulating all around, and the hills expanding into mountain ranges which stand out in bold relief, and in grandeur of form and colouring. Sharp descents into the various valleys below, lead to depths of wondrous beauty, only to rise again on the other side into an extensive panorama of hill and dale.

When the hour had passed, and no Basutos appeared, the Prince's impetuosity could brook no further delay, and he expressed his determination to proceed without them. Lieutenant Carey at first showed reluctance; but, in excusing himself later for yielding, said he considered that the Prince was the captain of the party, and did not like to oppose his wishes, especially as, two days before, he had been reconnoitring in that direction, and had seen no Zulus. He should, however, have borne in mind that he had then a large force of Dragoons with him, whose presence would have scared away any of the enemy lurking about.

On the ridge the party met Colonel Harrison, who does not seem to have used any remonstrances, either to induce them to return, or to wait for the Basutos.

These latter, it appears, were not even en route to join them, for the message left with them was not sufficiently definite, as to what course they were to take, and the Brigade Major could not enlighten them, hence they did not follow at all. After another hour and a half's riding, the Prince's cavalcade, reduced to nine persons, viz., himself, Lieutenant Carey, six troopers, and the Kaffir guide, arrived upon the heights above the valley of Ityolyozi, the precise spot where Lieutenant Carey's sketches were to be corrected, and which exhibited the same features of soft undulating beauty as the previous heights where they had rested en route.

Here the Prince also produced his note-book, and used his pencil freely. Their drawings finished, the Prince led the way down into the valley below, following the windings of the river, until he arrived at a kraal at the foot of the hill. This kraal had evidently only lately been vacated, for, on entering the huts, which were five in number, there was a strong smell of smoke, and two or three dogs were running about.

These warnings, with the adage that “Prudence is the better part of valour,” were disregarded, and, with inconceivable rashness, the Prince, after peering into the huts, gave the order to “off saddle,” whilst no one seems to have gainsayed him, or remonstrated at the want of due precaution such a step involved.

The kraal was surrounded on three sides by high tambookie grass, and standing crops of corn and mealies, the front being left open for a width of twenty yards or so. Here the party then lay down while their attendants prepared coffee, and the horses were turned into the grass for a meal also.

At 3.45pm, after a good hour's rest, Lieutenant Carey suggested it was time to return. The Prince, who was engaged in sketching, decided to remain, however, ten minutes longer; but; in a few minutes, put away his pencil and gave the order to saddle the horses.

When the Kaffir who fetched the horses returned, he said “he had just seen a Zulu on the hill opposite.” At that moment the Prince, who was standing at his horse's head, gave the final order.

“Prepare to mount. Mount!”

The words were hardly out of his mouth, and before the order could be carried out, a volley rang through the clear air, and resounded among the adjoining hills, and a cry of “The Zulus” was heard; while at the same moment the heads of the blacks were seen emerging from the long grass a few yards off, they having crept thus far within range of fire unobserved.

Coming on with a wild cry, the Zulus fired again, and hit a trooper, who fell dead under their volley, another trooper, Letocq, falling soon after.

At the first sight of the Zulus, without waiting to discover whether their numbers were many or few, there was a general “Sauve qui peut,” and the small party which had accompanied the Prince, putting spurs to their horses, galloped off as fast as they could, not drawing rein till they had distanced the enemy; nor do they appear for some time to have even looked back, in order to see if all their numbers were in safety.

At the moment when the volley was fired the Prince was in the act of putting his foot into the stirrup; but his horse, startled at the noise, bolted, before he, agile horseman though he was, could succeed in mounting him. With his usual agility, however, he ran after his horse, and succeeded in catching hold at last of the pommel of the saddle. Alas! the leather gave way, and it tore off in his grasp.

At that moment, poor youth, he must have realized his danger indeed, for far, far ahead of him were his companions, in rapid flight; whilst a few yards behind, in full hue, with their hideous, savage cries, and with their assegais brandished in the air, were his enemies, who were gaining fast upon him. He continued running, however, until he reached the donga, some considerable distance from the kraal, and here, into the midst of its deep, damp ground, the Prince plunged, and there seems to have stood at bay and faced his enemies, first emptying his revolver, which was found near, unloaded, and afterwards, in closer combat, with his sword.

No British eye witnessed this mortal fight to record its full details; an after-examination of the ground proved, however, that the Prince must have made a desperate struggle for his life, for the few accoutrements which were found near the spot told this tale, testifying how his blood had flowed. No need to dwell on this dark side of the picture. In the heat of action blood may flow even unheeded, and without suffering; and the calm, placid expression of his face, when found, betokened anything but agony.

We love rather to hope, then, that valour conquered fear, and that, in the excitement of the struggle, he met with an instantaneous and painless death.

The evidence of one of the troopers at the court martial, held afterwards, was that, “as soon as he had himself arrived at the donga, he looked back, and saw the Prince running a few yards in advance of about nine Zulus, who were about five yards behind him. Seeing this, he levelled his carbine, with the intent to fire on the enemy; but at that moment his horse plunged into the donga and threw him forward on his neck. He says that when he recovered his position, the Prince's horse was just in the act of passing him, and he caught its bridle and took it with him into camp, as at that moment Lieutenant Carey called out to the party to make for Wood's Camp.”

He also stated that, as soon as he had crossed the donga he once more looked back, and saw the Prince still running ahead of the Zulus by three or four yards, and that he called out to tell his companions so; but no orders were given to rally. The Zulus were, he says, armed with guns and assegais.

Meantime, as soon as the retreating party reached the camp they reported their attack by the enemy, and when asked anxiously by those at head-quarters “what had become of the Prince,” replied that no doubt he had been killed; that in fact it was a certainty, as he could not have escaped — news which carried dismay and grief into every heart.

Then indeed came the too tardy recognition of the unwise course adopted, in having allowed him, or indeed any of the force, to proceed so far without a proper escort.

It was then suggested by one of the Prince's personal attendants, and seconded warmly by M. Deléage, the Paris newspaper correspondent, that no time should be lost in sending out a strong body of troops, to recover the body if possible; as, they added, the Prince might possibly be lying wounded only, and anxiously looking for help. This idea did not find immediate response; night was fast falling over the hill, and the authorities, convinced that it was impossible that the Prince could have escaped from the hands of the Zulus with his life, determined to defer the search for his body until the next morning. His attendants expostulated, but could not alter their decision. At seven a.m., on June 2nd, a regiment of cavalry, under the command of General Marshall, with a large corps of volunteers, Lieutenant Carey, and the two troopers who had accompanied the Prince the day before, with the Prince's servant Lomas, set forth on their sad errand, all on horseback.

On arriving at the valley of Ityolyozi, and reaching the kraal where the party had rested the previous day, an old Zulu woman came out of one of the huts shouting that it had been inhabited by the enemy during the night.

The grass behind the kraal was so high that the horses were almost hidden in it as they advanced.

As the searching party neared the donga, one of the horses in advance, just after he had descended the sides of the donga, suddenly stopped on his own accord, and his rider discovered, in the bushes, the corpse of one of the troopers who had been shot in the attack? The body had been horribly mutilated; its stalwart size told at a glance, however, that it was not the Prince's.

Two hundred yards further off, at most, a cry was raised that a second corpse was lying in the donga; and on riding up, it was at once recognized as that of the Prince. He was lying on his back, his arms crossed over his chest, and the head slightly inclined to the right. The Zulus had stripped the body, but had spared it most of the horrible humiliations usually inflicted by them on their enemies.

The Prince's countenance showed no trace of suffering, but retained its usual sweet expression; one eye was wide open, and lifted heavenwards; the other had been pierced by an assegai. On examining the body no less than seventeen assegai wounds were discovered, but all in front; not a wound was found behind — showing how nobly the brave young Prince had faced his foes.

Truly, no one could affirm the fear, his child's voice had expressed when operated upon in 1866, “that he had run away from his enemies.”

The principal wounds were in his arms; and here again their number proved how long he must have defended himself with his sword, before his enemies could strike at any vital point.

Around his neck was a locket, also a small fancy seal he always wore attached to it, which the Emperor Napoleon I. had brought from Egypt.

The news that the Prince's body had been found, soon brought the entire scouting party to the spot! Their numbers had been augmented by Colonel Buller with another body of volunteers, all eager to render such aid as they could in the search.

Curious indeed was the scene witnessed that morning on those far off heights in that distant land. Picture it for a moment, my readers, if you can!

A range of hills, over which the early morning light is breaking, with soft, mingled hues of primrose, pale green, and rosy tints, which, in the distance, deepen into darker shades of purple and amethyst. The slopes into the valley are covered with horsemen in scarlet uniform, who ride hither and thither with earnest glances and bated breath. ON a sudden there is a shout! was it triumph or dismay? All rally in one direction, and the banks of the donga are soon alive with soldiers and horse. These quickly gather around – what – the extended corpse of a youth, the near descendent of that man whose warlike deeds, when first narrated to the young Zulu chief, Chaka, first aroused his martial ardour to emulate the conquests of Napoleon I.

Alas! it is the heir of that Napoleon's dynasty who now lies in their midst, slain by the savage fury of a portion of the Zulu tribe whom white men first instructed in the finer arts of war, and over whom grey-haired veterans and hardy soldiers shed scalding tears. Some of their number indeed bend low over the body, and reverently kiss the Prince's pale and placid face. The corpse was easily recognized before even his friends drew near it. The slight, lithe form could belong to none other. Carefully the body was wrapped in blankets and placed on a bier formed of lances, the highest officers in rank who were present acting as bearers; thus it was slowly carried up the heights, and along the route to where an ambulance had been ordered to be in attendance, about a mile in advance. To this it was carefully transferred. The Lancers, Dragoons, and Volunteer forces followed it as escort.

The journey to the camp occupied three full hours; once there, the body was deposited in one of the tents.

That same afternoon a funeral parade was held outside the camp, attended by all the troops. The bier, covered with a tricoloured flag, was put on a gun-carriage, and slowly conveyed down the line of troops until it arrived at a spot where the 17th Lancers were formed. In front of that corps, the funeral service was then read by the Rev. G. Belfort, Roman Catholic Chaplain to the Forces, the Protestant clergyman also being present.

The Princes remains were at night put into a shell, hastily formed from some tin-lined packing boxes, the only available materials at hand.

The next day orders arrived that the body should be sent to the capital.

When the Prince's remains left the camp, a detachment of Lancers accompanied it as far as

Koppei Allein, and from thence an escort of Carbineers to Landsman's Drift. Here it remained for the night, after which it had to traverse the Buffalo River. The next stage was Dundee, where, after a halt of some hours, the funeral train proceeded to Ladysmith. Here the inhabitants assembled round the coffin, and, bringing out the church harmonium, sand hymns and dirges, and every fresh halting-place en route the same interest and religious ceremonials awaited it.

The Governor went out two miles in advance of the road by which the Prince's remains were brought into the town, accompanied by a procession, formed by all the civil and military authorities of the capital in full dress uniform. He had previously caused a cannon to be sent forward, on which the coffin was placed, and thus it was escorted into the town. Here, certain forms of identification had to be gone through; these were signed by the Governor, Uhlman his body servant, and M. Deléage, the French correspondent. One of these documents was placed in the coffin, one was sent by the French Consul to Paris, and one was placed in the archives of the colony.

The body was also re-embalmed at Maritzburg. Within the Prince's coffin was placed the little crucifix found on his neck, which had been a present from the Pope, with a photograph of the Empress, bearing the signature “Eugénie, le 27 Fevr. 1879,” the day his mother had last parted from him.

When the poor Prince left the capital for the camp, he had desired his trusty servant, Uhlman, to remain at Maritzburg. The grief of this man, when he heard of his master's death, was almost beyond control, and he blamed himself bitterly for not having disobeyed him, and followed him into the camp. Uhlman had lived in the Imperial family ever since the Prince's birth, never having left him before for a single day, and his grief may well be imagined.

The following order was issued to the troops in Natal in reference to the embarkation of the remains of the Prince Imperial : —

“Soldiers,

“The mortal remains of Prince Louis Napoleon will be transported to-morrow at half-past nine a.m. to the Roman Catholic Church at Durban, Port Natal, to be afterwards embarked on Her Majesty's ship the 'Boadicea' for England.

“In following the coffin which contains the corpse of the Prince Imperial of France, and in rendering to his ashes the last tribute of respect and honour, the troops in garrison will remember : —

“1. That he was the inheritor of a powerful name and one of great military renown.

“2. That he was the son of England's strongest Ally in times of danger.

“3. That he was the only child of a widowed Empress, who now remains without a Throne, in Exile and childless, on the shores of England.

“To enhance the sorrow and respect which they owe to his memory, the troops will bear in mind that the Prince Imperial of France fell in fighting under the English flag.

“W.P. Buller, A.-A.-General.”

The next day a solemn funeral service was held at Maritzburg, after which the sad procession started en route for Cape Town. At Durban the same tokens of respect awaited the cortège. The inhabitants of this town escorted the remains to the port. Every house in the town en route to the latter place, closed their shutters, and hoisted the French flag half-mast high from their windows. The “Boadicea” transferred the coffin to the “Orontes,” passing with its burthen between a line of men-of-war boats, the crews of which stood with their oars peaked, and their heads uncovered.

At Cape Town, Sir Bartle and Lady Frere, with all the military and civil authorities, went to Simmon's Bay and on board the “Orontes.” Here once more a solemn service was perofmed by the Roman Catholic Bishop of Cape Town. Lady Frere and other friends brought wreaths and flowers, wherewith they surrounded the coffin. The voyage to England occupied twenty-one days, Captain Pemberton being in charge of the Prince's remains. The passage was a fair one, and on the 10th of July the “Orontes” anchored at Spithead. She was commanded by Captain Kinahan. At Spithead the “Enchantress,” an Admiralty yacht, commanded by Captain Hills, met the “Orontes,” and the coffin was transferred to the former vessel without delay, still, however, being in charge of Captain Pemberton. Several of the Empress's friends, however, joined the “Enchantress” at Spithead. On Friday, the 10th, the “Enchantress” lay-to at the pier of the Woolwich Arsenal. Here a distinguished company of both French and English persons, with the Prince of Wales and his Royal brothers at their head, awaited the vessel.

The Prince Imperial's coffin was borne on shore by the sailors of the Admiralty yacht, M. Rouher, General Fleurry, and other deeply-attached friends of the deceased, walking on either side of it.

Poor M. Rouher, who was terribly overcome when he first heard of the Prince's death, had exclaimed, with tears in his eyes, “I have nothing now left to live for.”

On arriving at the Arsenal, the coffin was put into a temporary mortuary, draped for the occasion in black, and here further forms of identification had to be gone through. That evening the Prince's remains were put upon a gun-carriage, over which the tricolour flag of France and our British flag were thrown, and were transported to Camden House, Chislehurst.

When the sad news of the Prince's death had first arrived in England, the Queen had begged that great care might be used in making it known to the Empress, and Lord Sydney proceeded at once to Camden House to break it to her. Those about the Empress had tried to keep her in ignorance of the event until Lord Sydney's arrival by detaining her newspapers and letters; but unfortunately she opened a letter addressed to her secretary, M. Piétri, who was absent, and there learned, not indeed the full extent of her misfortune, but that something very sad had happened to her son.

Ever since the day of his departure, the Empress had, with a mother's touching love and anxiety, caused preparations to be made which would enable her to start at once for Africa should she hear he was ill. On opening M. Piétri's letter she therefore at once rang, and ordered her servants to prepare for her immediate voyage to Natal. Then it became necessary to inform her “it was too late.” Her grief can be better imagined than described. All was not, however, told her at first, and it was only in fact by degrees, little by little, she learned the full tale of sorrow and disaster which had rendered her future a blank.

To attempt to analyze her grief would be both out of place and impossible. In the drama of life, as well as on its theatrical stage, at the supreme moment of some tragic scene the curtain falls, and the company can only through imagination picture what takes place behind its heavy folds. In the bereavement of the Empress, and over her hours of agony which followed, we likewise drop the curtain.

“She sat alone, and heard the nations cry, —

‘Lo now the child is dead!'

But his memory shall not fade,

Nor the halo die

That shineth around his head;

For his shall be the glory, and his the power,

And his the kingdom be;

And he shall reign — not for a little hour,

But — everlastingly.”

H. Charles.

Excerpt from "Life of the Prince Imperial"

Author(s) : BARLEE Ellen