“Evening issue: Read all about it!”

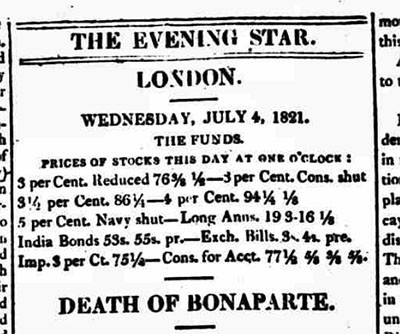

On 4 July 1821, the front page of the London newspaper The Star was full of daily life in London. Mr Flowers of No 1 Pall Mall “at the end of the Royal Arcade” had taken out a quarter column to advertise his “wines of fine quality only”. Another quarter column was occupied by a “MAGNIFICENT LOTTERY” where you could win £25,000 (the equivalent of 457 years pay for a daily labourer, the wage in 1821 being 3 shillings (= 36 pence per day)). Small adverts included essays on practical husbandry, second-hand pianos and a pedal harp, a book of views of Paris and Sicily. A very canny salesman latched onto the upcoming coronation of George IV to recommend his Macassar Hair oil, “the finest auxiliary of beauty being a fine head of hair”! On the back page, however, printed clearly in a second edition for the day (since it reported events of the morning under the title “Evening Star”) and probably the second page readers would come to, in full caps, stood the extraordinary news “DEATH OF BONAPARTE”.At least three newspapers, The Statesman, The Globe and The Star, were to reset their back pages for their second, “evening” edition to announce the hot-off-the-press news that the Emperor was no more. Whilst the Star and Globe named Hendry as the bearer, the Statesman repeated Hendry’s news, but added Crokat’s report as ‘further particulars’.

Heron and the first news

Earlier that day, captain William Hendry “of the sloop of war, Rosario” had arrived from St Helena bringing news, so the report ran. Hendry had viewed Napoleon’s corpse on 6 May and had been detailed by Admiral Lambert to leave his vessel Rosario (of which he was nominal captain) and to board Heron to deliver the news to the Admiralty. Despite the fact that the newspapers announced the arrival of Heron in Portsmouth on 5 July, the ships must clearly have arrived early on the 4th and allowed Hendry to disembark beforehand to give him the time to reach London by midday on that day. The article noted how Hendry had come from the Portsmouth in “a chaise and four”, an expensive and speedy vehicle, arriving at the Admiralty at 11.30am. The despatches were sent immediately to the King. The Star’s scoop, stated “from the best authority” was “the death of the Ex-Emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, [an] event, which in every generous and Christian sense of the term, we may call melancholy” that took place on 5th May, of stomach cancer, like his father. The article gave his age correctly, but following the British biographical tradition on Napoleon, that had begun as early as 1797, claimed that Napoleon had “post-dated his birth two or three months, for some political reason or other, which we at present forget.” The article went on to note the constant activity of the Admiralty telegraph and supposed that news must have reached France, “where it cannot fail to produce an extraordinary sensation”. That being said, as we know from recent research, the reaction in Paris was muted. The only real error in this breaking news was the claim that the Emperor had died in New Longwood House. Though the article mentioned that news from Hudson Lowe had likewise been communicated to East India House nothing was said of Captain Crokat. Did he disembark later than Hendry? Was there a competition between the two, Navy versus Army? The Saint James’s Chronicle dated Thursday 5 July 1821 noted that Hendrie [sic] arrived before Crokat and his news to Lord Melville at the Admiralty was taken by Wilson Croker to the King, whilst Crokat’s news, arriving apparently slightly later, was taken to Bathurst and the East India Company.

The Governor’s report

The official report from the governor was to emerge in the papers the following day, 5 July. Whilst, as noted, The Star’s article dated 4 July had referred to a letter from Hudson Lowe to be delivered to East India House and read in the General Court of Directors there, London readers now learned that Captain Crokat of the 20th regiment, Hudson Lowe’s official messenger also travelling on Heron, had brought with him the official despatches for Lord Bathurst of the Ministry for War and the Colonies and the East India Company. Since Lord Bathurst was not in his office and Crokat’s orders were to deliver the news into the hand of the minister, Captain Crokat went on to Bathurst’s house in Stanhope Street. Bathurst then was said to have sent the news to the King and ordered that a round robin be sent to parliament.

Rosario, news of Napoleon’s funeral on St Helena, and the first “pictures” of the dead Emperor

Since Crokat and Hendry had left the island on board Heron on 7 May, their news did not include an account of Napoleon’s funeral that took place two days later. For that London readers had to wait a few days for the publication of a private letter brought in Rosario under Captain Frederick Marryat which had left St Helena on 16 May (one version of this letter given below was printed on 9 July, though other versions of it appeared slightly earlier). Marryat (like Hendry and Crokat) had viewed Napoleon’s corpse on 6 May. Rosario had managed to make good time, eating five or six days out of the 8-day advantage that Heron had in its departure. The “Ship News” in the Morning Post for Monday 9 July 1821 recorded that this vessel had arrived in Portsmouth on 6 July merely two days after Heron (Marryat noted in his diary for 6 July “anchored at Spithead”), though it had left St Helena more than a week later.

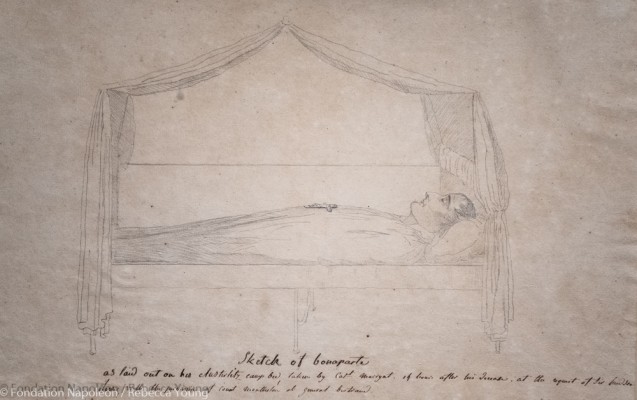

In addition to official papers (Marryat was bringing duplicates of the initial despatches brought by Crokat and presumably Hendry) Rosario also brought with it the first (private) details concerning Napoleon’s funeral on 9 May. The vessel was also however bearing the French commissioner Montchenu’s official report of Napoleon’s death. Montchenu had missed Heron’s departure on 7 May because he was asleep… Crokat and Hendry however had brought with them “A likeness of Buonaparte, after his disease, […] sketched by an English officer”. As The Statesman (a London publication) dated Saturday 7 July noted: “[Marryat] made several copies, some of which have been brought to England by the officers who arrived on Wednesday [i.e., Hendry and Crokat on 4 July]. The article was of course referring to Marryat’s famous sketch of Napoleon’s corpse on the death bed; Marryat himself would arrive on Rosario the following day. The Saturday issue of The Sun alleged that Hudson Lowe had requested the sketch and that Montholon and Bertrand had given their permission. Other sketches by Marryat were also referenced notably “of his tomb, which is placed in a very romantic situation, and of the Funeral Procession from Longwood.” The Sun also claimed that Napoleon’s will had been brought back in Rosario.

Many of the first accounts of Napoleon’s death on 4th and 5th July noted how the British treasury would now be freed from paying £400,000 per annum in upkeep for Napoleon at Longwood.

On 8 July The British Luminary published Lowe’s dispatch to Lord Bathurst in full and also a version of the autopsy report.

Napoleon’s Lying in State

On Sunday 8 July 1821; The News (a London newspaper) published a private letter dated 7 May that described Napoleon’s lying in state as follows:

“An immense number of persons, both yesterday and this morning, have been to see him. It was one of the most striking spectacles at which I have ever the fortune to be present. The view of his countenance, from which I felt it scarcely possible, even for an instant, to withdraw my eyes, gave me a sensation I cannot describe; his hands were white as wax, and felt soft, though the chill of death was upon them. His remains must soon be closed from mortal view. In this warm climate dead bodies soon become offensive, and though all the dispatch possible is used in preparing the leaden coffin, it is already time that he was soldered up. General orders are issued that he is to be buried with the highest military honours; and perhaps Thursday or Friday next will be the day.”

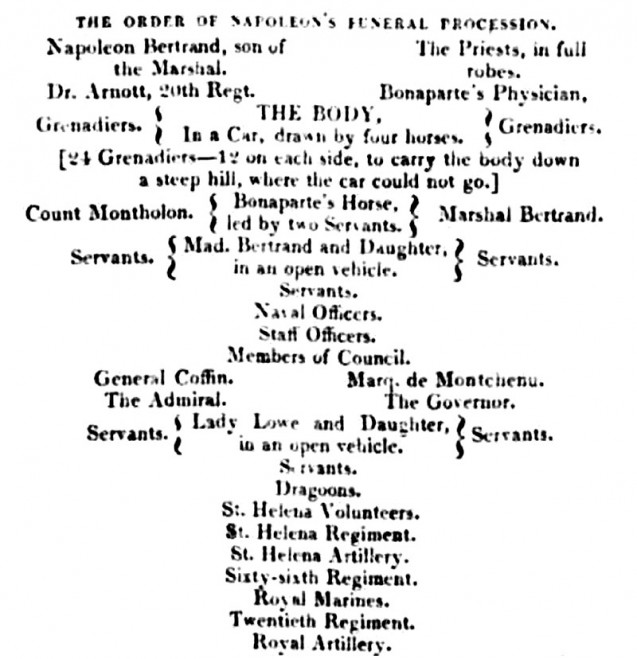

Napoleon’s Funeral

On the other hand, a fascinating personal account of the funeral was brought by Rosario and appeared in Bell’s Weekly Messenger on Monday 9 July 1821:

“Extract of a private letter dated St Helena May 15 [Note: Letter must have come on Rosario]

“Bonaparte was buried on the 9th in Sane Valley, a spot selected by himself, with the full military honours paid to a General of the first rank. His coffin was carried by grenadiers. Count Montholon and General Bertrand were the pall-bearers; Madame Bertrand with her family following. Next came Lady Lowe and her daughters [Note: “Daughter singular. Charlotte was married and had already left the island.] in deep mourning; then the junior officers of the Navy; the staff of the Army; last, sir Hudson Lowe and the Admiral brought up the rear. The 66th and 20th Regiments, the Artillery, Volunteers, and Marines, all in full 3,000 men, were stationed on the surrounding hills, about halfway up; and when the body was lowered into the grave, three rounds of eleven guns were fired by the artillery. His grave was about fourteen feet deep, very wide at the top but the lower part chambered to receive the coffin. One large stone covered the whole of the chamber. The remaining space was filled up with solid masonry, clamped with iron. Thus every precaution is taken to prevent the removal of the body, and I believe it has been full as much by the desire of the French commissioners [Note: Only one commissioner was left on the island, the French one.], as from the wish of the government of the island. The spot had previously been consecrated by his priest. the body of Bonaparte is enclosed in three coffins, of mahogany, lead and oak. His heart, which Bertrand and Montholon earnestly desired to take with them to Europe, was restored to the coffin, but it remains in a silver cup, filled with spirits. His stomach his surgeon was anxious to preserve, but that is also restored, and is in another silver cup.

As everything relating to so great a man must be of extreme interest, I should tell you, that after having attended his funeral I paid a visit to his residence. I was shown his wardrobe by Marchand, his valet, and a more shabby set-out I never beheld. Old coats; hats and pantaloons, that a midshipman on shore would hardly condescend to wear. But Marchand said, it was quite an undertaking to make him put on anything new, and then after wearing it an hour, he would throw it off, and put on the old again.

The last words Bonaparte uttered were ‘tête’ – ‘armée’. What their connexion was in his mind, cannot be ascertained; but they were distinctly heard about five o’clock on the morning of the day he died.

An officer’s guard is appointed to watch over his grave.

Bertrand, Montholon, and the rest of his household will return to England in the Camel store-ship, which sails in about a fortnight.

Drawings have been taken by Captain Marryatt, of the spot where Bonaparte lies buried, and also of the procession to his funeral.

Eleven rounds of 33-pounders were fired during the funeral.

He was put into a leaden coffin, in his plain uniform dress, star, orders etc. etc.; the leaden one was inclosed in two formed of mahogany; the outer coffin had plain top and side, black ebony round the edges and silver head-screws raised above the lid.

Napoleon is buried in a very romantic spot, situated in a valley near a place called Hut[t]’s Gate. I here relate the cause of his choice. When he first arrived Marshal Bertrand resided at Hut[t]’s Gate, until a house was built for him near the Ex-Emperor’s, who frequently visited the General’s family, and he (Bonaparte) would very often stroll down to a spring of excellent water (considered the best water on the Island), and order a glass to be brought that he might drink. Madame and Marshal Bertrand were always with him, and he several times said to them, “If it pleases God that I should die on this rock, have me buried on this spot,” which he pointed out, near the spring, beneath some willow trees.”