Enlightened Founders

All the «grands magasins» department stores have one thing in common, namely, one man of energy at the head. Boucicaut, Cognacq, and Chauchard were all owners of smaller sales establishments which failed. But they made immense fortunes with their larger enterprises: over a twelve-year period, the income of “Le Bon Marché” multiplied by 44, making Boucicaut worth 20 million francs. These captains of commerce were men of their time, under the influence of both liberalism and social Catholicism. Indeed, having worked their way up from the bottom, they had all learned the lesson that their employees had to be well housed and well fed, as this document (a Précis of the general rules and philanthropic measures taken on behalf of the employees at “Le Bon Marché” in 1894) shows.

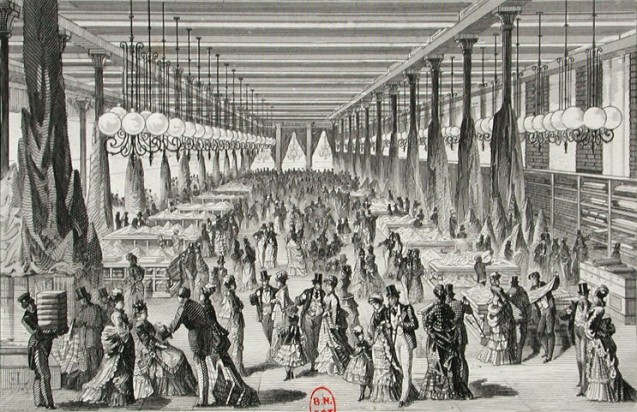

Modern architecture: Shops during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution in France, notably the railways, had a clear impact on the transport of textile raw materials, as did the use of sewing machines. With material now available in abundance, and transported easily and cheaply, the sales end of the chain required new structures to cope. The middle of the 19th century saw the demolition of Paris’s mediaeval shops and the creation of large commercial premises, which naturally benefited from advances in contemporary architecture. In many ways, it was Aristide Boucicaut, the founder of Bon Marché in 1852, who was the real and inventor of the Grand Magasin department store in France. Amongst other architects, he also called upon Gustave Eiffel as the architect in charge of the shop enlargement in 1869. Huge bay windows, coloured cupolas acting as lightwells, and cast iron rendered these news shops light and chic. The principles of ‘the department’ was also invented so as to provide a rational arrangement for the goods on sale: items were easier to buy simply because they were easier to find! Boucicaut, ever the visionary, brought a lift or elevator into his shops (it had first been exhibited in France Léon Édoux at the Universal Exhibition of 1867, though the very first was installed in one of his competitor’s shops, La Ville de Saint-Denis, in 1869). Boucicaut’s business sense also led him to build dormitories on the top floor of his shop for his unmarried female employees.

The Industrial Revolution in France, notably the railways, had a clear impact on the transport of textile raw materials, as did the use of sewing machines. With material now available in abundance, and transported easily and cheaply, the sales end of the chain required new structures to cope. The middle of the 19th century saw the demolition of Paris’s mediaeval shops and the creation of large commercial premises, which naturally benefited from advances in contemporary architecture. In many ways, it was Aristide Boucicaut, the founder of Bon Marché in 1852, who was the real and inventor of the Grand Magasin department store in France. Amongst other architects, he also called upon Gustave Eiffel as the architect in charge of the shop enlargement in 1869. Huge bay windows, coloured cupolas acting as lightwells, and cast iron rendered these news shops light and chic. The principles of ‘the department’ was also invented so as to provide a rational arrangement for the goods on sale: items were easier to buy simply because they were easier to find! Boucicaut, ever the visionary, brought a lift or elevator into his shops (it had first been exhibited in France Léon Édoux at the Universal Exhibition of 1867, though the very first was installed in one of his competitor’s shops, La Ville de Saint-Denis, in 1869). Boucicaut’s business sense also led him to build dormitories on the top floor of his shop for his unmarried female employees.

New commercial practices: the birth of marketing

Commercial premises were then entirely redesigned so as to reach the customer. The dismantling of the mediaeval-esque corporations made possible the emergence of new practices influenced by liberalism. Thus marketing was born. Boucicaut was again of the game, strong as he was in his sales experience, taking sales practices away from traditional door-to-door sales. He placed adverts in newspapers and sent catalogues by post. Furthermore, he adopted a practice of giving a fixed price per object (no longer deciding on the price according to what the salesperson thought the buyer would not balk at). Hence Printemps’ Latin motto became E probitate decus, “My honesty is a point of honour”. Items could be touched and tried on, and end of line items could even be sold for less. Sales people were trained to give customers taste advice, and they specialised according to their different departments. Bon Marché also pioneered other sales enticements, namely: a crèche for children allowing mothers freedom to browse the cases uninterrupted; a reading room for gentlemen; a tea room for rest and recreation – all designed to improve the shopping experience.

Commercial premises were then entirely redesigned so as to reach the customer. The dismantling of the mediaeval-esque corporations made possible the emergence of new practices influenced by liberalism. Thus marketing was born. Boucicaut was again of the game, strong as he was in his sales experience, taking sales practices away from traditional door-to-door sales. He placed adverts in newspapers and sent catalogues by post. Furthermore, he adopted a practice of giving a fixed price per object (no longer deciding on the price according to what the salesperson thought the buyer would not balk at). Hence Printemps’ Latin motto became E probitate decus, “My honesty is a point of honour”. Items could be touched and tried on, and end of line items could even be sold for less. Sales people were trained to give customers taste advice, and they specialised according to their different departments. Bon Marché also pioneered other sales enticements, namely: a crèche for children allowing mothers freedom to browse the cases uninterrupted; a reading room for gentlemen; a tea room for rest and recreation – all designed to improve the shopping experience.

A new target: the middle classes

![Où courent-ils?/where are they running to? [Au Grand Bon Marché]", poster by Jules Chéret 1875 © BNF](https://www.napoleon.org/wp-content/thumbnails/uploads/2015/10/487809_4-tt-width-637-height-247-crop-1-bgcolor-ffffff-lazyload-0.jpg) All the improvements were aimed at one socio-political group, a group which had emerged from the economic prosperity of the Second Empire, namely, the middle classes. No longer were luxury items just for the rich. The seamstresses at “Le Bon Marché” began by copying famous name clothing. Then, in the last quarter of the 19th century, French department stores began to have their own famous couturiers. Indeed, the feature was so successful that the shops produced their own fashion books (see here the 1910 edition). And whilst women were the primary customer target, men were not completely left out. Adverts were also aimed at a male clientele, and even at children, as this “Printemps” toy catalogue of 1884 shows.

All the improvements were aimed at one socio-political group, a group which had emerged from the economic prosperity of the Second Empire, namely, the middle classes. No longer were luxury items just for the rich. The seamstresses at “Le Bon Marché” began by copying famous name clothing. Then, in the last quarter of the 19th century, French department stores began to have their own famous couturiers. Indeed, the feature was so successful that the shops produced their own fashion books (see here the 1910 edition). And whilst women were the primary customer target, men were not completely left out. Adverts were also aimed at a male clientele, and even at children, as this “Printemps” toy catalogue of 1884 shows.

Conclusion

The Parisian ‘Grands Magasins’ were seen as models of innovation, in architectural, spatial, employment and client terms. And their influence was felt worldwide: in 1851, San Francisco witnessed the opening of the City of Paris Dry Goods Company (founded by the French brothers Émile and Félix Verdier); the Brussels branch of, “Le Bon Marché” opened in 1860; “La Rinascente”, in Milan, was built in 1865; and in London, “Harrods” performed a renovation in 1892 taking the Parisian “Grand Magasin” as its model. In fact, the “Grands Magasins” continued to develop long after the fall of the Second Empire, and they remain one of the greatest commercial innovations of the period, one which lasts to this day.

article by Marie de Bruchard, October 2015 (translation: Peter Hicks)