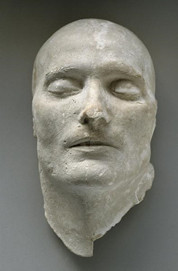

Bertrand’s Mask also known as the Bertrand Malmaison Mask (Musée National du Château de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau, France) © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau). Inventory N°: M.M.2000.25.175

The only mask whose provenance has been well identified: one of the first copies, possibly the first cast made from the original imprint made of Napoleon’s face after his death.This mask was made in London for Countess Bertrand. On the inside, there is an inscription in Italian: A l’impareggiabile merito di madame Bertrand, Antommarchi, 27 agosto 1821. (A homage to Madame Bertrand’s peerless merit, 27 August 1821).A note by Bertrand’s – dated 1 September 1821 – corroborates the existence of a mask made from the cast fabricated on St Helena.Madame Hortense Brayer, daughter of Count and Countess Bertrand, inherited this mask, which she then gave to Prince Victor as a gift.It was given to the Musée National du Château de Malmaison in 1979 by the prince Napoleon Victor and his sister, the Countess de Witt, and has been kept there ever since.

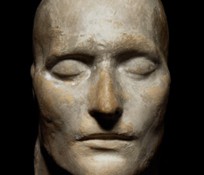

The Antommarchi-Azhémar Mask also known as the Antommarchi Malmaison Mask (Musée National du Château de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau, France) © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) / André Martin. Inventory N°: M.M.40.47.7284

The Antommarchi-Azhémar Mask also known as the Antommarchi Malmaison Mask (Musée National du Château de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau, France) © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) / André Martin. Inventory N°: M.M.40.47.7284

This mask comes from the South-American branch of the Antommarchi family. Francesco Antommarchi died in Cuba with no direct descendants, so the mask came into the possession of his half-brother, also living in South America. In 1921, the mask (and the box containing it) was given to the Musée National du Château de Malmaison by Edouard Azémar, grand-nephew of Doctor Antommarchi. It was bought by the French state in 1944.The Malmaison Mask could have been the first made on St Helena using Burton’s cast; according to some historians, proof of this lies in the rough clay that was used to make the central part of the mask.

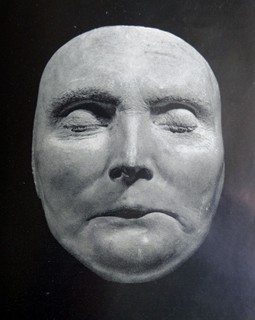

The Antommarchi-Burghersh Mask (Musée de l’Armée – Hôtel des Invalides, Paris). © Musée de l’Armée. Inventory N°: d.f. 3/3

The Antommarchi-Burghersh Mask (Musée de l’Armée – Hôtel des Invalides, Paris). © Musée de l’Armée. Inventory N°: d.f. 3/3

The story of this mask runs as follows: It was destined to be sent to the Florentine sculptor Canova so that he could use it as the basis for a sculpture. It then supposedly came into the hands of Lord Burghersh, an English minister also residing in Florence and who was known by Antommarchi. According to other versions of the story, the mask might have even belonged to Wellington… In 1915, following the late publication of the testimony of the upholsterer from Jamestown, Andrew Darling, who mentioned the sculptor Canova as the mask’s first recipient so that the latter could make a marble bust from it, a few days later, the precise location of this mask was revealed via the letters section of The Times to be the house of the heirs of Lord Burghersh in England.Like the Azhémar mask, this copy is made up of several pieces, a fact that would suggest (for partisans of this mask) that the central part could be the actual imprint taken by Dr Burton on the night of 7 to 8 May 1821, at Longwood. The mask was bought in 1951 by Eugène de Veauce in an auction in Ascot, England. It is presented at the Musée de l’Armée at Invalides in Paris since November 1953. It was bought by the Fondation Napoléon in 1989, but given back to the museum as a gift.

Two masks entrusted to Reverend Boys (Sankey Mask and Boys Mask) (The Sankey Mask is on long-term loan to the Maison Française at the University of Oxford and the Boys Mask was sold in London in 2013). © Bonhams

Two masks entrusted to Reverend Boys (Sankey Mask and Boys Mask) (The Sankey Mask is on long-term loan to the Maison Française at the University of Oxford and the Boys Mask was sold in London in 2013). © Bonhams

The notes accompanying these masks indicate their owner as Reverend Richard Boys (1785-1867), vicar on St Helena from 1811. The Sankey Mask was referred to for the first time in an article that appeared in The Times in 1915. It bears the name of one of Reverend Boys’s grandsons. It is on long-term loan to the Maison Française of the University of Oxford. According to George Leo de St. M. Watson, author of The Story of Napoleon’s Death-Mask, published in 1915, but without the support of any authenticated sources, the artist William Rubidge supposedly helped Antommarchi use the central part of the mould to make a complete mask adding a neck, ears (incomplete) and a forehead. Watson’s friend, Arnold Chaplin, in the second edition of his book A St Helena Who’s Who (published in 1919), supported this version of events and also added a note about the painter, Rubidge. However, this has not been confirmed by any source: Rubidge died very young and did not leave any memoirs or letters. The Reverend Boys never publicly mentioned his masks during his lifetime. As for the Boys Mask, the first reference to this appeared in a letter written by Dr Leonard Boys (grandson of Boys, and owner of the mask) published in The Times on 4 December 1929. The mask was sold in London in 2013 for 170,000 pounds (198,000 euros). Acting on the advice of experts, the culture minister placed an export ban on the mask and tried (in vain) to raise enough money to buy it back. A subsequent appraisal in March 2016 cast doubt on the mask’s authenticity and the export ban was lifted.

Two masks: Gilley 1 et Gilley 2 (Maison Bonaparte Museum, Ajaccio). © RMN-Grand Palais (Maison Bonaparte) / Gérard Blot

Two masks: Gilley 1 et Gilley 2 (Maison Bonaparte Museum, Ajaccio). © RMN-Grand Palais (Maison Bonaparte) / Gérard Blot

The first of the two Gilley masks appeared in 1956. The supposed authenticity of this mask derives from its first owner Colonel Gilley, duty officer on St Helena. However, this name does not appear in the list of officers having stayed on the island in the 1820s. It is most likely that he bought the mask on a later visit on St Helena. The second Gilley Mask appeared in 1961. The handwritten note accompanying the mask indicates that it was given to Major Gilley in 1830 by Hudson Lowe’s brother, when both men were officers at the barracks in Malta and later in Gibraltar. (However, Hudson Lowe’s official biographies note that he only had a sister, not a brother). Both of the masks are kept at the Maison Bonaparte in Ajaccio (Corsica). The first Gilley Mask was given to the museum in 1991 by Paul Brès, and the second by Eugène de Veauce.

Both of these masks are presented as casts made on the island of St Helena.

The Exeter Mask (Exeter Central Library, Great Britain) © Exeter City Library

The Exeter Mask (Exeter Central Library, Great Britain) © Exeter City Library

This mask’s line of descent runs as follows: it was first sold by John Gawler Bridge to the antique-dealer Maggs in 1911, who then sold it to Heber Mardon, a collector of Napoleonica. Mardon then donated it to Exeter Central Library in 1925. Doctor Arnott is said to have been the first owner of the mask. According to this interpretation of events, he took a wax mask and a plaster mask back from his stay on the island. Those who support this interpretation claim that the mask was made on St Helena.

Le Noverraz Mask (Musée historique de Lausanne) ©Musée historique de Lausanne

Le Noverraz Mask (Musée historique de Lausanne) ©Musée historique de Lausanne

A female descendant of a possible relative of Jean-Abrahm Noverraz (Swiss-born servant of Napoleon who was part of his household staff on St Helena) donated this mask to the Musée Historique de Lausanne in 1997.

The Rusi Mask (Royal United Service Museum), then Corso (Private Collection)

The Rusi Mask (Royal United Service Museum), then Corso (Private Collection)

This mask belonged to Charles Alder (rather than Adler) in 1939. He claimed to have bought it from a man called Louis-Charles de Bourbon, who in turn claimed to have acquired it from the Prince d’Essling, even though the latter firmly denied the presence of such a mask in his collections. Mr and Mrs Alder donated it to the Royal United Service Institution in London (RUSI) on 5 May 1953. (The RUSI was founded in 1831 by the Duke of Wellington for the study of military science). Contrary to speculation that the mask was misappropriated by a curator in 1973, it was actually auctioned off at the beginning of the 1970s while the institution was being set up in new premises. The note presenting the piece of work kept at the RUSI bears the letter ‘A’ for auction but does not give a precise date for the sale of the mask. In 1986 the company Forman of Piccadilly Limited based in London sold this mask or a very similar mask to the American collector Corso. The latter then sold it again in 2004 (the auction took place at Christie’s in New York on 2 December 2004) to an American purchaser for a little over 13,000 dollars. Christies was careful about indicating the mask’s origin, noting its resemblance to that kept at the RUSI until the 1970s.

© Fondation Napoléon

The “Lebendmaske” Mask (Rollettmuseum, Baden, Austria)

The “Lebendmaske” Mask (Rollettmuseum, Baden, Austria)

The note describing this mask in the Rollettmuseum indicates that it was moulded from the Emperor’s face while he was still alive as a gift to his son, the King of Rome. Antommarchi possibly gave it to Marie-Louise, who then gave it to the tutor of the ex-Empress’s children. The latter then gave it to Dr Rollett as a present, during his stay in the Austrian thermal town of Baden-Baden. No source, testimony or letter mention the fabrication of a mask from of Napoleon’s face while he was still alive during his two exiles. Nor are there any references to a mask given to Marie-Louise by Antommarchi. It was not until much later, between 1886 and 1887, that this mask appeared in the museum inventories, and even then, it appeared under the term ‘death mask’ as opposed to a mask made from Napoleon’s face while he was still alive.

©Rollettmuseum, Baden-Baden, Austria, Urban Collection

The masks commercialised by Antommarchi

The masks commercialised by Antommarchi

Dr Burton’s death in 1828 liberated Antommarchi from the threat of a trial for theft and breach of trust, allowing him to commercialise the mask. In 1833 Antommarchi established a fund for a mask to be made of either plaster or bronze. Antommarchi migrated to America in 1834, then from there to Cuba, where he died. He sold all the rights to the reproduction of his works to the founders L. Richard and E. Quesnel from Paris, arranged the fabrication of bronze copies of the mask. When Antommarchi died in 1836, the Susse Brothers house bought the rights to commercialise the mask. A number of copies of the mask were made during the Second Empire and at the beginning of the 20th Century.

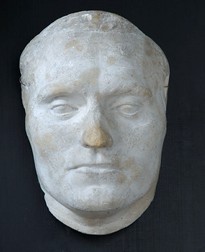

© Fondation Napoléon. Plaster mask. With “cushion” Inventory N°: 1179