Napoleon would never read the letter. On 14 July, Hortense was in Baden in the canton of Aargau undergoing a treatment for a rheumatic fever. She was joined her there by her former teacher, Madame Campan, and the Abbé Bertrand. It was there that she received the painful news of Napoleon’s death on the faraway island of St Helena. Hortense then left for the Abbey of Einsiedeln in the canton of Schwyz, which is where she always went when she needed peace and quiet. Madame Campan and the Abbé continued their journey directly to Lake Constance. Shortly afterwards, Hortense received from her friend, the Duchess of Ragusa, a bracelet with a central stone in the shape of a coffin bearing the words “Mon fils – tête de l’Armée – France!” [“My son, head of the army, France!”], which are said to have been the last words spoken by the Emperor as he breathed his last.

Shortly after the news of his death was announced, Hortense received a long letter from General Bertrand, followed by a visit by General Gourgaud. Could it have been on this occasion that he gave Hortense a cutting taken from one of the weeping willows on the island of St Helena? The inscription on a black and white stereoscopic photograph, taken at the end of the 19th century by the photographers Ferrier and Soulier, shows that it was still known at that time that Gourgaud had brought this willow back from St Helena to be planted at Arenenberg.

At the foot of this tree Hortense had placed a rectangular stone, a tombstone. Was there an inscription? Nearby a spring flowed towards Lake Constance. Everything was reminiscent of the so-called ‘Geranium Valley’ in St Helena. Hortense always celebrated the cult, the legend of Napoleon. She liked to show her souvenirs to her guests – Alexandre Dumas and Chateaubriand talk about them in their memoirs -: the famous hat; the letters from Napoleon to her mother, Empress Josephine, which she kept in a folder marked with a J and an N and which she had published in 1833; the belt worn in Egypt; the wedding ring; the talisman of Charlemagne; and the painting that so impressed Alexandre Dumas, Gros’s General Bonaparte on the bridge at Arcole. She kept this cult for herself and for the Emperor’s supporters, but above all for her son, for Louis Napoleon, whom she hoped would one day ascend the French throne, of whom Napoleon had said shortly before his departure for Waterloo: “He will have a good heart and a beautiful soul … he is perhaps the hope of my race”[1]. In 1834, the painter Félix Cottrau painted a portrait of Hortense sitting at her upright piano in the chapel overlooking the lower lake. In it the artist set in full view, brightly lit, the Talisman of Charlemagne as the clasp of the cloak she was wearing, thus showing Hortense as the mother of the next generation on the throne. She would not live to see Louis Napoleon become “Napoleon III”.

In the 20th century, many of these souvenirs of the Napoleonic legend were to disappear from Arenenberg: the hat, the talisman (now on display in the Palais du Tau in Reims, donated by Empress Eugenie in 1919), the letters (they are at the French National Archives). Only the painting by Gros remained hanging in the parlour with its tented ceiling, reminiscent of the “Salle du conseil” at the Château de Malmaison. At that time, traces of Hortense’s devotion to Napoleon disappeared not only from the house but also from the grounds, because in 1906, with the donation of the property by Empress Eugenie to the canton of Thurgau, the part of the park where “Napoleon’s tomb” was located was replaced by vineyards. All that remains of it are images.

As part of the commemorations of the bicentenary of Napoleon I’s death, the Napoleonmuseum has decided to revive this place of Napoleonic remembrance: a willow tree has been planted and a plaque inscribed with an N has been placed near the tree.

Also to mark the bicentenary and the reconstitution of this place of remembrance, the winegrower Peter Mössner is preparing a special “cuvée” (Pinot Noir, Régent, Maréchal Foch and Léon Millot). Its name? “The Tomb of Napoleon”.

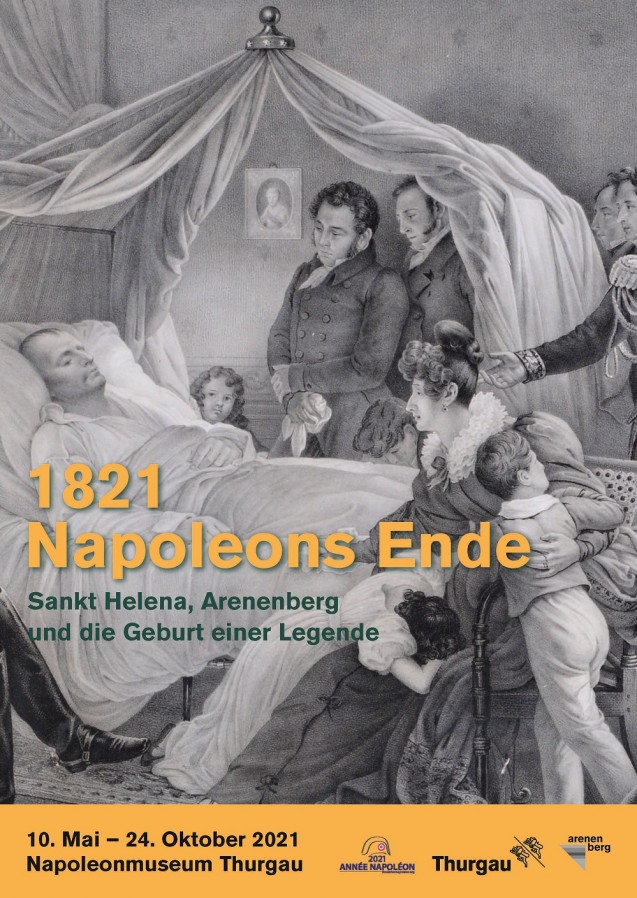

Also at Arenenberg this year will be a temporary exhibition “”1821 – Napoleons Ende – Sankt Helena, Arenenberg und die Geburt einer Legende” (1821 – The Death of Napoleon – St Helena, Arenenberg and the Birth of a Legend) which will be held from 10 May to 24 October.

Christina Egli is curator of the Napoleonmuseum-Thurgau a partner of the 2021 Année Napoléon label. (translation RY)

[1] Stéfane-Pol: La jeunesse de Napoléon III. Paris, 1902, p. 8