The Crimean War, which lasted from 1853 to 1856, marked the return of France to the military and diplomatic forefront of Europe after a long period of absence post-1815 – the Spanish campaign and the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s excepted. The Congress of Paris, which brought the Crimean War to a close and which took place in the brand-new Quai d’Orsay offices (inaugurated only a few months earlier), partly washed away the humiliation of the Congress of Vienna.

This war has, however, been ignored by French historiography for many reasons, not least because of the scorn with which the Second Empire was long regarded in France. In 1995, a publication by Alain Gouttman put things right, but his book was very much a battle history and was not in the end a catalyst for other books. The slowness of French historians to show an interest in the Crimean War was all the more regrettable since historians outside France, particularly English-language scholars, have long been writing on this subject, not only in general monographs (Orlando Figes, 2010) but also in specific new fields of research, often highlighting the role of Florence Nightingale and her team of nurses at the hospital in Scutari: focusing on the areas of health and the body (Jane Shuter, 2003), gender (Helen Rappaport, 2007), and representations (Stefanie Markovits, 2009).

But this has by no means exhausted the complex subject of the Crimean War. The conflict deserves our interest because, along with the Italian War (1859), the American Civil War (1861-1865), and the three wars led by Prussia under Bismarck (1863-1871), it constitutes a major turning point in military history, marking the transition between the wars of the French Revolution/Empire (themselves still very much influenced by the conflicts of the Ancien Régime, despite also bringing with them a certain modernity – recourse to conscription, the importance of the army corps, the unprecedented role of the national imagination) and the First World War, characterised by the total commitment of the States involved.

In some ways, the Crimean War, too, was already a world war. Far from being limited to the shores of the Black Sea, this war, which in France at the time was sometimes called the “Guerre d’Orient” or the “Eastern War”, affected Eastern Europe, Asia, and even the Pacific.

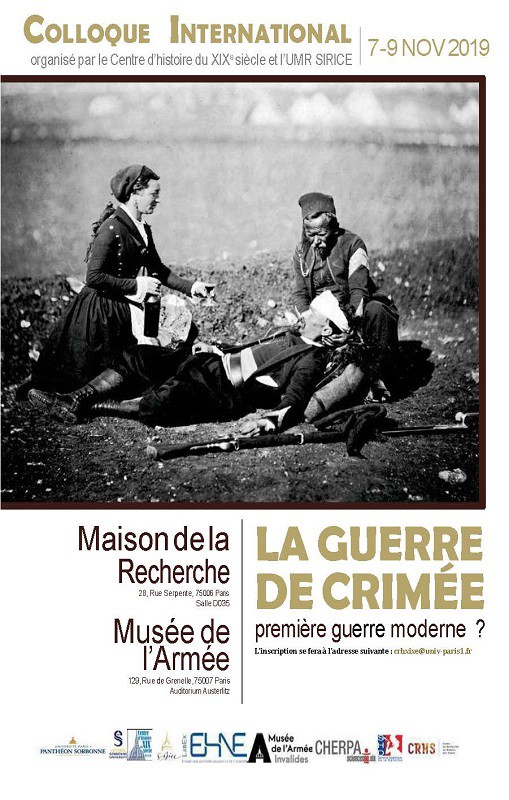

It was also a modern war, witnessing innovations in technology (steam-powered battleships, rifled guns, explosive shells, trenches), logistics (the use of the railway and the telegraph), and diplomacy (the establishment of the concert of nations and the birth of international maritime law).

This war also marks the first appearance of the (later consubstantial) link between the State, the army and the nation. During the Second Empire, a law was passed (in 1855) that put an end to the lottery-based conscription system and made it obligatory for those exempt from conscription to pay an exoneration charge to the State. Military widows and orphans were paid a pension. War memorials were built throughout France, on a scale never before seen. Men of all military ranks, from the commander-in-chief, the Maréchal de Saint-Arnaud, right down to the ordinary soldier, were celebrated as heroes whilst the enemy was demonised on a large scale. The bond between the State, the army and the nation was celebrated not only on the Saint Napoléon or Emperor’s Day (15 August) but also during the festivities that followed the taking of Sebastopol. Public engagement in the conflict also came via official communiqués, photographic reports, and the publication of maps representing the theatres of operations and troop movements. Last but not least, the government also closely monitored fluctuations in public opinion. Similar phenomena occurred, to varying degrees, in all the other warring nations: the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Piedmont and the Ottoman Empire. However, comparative study is lacking in the research on this war, as historians often remain prisoners of their national historiographical concerns. The transnational dimension is also missing. For example, too little attention has been paid to the trajectories of combatants who served in foreign armies, or who even changed sides in the middle of the conflict.

The Crimean War is thus a world war, a modern war, and an important milestone in the transition to total war. It is for all these reasons that Marie-Pierre Rey, Jean-François Figeac and I devoted a symposium to it which took place on 7, 8 and 9 November 2019 at the Sorbonne and the National Army Museum in Paris. The event welcomed thirty-six speakers from eleven different countries (France, UK, Turkey, Russia, Italy, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, Belgium, Morocco and Tunisia), exploring eight different themes: the concert of nations, the transformation of diplomatic practices, a new way of waging war, war and health, the interstitial space between the front and the rear, the mobilisation of public opinion, representations and images of war, and the war in collective memory. The proceedings of this symposium, which drew an audience of nearly 200 and gave rise to rich debates, will be published in the course of the year 2020.

Éric Anceau (Sorbonne University, SIRICE [Sorbonne-Identités, relations internationales et civilisations de l’Europe]), January 2020