Bombay had carried the Scottish passengers Major Ludovick Stewart of the 24th regiment of foot and his wife Margaret (née Fraser). Las Cases in the Mémorial tells us that, on 10 November 1815 at “The Briars”, Napoleon met and spoke with the beautiful twenty-year-old Mrs Stewart in the company of Mrs Balcombe. The Major too might have met the Emperor, though this is not certain. The 21 December 1815 issue of The Courrier noted that Napoleon had taken “several officers of the Bombay by the hand and conversed with them for a long time”, as did an anonymous letter (said by The Times of 17 January 1816 to be by a son to his father in Edinburgh) published without title in the London Star on 16 January 1816, whilst the Edinburgh Advertiser of 2 January 1816 had noted the opposite, namely that “the officers of the Bombay experienced great disappointment in not having an opportunity of seeing [Napoleon]” – maybe some did and some didn’t. But we know that Captain Hamilton of Bombay did, on 11 November 1815, the day before setting sail, because he wrote so in a private (unpublished) letter, in which he referred to Napoleon’s hosts’ daughter (in fact, Betsy Balcombe) as a ‘pert young hoyden’ and a ‘romp’.

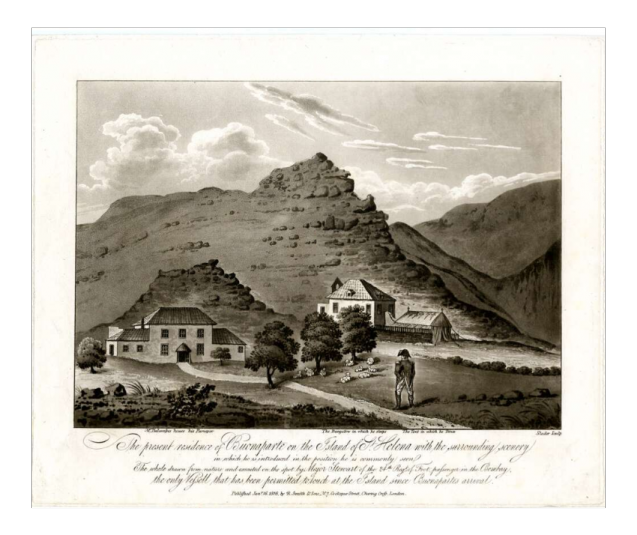

Regardless, Ludovick must at least have gone up to “The Briars” while on the island because, since he was a relatively good artist, he had published on 16 January 1816 with R. Smith and Sons in London an engraving of “the present residence of Buonaparte […]”, including a very accurate rendition of the pavilion with the tent pitched outside.

Perhaps most interestingly of all, the letters brought by Bombay and Ariel mark the beginning of the legend of Betsy Balcombe. The Edinburgh Advertiser noted “the ci-devant Emperor spends most of his time in various amusements with the daughters of his host, who were considered interesting young women. In the evening […] ‘the party plays at cards for sugar plums’”. As for the anonymous letters dated 20 and 24 November 1815 brought on HMS Ariel (published in the London Star on 18 and 16 January 1816, respectively), there really is not much doubt as to William Warden’s authorship given they report medical matters and are marked as from Northumberland (Warden was surgeon on Northumberland). Remarkably, these accounts were not to be included in Warden’s book (first published in November 1816).

In the 20 November letter, Warden remarked that Balcombe’s daughters (Jane and Lucia Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Balcombe) were “extremely well educated, and under the age of seventeen” (in fact 13 and 15 respectively); “both speak French, and I am satisfied they afford him [Napoleon] very great consolation”. “Frequently of an evening, he [Napoleon] joins Balcombe’s family, and with the girls […], he joins in a party of whist, when he tries to revoke or cheat, and when discovered (by the arch, youngest lass [Betsy]) he laughs immoderately’. The anonymous, son-to-father letter first published in the London Star on 16 January 1816 (mentioned above) – since this letter came on Bombay it must refer to events that occurred before 12 November -, described the girls as follows: “Mr B. has two smart daughters, who talk the French language fluently, and to whom he [Napoleon] is very much attached – he styles them his little pages. There is a number of little stories of the innocent freedoms they take with him, and how highly he is diverted by it.”

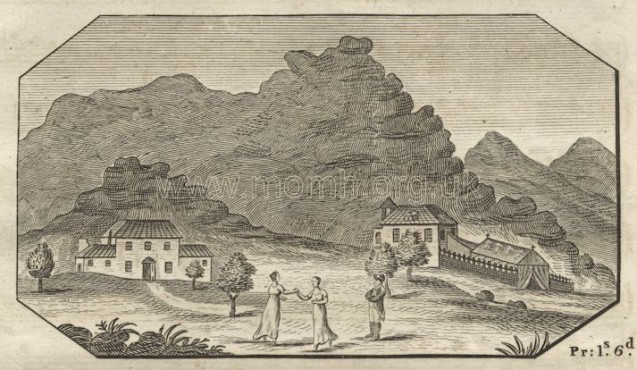

As if this weren’t enough fame, the start of the legend of Betsy Balcombe was cemented by the publication in London of Charles von Boigelet’s The St. Helena Waltz, first announced in the Morning Chronicle on 1 March 1816. The piece is dedicated to “the Miss Balcombes” and has for a frontispiece a reworking of Ludovick Stewart’s view of “The Briars”, but with the tiny figures of Jane and Betsy added in the garden, dancing before the Emperor.

Listen to the waltz played on the piano by Peter Hicks

Follow the score. (with thanks to the Museum of Music History).

Peter Hicks (October 2020)

International Affairs Manager at the Fondation Napoléon