Malta and the Knights Hospitaller of St John

Any discussion of the 1798 taking of Malta, the subsequent siege and liberation must begin bearing in mind the two fundamental events of the ten years immediately preceding the annexation of Malta to France. First, on 30 July 1791, the powers that were declared the denationalisation of every French citizen affiliated to a chivalric order established outside France. Now Malta since the early Middle Ages had been the home of the Knight of Malta, a chivalric order of which by 1789 two thirds were French… and exceedingly wealthy. Second, on 19 September 1792, the Legislative body met to put the wealthy domains (or ‘Commanderies’ as they were called) of these men at the disposal of the nation. At one fell swoop the Order of Malta lost half of its revenue. This caused a definitive rupture between Malta and France.

France gone, other Nations become interested

Nor were other nations slow in coming forward to the aid of this small island so well situated with regard to trade with the Levant, plumb in the centre of the Mediterranean. Britain with its naval base on Minorca offered its ‘protection’. The Tsar Paul I offered final assistance to the Order, raising money from Polish ‘Commanderies’ and founded the Grand Priory of Russia (1797). Austria too with its position in the Adriatic and its privileged relationship with Naples had designs upon the Mediterranean – perhaps even the Grand-Master Hompesch was pro-Austrian.

The Directory decides to take Malta

It was in this context that on 26 May 1797 Napoleon suggested to the Directory the conquest of Malta. The island, it appeared to him, was an important pawn in the projected Mediterranean strategy, whose final aim was to use Egypt as a stepping stone to reach and destroy British interest in India.

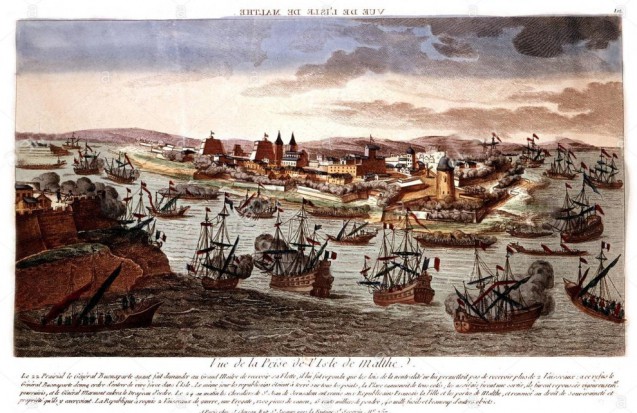

The Invasion

On 9 June, the gigantic Egyptian invasion fleet (numbering about 50,000 men), commanded by Admiral Brueys, in effect set siege on Malta. As a result of the passivity of the inhabitants and the few troops available to Grand-Master Hompesch (332 knights, 3,600 men in the harbour and about 13,000 militia men from the countryside around), the siege was not to be more than more than a few cannonades. On the morning of the 10th, French forces attacked simultaneously at four different spots. Desaix, after securing Marsaxlokk Bay, was to cross the Cottonera lines and if possible take on of the principal gates of Valetta by assault. Vaubois, the future governor of the island during the two year siege, was to land with his men on the coast stretching between Sliema and Qawra Point, to move in land and take Mdina and the surrounding villages. D’Hilliers was instructed to take St Paul’s and Mellieha Bays and to advance to Mdina and the Madliena Heights. Finally Reynier was to occupy the poorly-defended island of Gozo. By the afternoon all apart from the Grand and Marsamxett Harbours and Fort St Lucian were in French hands. On 12th, the Hompech capitulated.

Modernity for feudal Malta

In the six days which followed the surrender and the departure of Bonaparte for Egypt, a civil code was laid down for Malta. Slavery was abolished and all Turkish slaves were freed. All feudal rights and privileges were abolished. A new administration was created with a Government Commission, twelve municipalities were formed. Alongside these twelve judges were nominated. Public finance administration was arranged. Public education was organised along principles laid down by Bonaparte himself, providing for primary and secondary education. Fifteen primary schools were founded and the university was replaced by an ‘Ecole centrale’ in which there were eight chairs, all very scientific in outlook: notably, arithmetic and stereometry, algebra and stereotomy, geometry and astronomy, mechanics and physics, navigation, chemistry. Furthermore sixty children, aged 9-14, from Malta’s richest families were to be sent to Paris to be educated in ‘colleges’ in France.

In the six days which followed the surrender and the departure of Bonaparte for Egypt, a civil code was laid down for Malta. Slavery was abolished and all Turkish slaves were freed. All feudal rights and privileges were abolished. A new administration was created with a Government Commission, twelve municipalities were formed. Alongside these twelve judges were nominated. Public finance administration was arranged. Public education was organised along principles laid down by Bonaparte himself, providing for primary and secondary education. Fifteen primary schools were founded and the university was replaced by an ‘Ecole centrale’ in which there were eight chairs, all very scientific in outlook: notably, arithmetic and stereometry, algebra and stereotomy, geometry and astronomy, mechanics and physics, navigation, chemistry. Furthermore sixty children, aged 9-14, from Malta’s richest families were to be sent to Paris to be educated in ‘colleges’ in France.

The siege of two years

But after Bonaparte’s departure Vaubois was left in charge, and things began to go wrong for the French. Acceptance of the French on Malta was by no means unanimous. There were guerrilla attacks by the locals. Then three weeks after Bonaparte’s departure there was the insurrection of 2 September 1798. Encouraged by British victory at the battle of the Nile, the mob broke up a sale of gold and silver items, tapestries and sacred objects designed to raised money for the French authorities. The Maltese officials who were to run the sale retired to Valetta. On the afternoon of the same day, Masson the commander of Mdina was involved in an exchange of insults with a mob in Rabat. He was murdered on the spot and his corpse was thrown out of a window. At dawn on the following day Mdina was captured by insurgents. French reinforcements for Rabat numbering 250 men were routed. The gunpowder magazine in Cottonera were seized, Gozo was overrun. By 4 September the French forces in Malta and nearly 40,000 city dwellers were corralled behind the long walls protecting the Grand and Marsamxett Harbours., the rest of the country was in the hands of the Maltese rebels. Requests to help rid Malta of the French were sent to Ferdinand the King of the Two Sicilies and to Nelson. Nelson proved to be more forthcoming by sending a Portuguese squadron of four ships of the line and two frigates under the command of Marquis Pinto-Guedes de Nizza Reale. The blockade had begun. In October 1798 Nizza Reale was replaced by captain Alexander Ball and he was to keep it up for the following two years. The only break in this apparent stalemate was when the French on the small island of Gozo surrendered with full military honours on 28 October. Similarly two ships managed to break the blockade. All in all Vaubois’s resistance to the siege was tenacious and noble. By a combination of expelling locals, extracting forced loans from wealthy Maltese and rationing supplies and ammunition, Vaubois managed to withstand two years on rations for only seven months. It was only on 5 September, 1800, with the last crumb of bread gone, that he reluctantly capitulated to the British navy.

Aftermath

Despite attempts to return Malta to the knights, the island was to remain under British control forming – along with Minorca – central points for the British navy in the Mediterranean, and providing launch bases for the expeditions against Egypt (1801) and the Ionian islands (1809-1814). It was also used as a trade counter for goods from the Orient, providing a source of contraband against the continental system. Malta was to remain British as result of the treaty of Paris, 30 May 1814. But in the minds of the Maltese people the resistance to the occupying French was to remain as one of the most glorious pages in their long and eventful history.

Bibliography

Dictionnaire Napoléon, (ed. J. Tulard), Fayard, 1989, pp. 1125-6

Masson, Ph., ‘Napoleon and England, part 1’, La revue du S.[ouvenir] N.[apoléonien], 400

Spillman, G., ‘L’Armée d’Orient de Toulon au Caire’, La revue du S.[ouvenir] N.[apoléonien], 304, pp. 2-6