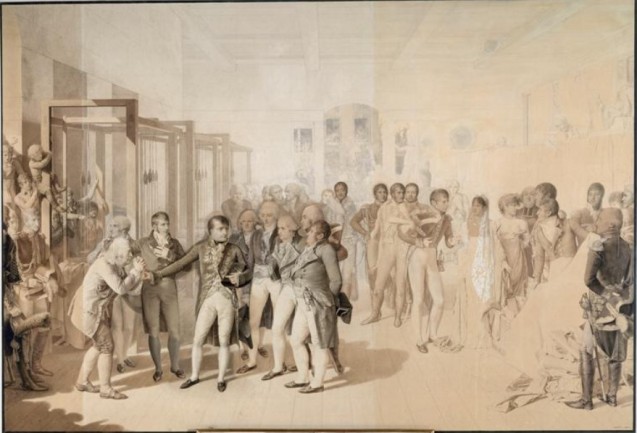

Of course, far be it from me to meddle in matters that only concern the people of Rouen, but it is surprising that in order to honour Madame Halimi (whose links with Rouen are unknown to me), they had to have a go at Napoleon, whose statue has been part of the urban fabric of the city for the past 135 years. Nor was this the result of a whim of Napoleon III: Napoleon I really was a benefactor of the place. He always treasured Rouen and in terms of its manufacturing capabilities considered it a place the highest order. He saw it becoming the “grand port de Paris” fed by the magnificent “avenue” of the Seine. He even visited Rouen twice (1802 and 1810), inspecting the industries (perked up by the general peace of 1802 and later given a further boost by the Continental Blockade of 1806), having a bridge built over the Seine and ordering other constructions. The famous painting by Isabey showing him visiting the Sevenne brothers’ velvet manufactory is well known*. As a further mark of the Imperial regime’s interest in the city, Marie-Louise returned alone in 1813 to lay the first stone of the Pont Corneille bridge. Rouen was so important in Napoleon’s eyes that he only ever appointed “solid” prefects in whom he had great confidence, such as Beugnot, Savoye-Rollin and Stanislas de Girardin. He was similarly attentive in choosing the four successive mayors, generally important local businessmen. On 11 Brumaire, An XI (2 November 1802), in Rouen, Napoleon wrote to his brother Joseph: “This town gives me moving tributes of attachment to me. Everything here is comforting and beautiful to see. I really do love Normandy, so beautiful, so fine. This is the real France*.”

On all these questions, I would recommend that the elected representative and citizens of Rouen read the work of Jean-Pierre Chaline and his colleagues on their town during the Consulate and the Empire. They will realise that the project unveiled by the mayor cannot be as a result of any misdeeds that Napoleon may have performed with regard to this city, a city for which furthermore the mayor’s team have a duty of remembrance. As for Gisèle Halimi, whilst there is no doubt whatsoever that she deserves a statue (but what would she have thought about that idea?), maybe other prestigious parts of the town could have been set aside, such as the new neighbourhoods currently under construction. But, of course, this is not simply about the destination of several tons of copper or bronze, regardless of the historical figure in question. It looks much more like local political alliances as the source of the project, where promises were made to a majority amongst whom figure certain deniers of French history and French memory. Elsewhere in France, the colleagues of these people are having a go at Christmas trees, the “Patrouille de France” (the French national air display team), the Tour de France, indeed anything related to what they call “the old world”. […] The fact that this business is being dealt with by the town hall official responsible for gender equality and immigration (rather than culture and heritage) is a strong sign of what’s actually going on. The first press releases spoke not only of the feminism that led to the choice of Gisèle Halimi, but also of the re-establishment of slavery. Let’s be clear here, if Rouen had had a statue of Colbert, the manoeuvre would have been about that statue.

It is part of our mission here to preserve heritage. So of course we’re worried about this sort of thing. With the approach of the 2021 bicentenary, we’re going to be on our guard, because other situations like this will arise. As for the people of Rouen, all we can do is to urge them to take part in the much-vaunted consultation, hoping it’ll take place as fairly as possible.

Historian and Director of the Fondation Napoléon

15 September 2020

* Correspondance générale de Napoléon Bonaparte, Fondation Napoléon/Fayard, tome 3, letter 7259, p. 1145.

visiting the manufactury of the Sévène brothers in Rouen (November 1802), by JB Isabey, 1804

© RMN-GP, (château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot