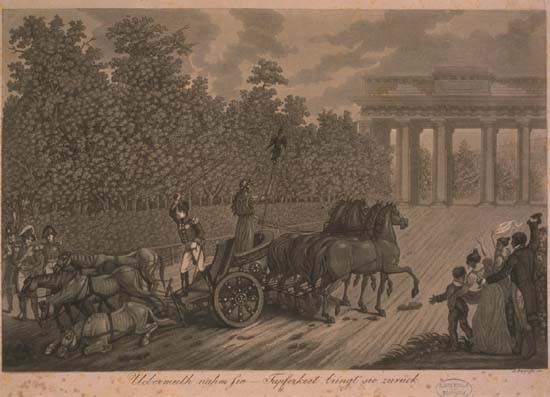

On 27 October, 1806, after the victories at Iéna and Auerstädt two weeks earlier, Napoleon rode in triumph into Berlin passing under the Brandenburg Gate. It would appear that the four-horsed chariot caught his eye, because Vivant Denon, director of the Musée Napoléon (the museum which was to become the Louvre) gave the order for the work to be brought back to Paris. Denon was travelling with the Grande Armée and it was his role to oversee the taking of art treasures and to arrange for their transport. Indeed, according to Johann Gottfried Schadow (1764-1850), the then rector of the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts, the French generals used to call Denon the 'voleur à la suite de la Grande Armée' (thief on the coat tails of the Grande Armée). At the end of November of the same year, Denon paid a visit to Schadow (also sculptor of the chariot grouping) to see about the logistical problems of bringing the work back to Paris. Schadow wrote in his memoirs that they had to contact Emanuel Ernst Jury, the metalworker from Postdam who had assembled the group back in 1793 as a monument to peace.(1) Twelve enormous crates were made and packed with almost indecent haste. In fact, two of the horses had already been taken down by 3 December, and the whole cargo was to be dispatched by water to Paris on 21 December, 1806.(2)

The crates arrived at their destination six months later (16 June, 1807), unfortunately it would appear somewhat damaged, in that Denon asked for a space large enough in which to open them to perform the necessary repair work. He wrote to the emperor's architect, Fontaine, asking permission to use the Orangery at the Louvre for three months as a temporary storage place – just sufficient time to make the repairs and to decide on a definitive resting place for the imposing group.(3)

The crates arrived at their destination six months later (16 June, 1807), unfortunately it would appear somewhat damaged, in that Denon asked for a space large enough in which to open them to perform the necessary repair work. He wrote to the emperor's architect, Fontaine, asking permission to use the Orangery at the Louvre for three months as a temporary storage place – just sufficient time to make the repairs and to decide on a definitive resting place for the imposing group.(3)

Back on the campaign trail, three weeks before the crates reached Paris, Napoleon was in Poland preparing for the battle of Friedland in his headquarters at Finkenstein (present day Kamienec). As usual, the emperor was running all the affairs of state via correspondence, and it was on the 30 May that he sent a letter to Interior Minister Champagny detailing his conclusions concerning the architectural competition for the Madeleine in Paris. The Madeleine had been demolished and Napoleon intended to rebuild it as a temple 'in the Greek style' to the glory of the Grande Armée. About 100 drawings were sent to the commission judging the competition. Deciding on the winner (a certain Cl. Et. De Beaumont) the commission sent the propositions to Napoleon, imagining that he would rubber stamp their decision. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Napoleon wrote back that de Beaumont's project had been the first he had rejected. What he wanted, he continued, was a temple not a church, something dedicated to the glory of the Grande Armée. In this respect, Barthélémy Vignan, was the man who got it right. Amongst exceedingly detailed instructions as to the interior decorations, Napoleon also noted that the quadrige (chariot and horses from the Brandenburg gate) should be placed outside that temple.(4)

In Paris, work on the sculpture group was continuing a-pace but, as Denon noted in a letter of 12 September to the administrator of parks and gardens (in charge of the Orangery), M. Lelieur, repairs were still under way and he could in no way envisage moving the chariot in its present state – worse still the three months were up! The quadrige was finally moved to the Dépôt des Menus Plaisirs (Versailles) on 26 October, 1807, and in his letter to the architect, Fontaine, Denon stressed that no time should be lost in the refurbishment of the work. As for the cost, the grand total for repairs came to the sum of 21,370 Francs, an amount which Denon felt excessive, but he grudgingly admitted that the craftsman Cauler's careful work did in fact deserve it.(5)

With the chariot and horses now repaired all that was missing was a final resting place. Given the recent example of the triumphal arch in front of the Tuileries palace, the so-called Arc de Triomphe du Caroussel (which was sufficiently complete for the Garde impériale to pass beneath it on their victorious return from Eylau and Friedland), crowned with the horses from St Mark's in Venice, the Champs-Elysées Arc de Triomphe would have been an obvious site for the Berlin group. As we saw above, the emperor himself had suggested the Madeleine. Denon however had other ideas. He was later to remark in 1808 (but it had clearly been his opinion at the end of 1807), he felt that the statue group would be dwarfed by constructions on the scale of the Champs-Elysées Arc de Triomphe and the Madeleine. On 9 September, 1807, Denon suggested that the group could be placed on a fountain (actually a sort of horse trough) on the Pont-Neuf facing the Place Dauphine, today the site of a statute of Henri IV. This apparently meeting with disapproval, Denon proposed on 12 October, 1807, a pedestal and statue without fountain on the same site. Again the proposal would appear to have fallen upon deaf ears.(6)

After that, silence. The chariot and horses appear to have been forgotten in Versailles. The construction work on the Madeleine limped on until 1813 (still only the foundations were visible) when Napoleon downgraded the original plan of temple to the glory of the Grande Armée to a mere church, the fountain/statue on the Pont-Neuf was never built, and with the arrival of the Prussian soldiers on their entry into Paris in 1814, the statue group was seized by the Prussians and taken back to Berlin, where it was to become a symbol of national identity, freedom and victory.(7)