Stendhal or real life? If we are to believe Frédéric Masson, then the truth of the life-story of Pauline Fourès is indeed stranger than fiction. Born in southern France, 15 March, 1778, the daughter of clockmaker Henri-Jacques-Clément Bellisle and his wife Marguerite Barandon, Pauline worked initially as a milliner before coming to the attentions of Jean-Noël Fourès, a soldier on medical leave after being wounded in the campaigns of Year II and III in the Pyrenees.

They were married soon after, but right in the middle of their honeymoon, Jean-Noël was called up to go and fight in the Egyptian campaign. Not wanting to be parted, the young couple decided that Pauline would come too, dressed as Cavalry Chasseur. Managing to sneak on board the troop transport, La Lucette, Pauline remained undetected until their arrival fifty-four days later in Alexandria. Marched into the Damanhour desert, she was to receive her baptism of fire at the Battle of the Nile.

Pauline arrived in the capital Cairo with her husband on 30 July, 1798. Here she was able to dress once again as a woman, and her inexhaustible good humour kept up the spirits of the officer of the 22nd Chasseurs and the 7th Hussars. But contrary to what this description might imply, the marital life of the Fourès couple was renowned throughout the army as model, and Pauline is known to have thrown off the advances of a certain Lasalle, a new Brigadier in the 22nd Chasseurs.

But this is where Napoleon comes in. As Masson describes in his work, many of the soldiers on the expedition were looking forward to 'trying' the local women. Napoleon himself is recorded as being both highly dissatisfied with Josephine's reported infidelities and interested in the women of the region. However, when six local ladies were brought before the twenty-nine-year-old head of the army, he sent them away in disgust, repelled by their 'Rubens-esque' figures. He was to meet Pauline in the Tivoli Egyptien, a Cairo pleasure gardens run on the model of the Parisian Tivoli. Attracted by her blond hair, petite figure and perfect teeth, Napoleon sent Junot and Duroc to pay court for him. She however resisted. There then followed protestations, declarations, and expensive gifts – all calculated to soften the opposition. Then Napoleon played his master card. Fourès (who had been promoted to Lieutenant 18 October, 1798) was ordered to go to France on a mission to deliver a message to the Directory. He boarded Chasseur 28 December 1798.

Napoleon was then able to move in. The day after Fourès's departure, Napoleon asked Pauline (and other French women) to lunch. During the meal (at which Napoleon sat next to Pauline, paying every attention), a jug of water was (inadvertently?) spilt on Pauline's dress. Pauline was hurriedly taken into the commander-in-chief's private rooms to resolve the problem. As Masson delicately puts it 'Appearances were more or less kept up'. But only “more or less”. Napoleon's and Pauline's slightly extended absence caused the dinner guests to have certain doubts as to the real significance of the incident'.

But unfortunately Fourès came back earlier than expected. His vessel had been intercepted by the British ship Lion and had been sent back to Cairo. Fourès, furious on learning what had happened, treated Pauline extremely violently, at which Pauline demanded a divorce. This was granted and ratified by the war commissioner Sartelon. Following the divorce, Pauline re-adopted her maiden name Bellisle, hence her nickname 'La Bellilote'. Napoleon was deeply attached to Pauline and did not hide the fact that if she were to bear him a son he would divorce Josephine. In Cairo she lived a life of great luxury and excess. In his letters, Napoleon also called her his 'Clioupatre' and 'La Générale'.

When Bonparte left Egypt, 23 August, 1799, he gave command of both the army and Pauline (whom he was unable to take with him) to Kléber (she then became Kléber's mistress for several months). This lasted only a short time and she eventually returned to Paris, although she was never to see Bonaparte again. The First Consul did not however forget her. On 11 October, 1801, on advice from Duroc sent by Napoleon, she married a retired infantry officer, Pierre-Henri Ranchoup, a man of good family. Ranchoup was promoted to the consular government in Santander in Spain as a wedding present – again by the Consul's good offices. In 1810, Rachoup was sent to Sweden. Pauline, for whom the only thing in common with Ranchoup was her pleasure in acquisition, remained in Paris living the salon life.

Pauline was to live until 18 March, 1869. And in her later life, as in the early years, she never ceased to scandalise polite society. After being sent to the provinces during the Russian campaign on account of slightly too close friendships with some Russian aristocrats, she became the talk of the town because of her outrageous behaviour. For example, she would smoke while taking the air at the window, she read the Paris gazettes sitting outside the door of her solicitor, she frequented retired military circles and took her dog with her into church. Under the Restoration, in partnership with a retired captain of the Imperial guard, Jean-Auguste Bellard, she made several voyages to South America, where she sold furniture made in France and bought precious woods. In 1837, her fortune restored, she returned definitively to France (where Ranchoup had died in 1826).

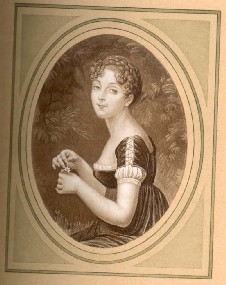

She was an accomplished woman, a passable painter, and she also wrote three novels. Her self-portrait is preserved in the French Bibliothèque Nationale under the title Madame de Ranchoup. Her novels are Lord Wenworth (1813), Aloïze de Mespres. Nouvelle tirée des chroniques du XIIeme siècle (1814), and Une chatelaine du XIIeme siècle, nouvelle (1834). She was an enthusiastic art collector and left in her will several paintings to the city of Blois.

Bibliography

Dictionnaire de biographie française, vol. 14 (Flessard-Gachon), Éditions Letourney et Ané, 1979, under 'Fourès (Jean-Noël)', coll. 763-65

Dictionnaire Napoléon, (ed. Jean Tulard), Fayard 1989, under 'Fourès', p. 753

Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, June 1977, no. 315, pp. 542-48

Beauchamp, C. 'La première maitresse de Bonparte', Bulletin de la société historique des VIIIeme et XVIIeme arrondissements, 1931-1932

Masson, F., Napoléon et les femmes, Ollendorf, Paris, 1894

Régis, R., Pauline Fourès, dite “Bellilote”, maitresse de Bonaparte en Égypte, Éditions de Paris, 1946.