-

Introduction

At about 9 pm on the 18 June 1815, two British and Prussian generals, the Duke of Wellington and Field Marshall Blücher, met at a farm just south of Waterloo called La Belle Alliance. They had just beaten Napoleon I in battle, and Blücher was keen to call the battle ‘Die Schlacht von Belle-Alliance’, in honour of the co-operation between the British and Prussians. Wellington, however, named it after his headquarters at Waterloo.

Quite how had this extraordinary encounter in southern Belgium involving Prussia and Britain come about? It was largely to do with Prussia’s relations with France during the first decade of the nineteenth century. The twin battles of Jena and Auerstaedt in October 1806 had marked the end of Prussian independence. France was to play a significant role in the organisation and despoliation of these northern German-speaking lands. Out of this virtual collapse of the Prussian state, Blücher and Gneisenau were to emerge as the prominent military leaders. However, things were to change for Prussia when Napoleon invaded Russia in June–July 1812, ostensibly to force Tsar Alexander I to adhere to the Continental Blockade. The two-year war which ensued culminated in a monumental three-day battle in Leipzig in 1813 involving half a million combatants (the Battle of the Nations or Völkerschlacht) and the multiple combats in the Marne valley (France) in 1814, known as the French campaign. During this time, Prussia, buoyed up by British funds, supported the Russians and Austrians in driving Napoleon back to France. Napoleon was forced to abdicate, and the ensuing international congress at Vienna in the autumn of 1814 set about reorganising Europe, whilst the Peace of Paris and Treaty of Fontainebleau had granted Napoleon sovereignty over the tiny kingdom of Elba. At Vienna, where Prussia was represented by King Friedrich Wilhelm III, Karl Friedrich von Hardenberg and Wilhelm von Humboldt, the Congress was gradually drawing to a close in the spring of 1815, the extraordinary news arrived that Napoleon had landed in France…

Origine de l’étouffoir impérial [‘Origins of the Imperial Snuffer’], caricature by Lacroix, 1815, showing Blücher and Wellington stuffing Napoleon in the bin. Arenenberg, Napoleonmuseum. © Fondation Napoléon

-

Documents

Documents

This is a collection of primary sources directly relating to the Prussians’ campaign and victory along with the British at Belle Alliance/Waterloo, including battle reports, newpaper articles and contemporary evaluations of the Prussian army.

Poem in honour of Blücher

from the title page of Gebhard Lebrecht v. Blücher, preußischer Feldmarschall und Fürst von Wahlstatt nach Leben, Reden und Thaten geschildert (Stuttgart: J. Scheible, 1835).

Marschall Vorwärts, Fürst von Wahlstatt,

Gebhard Lebrecht Blücher heißt er;

Ja, Marsch! Alle vorwärts reißt er:

Hart kann euch der Gebhard geben,

Lebrecht heißt der Wahlstattmeister,

Denn er lebt das rechte Leben.Rough translation: Marshall Forwards, Prince of Wahlstadt,

Gebhard Lebrecht Blücher is his name!

Yes, march! Wrenching each man forwards!

He’ll fight it hard,

Lebrecht is his name,

For he lives the upright life.**The poem explains why Blücher is nicknamed ‘Vorwärts’, and puns on his names ‘Gebhard’ (containing ‘geben’, to give, and ‘hart’, hard) and ‘Lebrecht’ (‘recht’, upright, righteous, and ‘leben’, to live).

Fortescue’s comments on the Prussian army

Sir John Fortescue wrote this complete, 20-volume history of the British army between 1899 and 1930. This extract is from J. W. Fortescue, vol. X, 1814-1815, Ch. 12, pp. 248-49.

Sir John Fortescue wrote this complete, 20-volume history of the British army between 1899 and 1930. This extract is from J. W. Fortescue, vol. X, 1814-1815, Ch. 12, pp. 248-49.

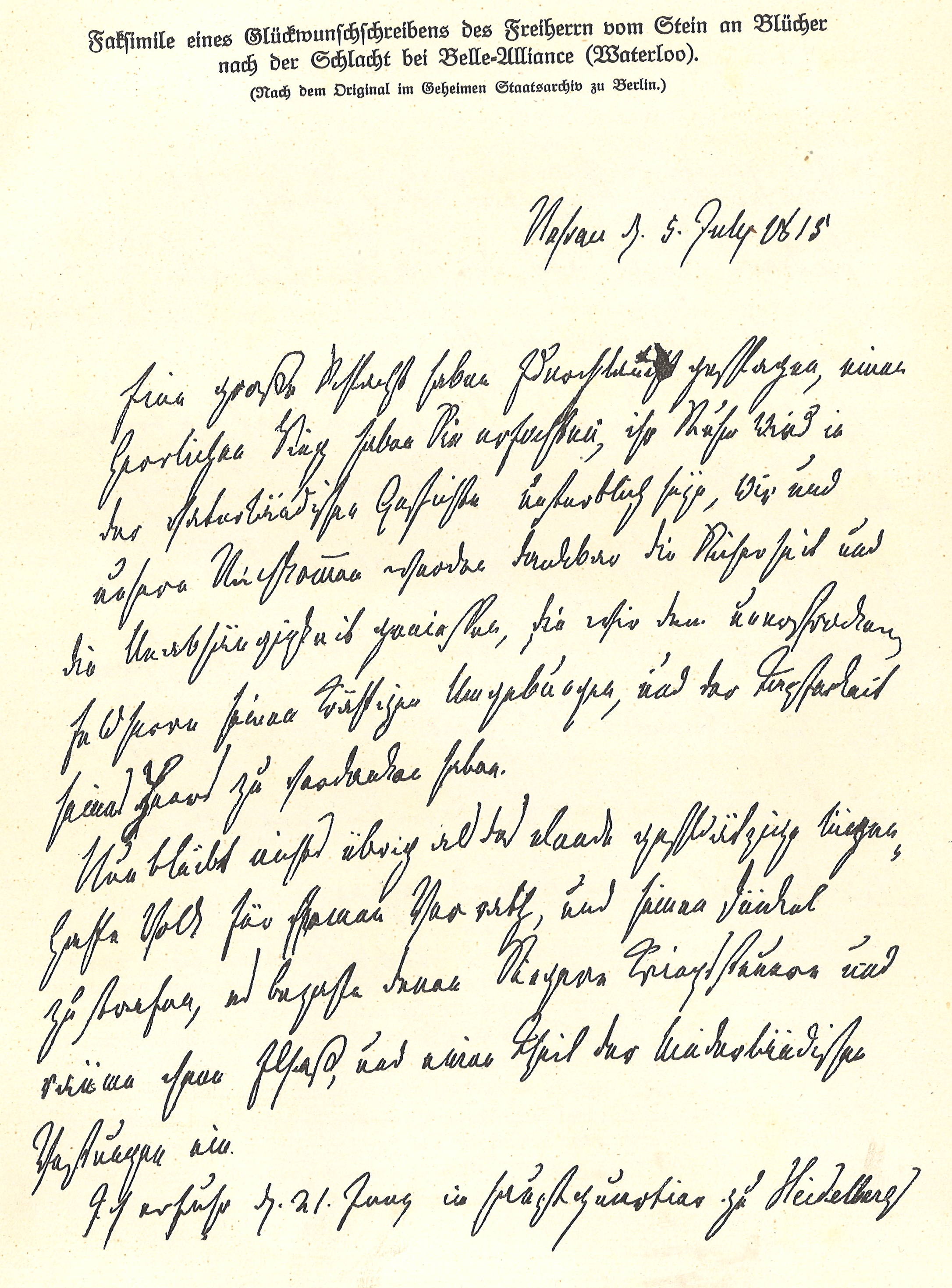

Congratulatory letter from the statesman Karl von Stein to Blücher upon his 1815 victory

The picture shows the first page of the letter. The full document reads as follows:

The picture shows the first page of the letter. The full document reads as follows:Naßau, d. 5. July 1815

Eine große Schlacht haben E. Durchlaucht geschlagen, einen herrlichen Sieg haben Sie erfochten; Ihr Ruhm wird in der Vaterländischen Geschichte unsterblich seyn, wir und unsere Nachkommen werden dankbar die Sicherheit und die Unabhängigkeit genießen, die wir dem unerschrockenen Feldherrn seinen kräftigen Umgebungen, und der Tapferkeit seines Heers zu verdanken haben.

Nun bleibt nichts übrig als das elende geschwätzige lügenhafte Volk für seinen Verrath, und seinen Dünkel zu strafen, es bezahle denen Siegern Kriegsteuern und räume ihnen Elsaß und einen Theil der Niederländischen Festungen ein.

Ich erfuhr d. 21 Juny im Hauptquartier zu Heidelberg diesen herrlichen Sieg und war Zeuge des Eindrucks den er auf den Kayser und alle seine Umgebungen machte.

Ich bleibe sechs Wochen hier um das Bad zu brauchen und werde alsdann das Hauptquartier, und auch E. Durchlaucht aussuchen, wo wir das weitere ueber die Zukunft verabreden können. – Gott erhalte unseren edlen sieggekrönten Feldherrn, das ist der Wunsch jedes braven Deutschen, und besonders derer die sich unter die Zahl seiner Freunde rechnen.

K. F. von Stein

Source: J. v. Pflugk-Harttung, 1813-1815: Illustrierte Geschichte der Befreiungskriege (Stuttgart: Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft 1913)

Translation:

Your Excellency has fought a great battle and won a splendid victory; your fame will be eternal in the history of the Fatherland. We and our descendents will enjoy the great safety and independence we owe to the fearless soldier and his mighty entourage, and to the bravery of his army.

There is now nothing to be done but to punish that miserable, blithering, lying nation for its betrayal, and to punish its arrogance… They should pay war taxes to their victors and grant them Alsace and part of the Dutch fortresses.

I learned of this victory on 21 June at the headquarters in Heidelberg and was witness to the reaction of the Emperor and his entourage.I will remain here for six weeks to avail of the baths and will then join the headquarters and your Excellency, where we can make plans for the future. – May God sustain our noble, victorious General: that is the wish of every good German, especially of those who count themselves his friends.

-

Timeline

7 – 10 March 1815

News of Napoleon’s departure from Elba and arrival on the French coast reaches the European allies at the Congress of Vienna. Napoleon is declared an outlaw. The Allies see Napoleon as a threat to France (recently restored to the Bourbon monarchy) and, thereby, to Europe.The Prussian General Kleist von Nollendorf gathers his much-diminished troops of around 20,000 men at Juliers (Jülich/Gulik, now in Germany on the Belgian border) and makes plans to rally the Westphalian and Belgian militia. Meanwhile, the Dutch Prince of Orange, under the eye of the British general Sir Hudson Lowe, gathers the English troops at Ath, occupying Mons and Tournay. These troops (a small band of British and Hanoverians) had remained there as border guards since the liberation of the Netherlands in 1814. Nollendorf and the Prince of Orange agree to join forces if Napoleon attacks Tirlemont (Tienen), a Belgian town fifty kilometres due east of Brussels almost equidistant between the two positions. Kleist’s corps would eventually number 26,200 men, divided into 30 battalions, 12 squadrons, and two and a half batteries, but it was to remain stationed on the Moselle right until 16 June.

11 March 1815

Back in Vienna, King Friedrich Wilhelm III orders the reinforcement of Prussian troops along the Rhine, especially at Coblenz, Cologne and Wesel. The next few days (including a cabinet order dated 18 March which created four new corps mostly stationed in German-speaking lands) would see a council of war and the official mobilisation of the Prussian troops. Blücher is appointed Commander of the newly-christened Field Army of the Lower Rhine. This army included former French soldiers in the newly-formed Prussian states. There would be much discussion, both at the time and later, as to the relative loyalties of these ‘swapped’ citizens.30 March 1815

The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Corps cross into Belgium. The first two corps were composed of one-third militia, the 3rd Corps of a half, and the 4th (reserve) Corps had as many as two-thirds inexperienced militia.5 April 1815

Wellington arrives in Brussels from Vienna, having visited Blücher’s chief of staff, Gneisenau, at the Prussian headquarters in Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle), right on the Belgian border. In the following week, despite the minor scandal provoked by Napoleon’s publishing of a former secret treaty between Britain, Austria and Royalist France against Russia and Prussia in an attempt to disrupt the British-Prussian military negotiations, Gneisenau and Wellington come to an agreement on invading France and work out respective army positions. They both aim to enter France from Belgium and close in on Paris.10 April 1815

Blücher leaves Berlin and travels through Magdeburg, Cassel, Cologne, Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) to Liège (fifty kilometres west of Aachen), arriving on 19 April. There, he joins his headquarters and three battalions of Saxon troops whom the Congress of Vienna had recently reallocated to them. These Saxons had however been very supportive of Napoleonic Europe. At this stage, Blücher expects war to be over soon. In his rather idiosyncratic spelling, he wrote to his wife on 24 April that ‘ich glaube daß wir den krig wenn er beginnt ballde beendigen werden’ [sic] (‘If the war begins, it will be a short one’).25 April 1815

Following the Prussian King Frederick William’s orders of mobilisation, Blücher sends out a memo for the administrative restructuring of the Prussian army and to divide it into four corps.2 – 6 May 1815

Some soldiers in the problematic Saxon troops (mentioned above) rebel, throwing stones at Blücher’s window and refusing to obey him. Seven Saxons are court-martialled and shot, and the rebels are brought under control. Part of the Saxon battalion and the infantry is sent to Aachen. The King of Saxony asks Wellington to take his troops under his command.3 May 1815

Wellington and Blücher meet at the mid-point of Tirlemont, agreeing to support each other if Napoleon attacks the English or Prussian armies. Rumours of Napoleon’s advance had brought about the meeting. They agree to concentrate 220,000 English, Prussian, Belgian, Hanoverian and Brunswick troops between Liège and Courtrai, along the Quatre-Bras/Sombreffe line. Both are still waiting for the Russian and Austrian armies to arrive at the Rhine and are expecting the English and Prussian armies to form the outposts of the allied armies.11 May 1815

Blücher fixes his headquarters at Hannut, 20 miles west of Liège, slightly closer to the British troops.27 May 1815

The Prussian army gathers mostly along the Meuse river (but with some forward positions reaching as far south as Rochefort and Dinant), with the 1st Corps centred around Charleroi, the 2nd around Namur, the 3rd around in–between Ciney and Huy, and the 4th at Liège. Altogether they number 115,000 soldiers. The formation is supposed to leave the French unable to predict whether the Prussians will join up with Wellington and the British armies on the right or the approaching Russian armies on the left. At this stage, Blücher is hoping to avoid hostilities until the Russians and Austrians arrive, expected around 1 July.28 May – 2 June 1815

Wellington and Blücher meet together in Hasselt (Netherlands). According to Wellington’s despatches, Blücher is impatient to begin the campaign, but the latter wishes to wait for the Austrian Prince Schwarzenberg’s Army of the Upper Rhine.13 June 1815

Napoleon and his army are approaching the French-Belgian border, but reports are extremely contradictory as to whether he is planning an attack on the Prussians or the English, so both Blücher and Wellington stay put.15 June 1815

Napoleon’s approach comes as something of a surprise to Blücher, who is by now in Namur (Belgium). Wellington and he had planned their offensive for 27 June. Blücher thus takes up his headquarters in Sombreffe and immediately gives orders for his army corps to concentrate. Having received the news that only part of the 4th Corps is at Hannut (in Liège), he gives the order for them to come to Sombreffe via Gembloux.16 June 1815

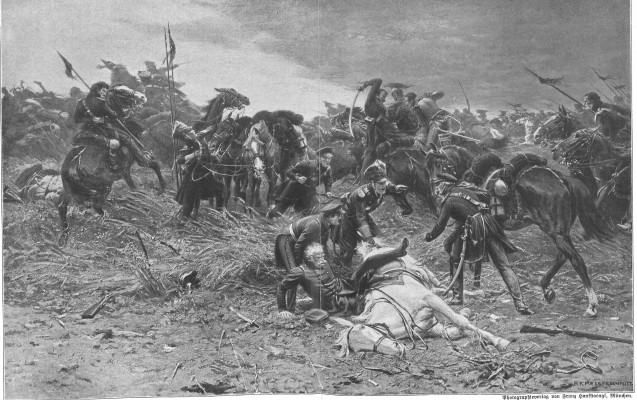

Wellington and Blücher meet at the windmill of Bussy at 1 pm, where they agree that Napoleon seems to be about to attack Ligny, not Quatre-bras. The Prussians take responsibility for this battle, but the 4th corps, headed by General von Bülow, doesn’t arrive in time, and the 80,000-strong Prussian army loses the Battle of Ligny against Napoleon. Blücher is injured in the attack when his horse is shot from underneath him.Later that same afternoon, the French Marshal Ney leads an attack at Quatre-Bras against the British, but the latter’s superior numbers and French indecision allow them to avoid defeat.

17 – 18 June 1815

Though badly mauled on 16 June, Blücher retreats not east towards Prussia but re-establishes his position around Wavre (north and east from Ligny), thereby staying in contact with the allied force which had retreated from Quatre-Bras to Waterloo.One of Wellington’s ADCs reaches Blücher at 11 pm on 17 June, informing the Prussian general that the British general would fight a defensive battle at Waterloo. Blücher, after consultation with Gneisenau, resolves to send Bülow’s 4th corps to attack the enemy’s right flank. This would be followed by the 2nd corps, with the 1st and 3rd held in reserve. The 4th, 2nd and 1st corps march in two columns from Wavre towards the battlefield at Waterloo. Whilst Blücher was to hold the French off at Wavre, Bülow and Pirch II were to lead the left column (that which would finally take Plancenoit, to the rear of Napoleon’s right) and Zieten on the right column would finally emerge onto the battlefield alongside Wellington’s left round about 7 pm.

Though the battle at Plancenoit was to be hard fought, the Prussians eventually overrun the French right, causing the French army to turn and flee. Blücher was famously to meet Wellington on the battlefield between 9 and 10 pm, close to the Belle-Alliance farm, where the Prussian general used the only French he knew: ‘Quelle affaire !’ are the words that history has recorded.

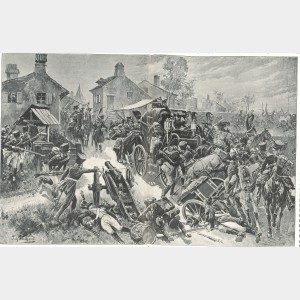

Given the battering the Allied army had received throughout the day, the relatively fresh Prussian troops were to take the lead in pursuing the fleeing French troops. The Prussians had neverthless lost 7,000 men. Napoleon’s carriage was to be seized by Prussian cavalry at Gemappes, and the routed French were to be given no quarter by the furious Prussian pursuit. Blücher’s advance guard was finally to reach the outskirts of Paris on 29 June. With Napoleon’s abdication on 22 June, the war would officially end upon the signature of the Convention of St-Cloud on 3 July 1815.

Ironically, and almost as a historical footnote, the Prussian general, Thielemann, left to hold position at Wavre, was to be beaten at Wavre by Grouchy on the day after Waterloo. Despite this useless victory, Grouchy’s failure to return to the battlefield at Waterloo was to be generally held as as the real reason that Napoleon lost on that fateful 18 June 1815.

-

Biographies

Field Marshal Gebhard Lebrecht Blücher, General of the Prussian Forces

August Wilhelm Gneisenau, Chief of General Staff

Karl von Grolman, Quarter-Master General

Hans Ernst von Zieten, Commander of the 1st Corps

Georg von Pirch (von Pirch I), Commander of the 2nd Corps

Johann Adolf von Thielemann, Commander of the 3rd Corps

Friedrich Wilhelm Bülow von Dennewitz, Commander of the 4th (Reserve) Corps

The Prussian army pursue the French after Waterloo, capturing Napoleon’s carriage, bicorn hat and sword. Reproduction of a painting by Fritz Neumann in Pflugk-Harttung, Illustrierte Geschichte, pp. 406-7.

The Prussian army pursue the French after Waterloo, capturing Napoleon’s carriage, bicorn hat and sword. Reproduction of a painting by Fritz Neumann in Pflugk-Harttung, Illustrierte Geschichte, pp. 406-7.

Blücher and the Waterloo campaign

The Prussian army’s role in the Battle of Waterloo (or the Battle of Belle-Alliance, as they named it) has often been underestimated. This dossier offers a close-up on the German cultural hero Blücher and the composition and whereabouts of his troops between March and June 1815.

The images of this medallion are from the fly-leaf of Captain William Siborne’s History of the War in France and Belgium, in 1815, Vol 2, 2nd edition (London: T. and W. Boone, 1844). The engraving reads ‘Dem Fürsten Blücher von Wahlstatt die Bürger Berlins im Jahr 1816’ (the people of Berlin honour Prince Blücher von Wahlstatt, 1816), and Blücher’s nickname ‘Vorwärts’ accompanies the horseback engraving.

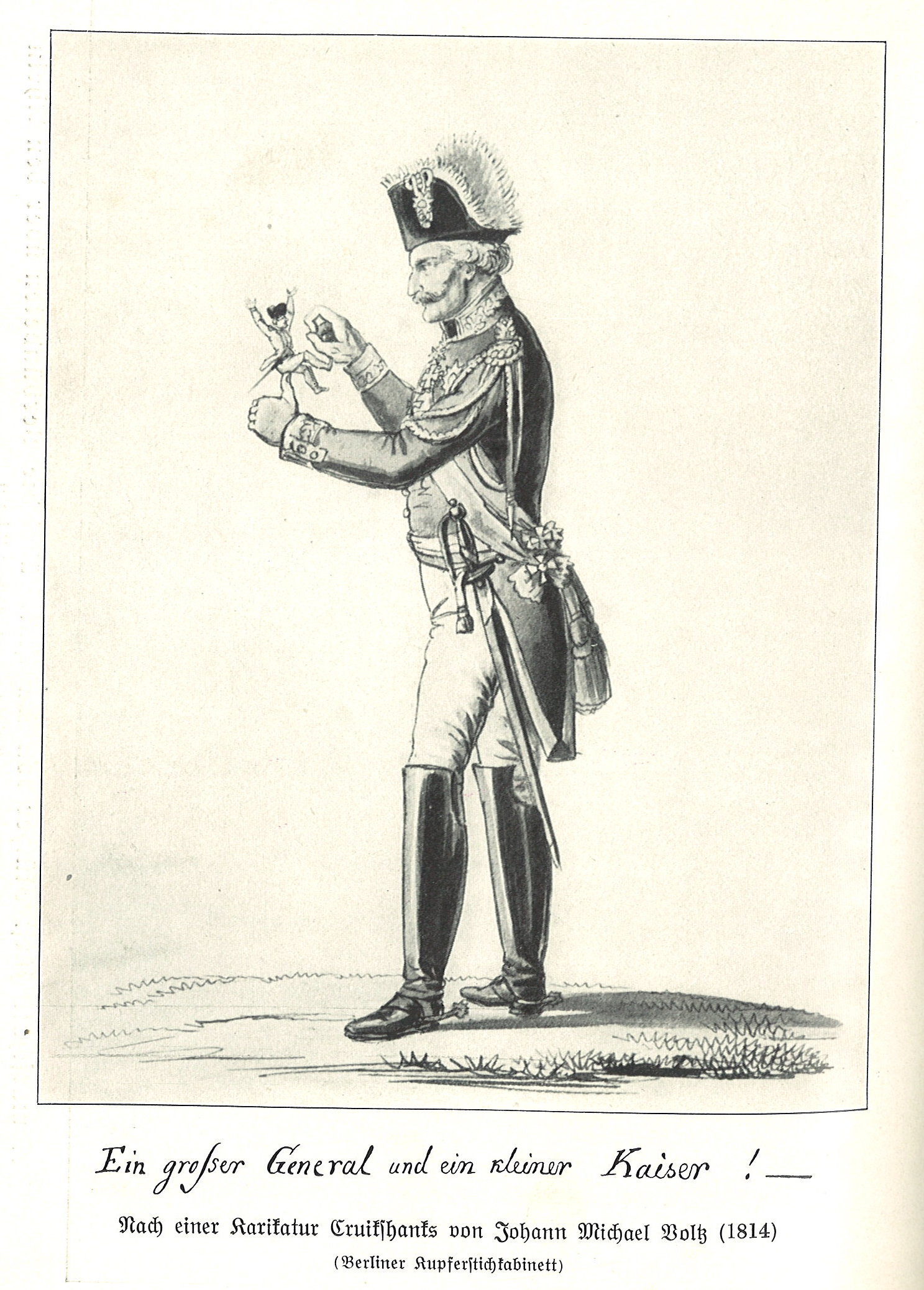

The images of this medallion are from the fly-leaf of Captain William Siborne’s History of the War in France and Belgium, in 1815, Vol 2, 2nd edition (London: T. and W. Boone, 1844). The engraving reads ‘Dem Fürsten Blücher von Wahlstatt die Bürger Berlins im Jahr 1816’ (the people of Berlin honour Prince Blücher von Wahlstatt, 1816), and Blücher’s nickname ‘Vorwärts’ accompanies the horseback engraving. ‘A Great General and a Little Emperor’, an 1814 caricature by Johann Michael Voltz based on Cruickshank’s cartoons. This image precedes the June 1815 campaigns, and is referring to Blücher’s involvement in the campaign for France, driving Napoleon back to Paris from Russia. In: Friedrich Schulze, 1813 – 1815: Die deutschen Befreiungskriege in zeitgenössischer Schilderung (Leipzig: R. Voigtländer 1912). Another version of the same caricature, accompanied by a satirical poem, is available on the

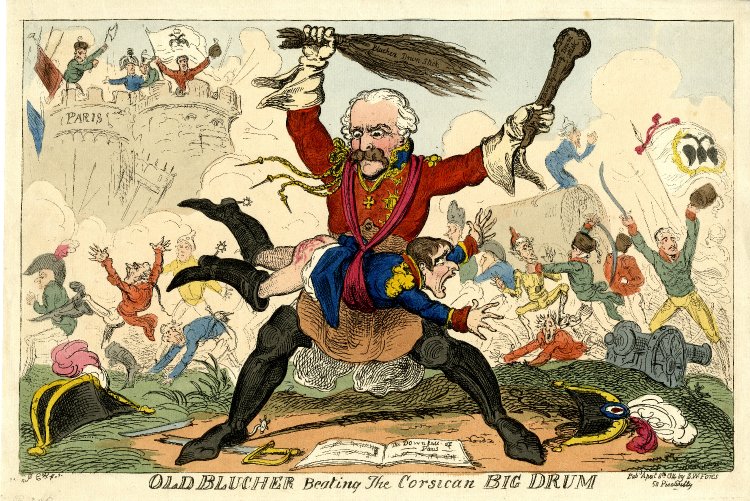

‘A Great General and a Little Emperor’, an 1814 caricature by Johann Michael Voltz based on Cruickshank’s cartoons. This image precedes the June 1815 campaigns, and is referring to Blücher’s involvement in the campaign for France, driving Napoleon back to Paris from Russia. In: Friedrich Schulze, 1813 – 1815: Die deutschen Befreiungskriege in zeitgenössischer Schilderung (Leipzig: R. Voigtländer 1912). Another version of the same caricature, accompanied by a satirical poem, is available on the  Like the print above, this caricature by Cruickshank also refers to Blücher’s victories against Napoleon in the 1813-14 campaigns for Germany and France and to the Prussian entry into Paris on 31 March 1814. The French army are shown fleeing for their lives, and, as above, Napoleon is depicted as a tiny, flailing weakling. The proclamation under the two commanders reads ‘Downfall of Paris’.

Like the print above, this caricature by Cruickshank also refers to Blücher’s victories against Napoleon in the 1813-14 campaigns for Germany and France and to the Prussian entry into Paris on 31 March 1814. The French army are shown fleeing for their lives, and, as above, Napoleon is depicted as a tiny, flailing weakling. The proclamation under the two commanders reads ‘Downfall of Paris’.