-

Introduction

The Duchy of Warsaw was created by Napoleon in July 1807 and was seen by the Poles as a sign of a future restoration of their nation. This, however, was not to be, as the Duchy ceased to be with the fall of the French Empire. Its fate was decided at the Congress of Vienna; the Polish land was once more split between Austria, Prussia and Russia.

-

Documents

-

Timeline

Introduction

By the mid-18th century, Poland (know as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) was no longer the strong European power it had been in the 17th century. The election of its kings, once decided by the Polish nobles, now took place under the influence of neighbouring powers, particularly Russia. In 1764, as a result of pressure from the Tsarina Catherine II, Stanislas-Augustus Poniatowski was elected king of Poland. At the time, however, he was held to be a weak king, and Poland effectively became a Russian vassal state. In international terms, the territory was no longer master of its own destiny. The philosophy at the time governing European interstate relations was known as the ‘balance of power’. Were one European power to be perceived to have gained in influence (whether by political, financial or territorial gain) with respect to the other countries within the system, it was accepted that those other countries could demand reparation. In this context, the growth of Russia’s power in the course of the Russo-Turkish wars (1768-1774) destabilised international relations, notably for Prussia and Austria. With France and Britain taking a backseat, the two German powers were forced to consider their options should they be forced into the conflict with Russia or what compensation they should receive in return for Russia’s aggrandizement. Russian victories on the Black Sea and the Balkans applied further pressure on Austria and Prussia. Their alliances with Russia, which had been engineered for the earlier conflict, the Seven Years War, no longer served their interests. Austria was not only politically but also strategically threatened and, worse still, could have been forced to join the Turks in a potentially catastrophic war against Russia. Prussia too was faced with having to honour an alliance with Russia which could draw it into a war with Austria. Though militarily stronger than Russia when united, the two German powers were not sure of winning such a campaign, which would certainly be long and draining. Simultaneously, within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a civil war driven by Polish nationalists calling themselves the Confederation of Bar destabilised the state, itself already weak as a result of political gerrymandering by Polish nobles, which rendered any national action on the part of the Poles impossible. Frederick the Great of Prussia therefore suggested that the three powers (Russia, Prussia and Austria) nibble off parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to the south, east and west, to allay fears of an eastern European military conflagration.

THE GRADUAL DISAPPEARANCE OF POLAND

1772: First partition of Poland. Agreements (one signed in St Petersburg on 6 February and the other in Vienna on 19 February) consigned Polish territory to Russia, Prussia and Austria. In early August of the same year, troops from the respective countries entered Commonwealth land to take possession of their new lands.

1773: Under constraint, Poles voted to accept the de facto occupation. Once the three powers had occupied their new territory, they had demanded that the Polish king and parliament sign a treaty to approve these territorial changes. King Stanislas-Augustus Poniatowski put this vote off for as long as possible. In the end, under Russian duress and bribery, less than half of the regular number of representatives eventually turned up to vote on 18 September.

7 October, 1788 – 29 May, 1792: A Polish-Lithuanian parliament was held in Warsaw (known as the Four-Year Sejm or the Great Sejm or Parliament) as a reaction to this first partition of Poland. After enacting many social and economic reforms which included the strengthening of executive power, the Sejm became swamped by the Patriot Party in 1790, which was led by Ignacy Potocki, a Polish noble who was against the Russian control and Poniatowski’s reign. On 29 March, 1790, after several months of negotiations, Potocki led his party into an alliance with Prussia. This action, coupled with an easing of relations between the king and Potocki and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy enshrined in a constitution, adopted on 3 May, 1791, made the country more autonomous and more likely to attempt to escape from the Russian stranglehold. Catherine II, however, did not react immediately, preferring to see the result of the war in Belgium pitting Prussia and Austria against the fledgling French republic.

1792: The defeat of the Austrian/Prussian coalition against France at Valmy on 20 September and the collapse of Austrian plans to render Polish lands ‘a secure, peaceful Puissance intermédiaire et de convenance under all its immediate neighbours’ allowed Catherine (strongly encouraged by her recent appropriation of the Crimean region) to take independent action and bring Poland back into line.

1792-1793: A group of Polish nobles collaborated with Russians at St Petersburg and asked Catherine to restore Polish liberties (in effect, to remove the new constitution). The resulting Targowica Confederation (created on 27 April, 1792) led to the entry of 100,000 Russian soldiers into Polish lands in May of the same year. Despite resistance and initial success, Russian superior manpower put down any opposition to the confederation and the result was the Second Partition of Poland. With further Polish territory being split between Russia and Prussia, both powers installed troops in large swathes of Polish territory to the east and west, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was now merely a narrow stretch of land running North-South from the Baltic to Austrian Galicia. The Treaty of St Petersburg, a document enshrining the Second Partition, was signed on 23 January, 1793 in the eponymous Russian city. One of the consequences of the Second Partition was the reduction of the Polish army to about 36,000 men, an action which angered many Polish commanders such as Tadeusz Kosciuszko and Prince Josef Poniatowski (King Stanislas-Augustus’ nephew).24 March, 1794: Following the events in France which had led to the fall of Robespierre and due to Russian and Prussian repression in Poland, Tadeusz Kosciuszko led an insurrection (in fact, a mixed bag of regular troops and enrolled peasants) in an attempt to free Poland from Russian and Prussian control. Russia, Prussia and Austria joined together to fight the uprising, and due to their far superior numbers defeated the opposition, ending the insurrection on 16 November of the same year. The victorious powers divided what remained of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between themselves and, as a result, Poland ceased to exist. This Third Partition of Poland was formalised in a treaty signed on 24 October, 1795. Soon after this, Stanislas-Augustus Poniatowski, the last king of Poland, was forced to abdicate, and he sought refuge in Russia, where he lived until his death in 1798.

POLISH EXILES SEEK SUPPORT FROM FRANCE

1795: After the disappearance of Poland, organizations sprang up in Paris claiming to be the Polish government-in-exile, namely the Deputation (Deputacja) of Franciszek Ksawery Dmochowski and the Agency (Agencja) of Józef Wybicki. Many Polish exiles (soldiers, officers and volunteers) emigrated, notably to Italy and to France. Given French Revolutionary refusal to allow foreign troops to serve in France, these exile volunteers were detailed to fight in Italy by the Deputation and the Agency.

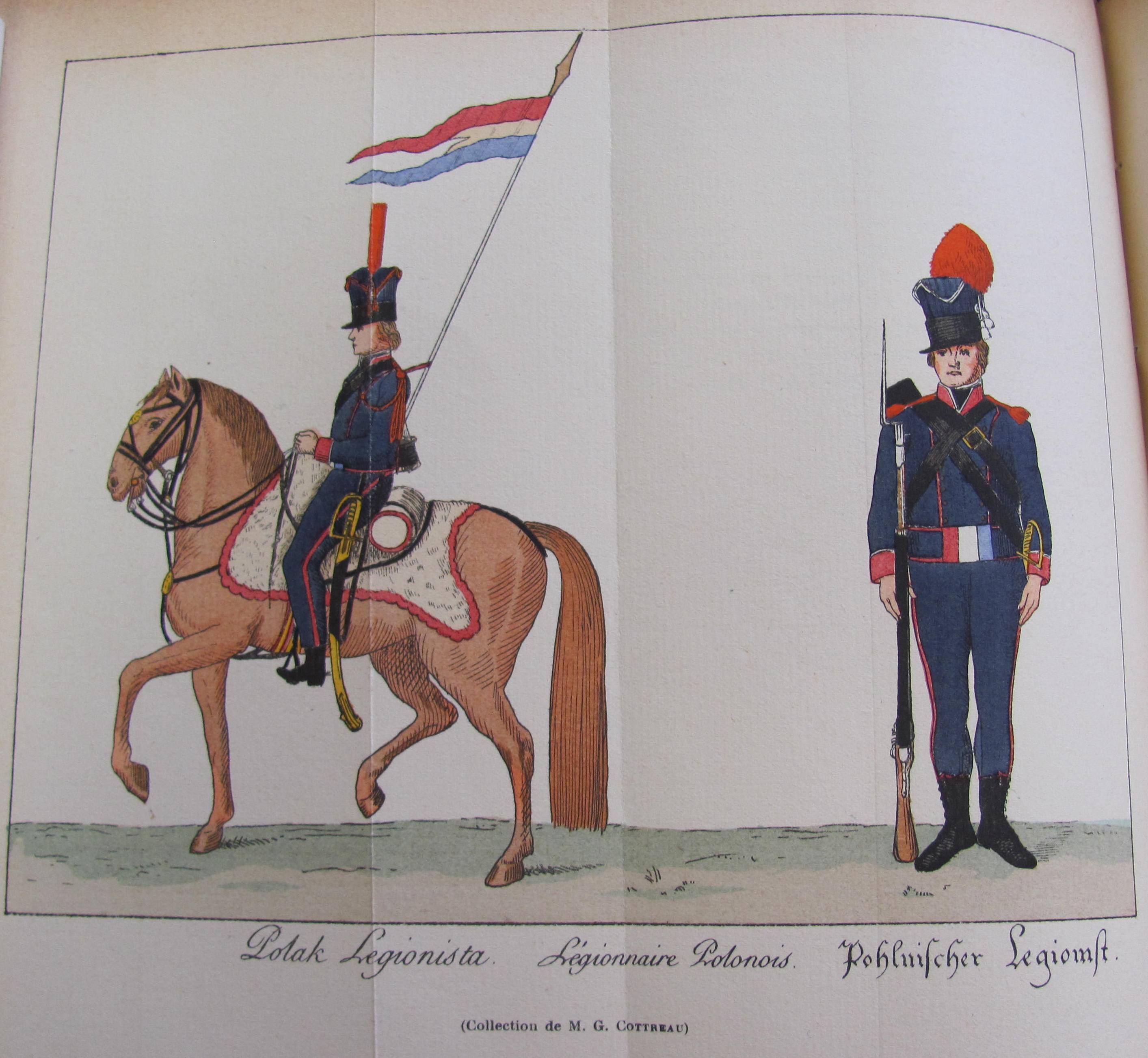

1795: After the disappearance of Poland, organizations sprang up in Paris claiming to be the Polish government-in-exile, namely the Deputation (Deputacja) of Franciszek Ksawery Dmochowski and the Agency (Agencja) of Józef Wybicki. Many Polish exiles (soldiers, officers and volunteers) emigrated, notably to Italy and to France. Given French Revolutionary refusal to allow foreign troops to serve in France, these exile volunteers were detailed to fight in Italy by the Deputation and the Agency.January, 1797: After negotiations in Milan with Napoleon, General Jan Henryk Dombrowski – who had played an active role in the Kosciuszko uprising of 1794 – was allowed to form a Polish legion, made up of Polish emigrants, prisoners or deserters from the Austrian army. In a four-point plan, sent to the Directory and dated 10 October, 1796 (document published in the article by Léonard Chodzko “Des Légions Polonaises en Italie”, Revue des Deux Mondes t.1, 1829), Dombrowski had laid out his scheme for Polish renaissance as follows:

“1 – The legions will serve as the nucleus for the building of an army for Poland;

2 – These legions will be composed of certain general officers who have served with distinction in the two recent campaigns in Poland against Russia and her allies;

3 – The corps of these legions will be made up of subaltern officers re-formed in Poland who, by patriotism, have nearly all refused the offices which the government of co-invading powers have offered them, and by Gallicians forcibly enrolled in the Austrian army;

4 – The legions will serve as volunteers in the armies of the French Republic, and they will be subordinate to the Republican generals and will go to wherever the French government will send them, should these negotiations come to fruition”.On 9 January, 1797, Dombrowski signed an agreement (countersigned by Napoleon) with the Repubblica Transpadana (the sister republic created out of Austrian Lombardy) formalising the creation of two Polish Legions attached the Italian republic, the First and Second Polish Legions. On 20 January, Dombrowski wrote an article in the Corriere Milanese, an Italian Newspaper, calling upon Poles to enlist – by the end of 1798 his legions numbered 10,000 men.

VAIN POLISH MILITARY SACRIFICE FOR FRANCE

1799: The Polish Legions were to suffer great losses in Italy and Switzerland during this year whilst the French troops were away fighting in Egypt. The First Polish Legion fought and lost many men at the battles of Trebbia, Novi and the Second Battle of Zurich. The Second Polish Legion was to cease to exist after the siege of Mantua and the subsequent capitulation of the town by the French (April-July, 1799). The commander of the fort, François-Philippe de Foissac-Latour, agreed that the Austrians could have the Polish deserters as part of his surrender terms. Only a small number of Poles managed to escape capture and subsequent reintegration into the Austrian army.

16 October, 1799: Bonaparte returned to Paris from Egypt. After his participation in the bloodless coup d’état of 18-19 Brumaire, he was proclaimed First Consul on 10 November. On 10 February, 1800, following the recent defeat in the Cisalpine Republic, an “arrêté des consuls” joined the two Polish legions (namely Dombrowki’s legions of 1797 and the ‘Legion du Danube’ created on 8 September 1799 under General Kniaziewicz in Strasburg) in a single body in Marseilles, the ‘Légion Polonaise d’Italie’ (later the 1ère Légion Polonaise) and the ‘Légion Polonaise du Danube’ (later 2de Légion Polonaise). These consisted of Polish deserters and prisoners and entered into action from 30 April, 1800. Elements of the Danube legion would be decisive for the outcome of the battle of Hohenlinden, 3 December, 1800. These legions were to be reorganised into 3 demi-brigades, the first in Modena on 11 December 1801, and the second in Reggio Emilia the following day and the third in Livorno ten days later. On the creation of the Repubblica Italica, the three demi-brigades were attached to the new republic, the latter two also suffering further reorganisation to become the 114th (1803) and 113rd (2 September, 1802) demi-brigades.

9 February, 1801: The peace Treaty of Lunéville was signed between the French Republic and the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. The Polish soldiers who had participated in the previous campaigns were disappointed that no mention had been made of Poland in the treaty. They had hoped that Napoleon would recognise their participation in his campaigns and help them restore their country.

August and September, 1802: Despite the resignation of many Polish legionnaires (such as General Kniaziewicz) who felt they would never regain their country by serving the French, some Polish soldiers continued to fight for France, and those in the 113rd were to be sent out as the last part of the second wave of the (significantly international) expedition force to Saint-Domingue. Though initially successful, the French forces were forced to flee the island in December 1803 after losing tens of thousands of men (mostly to yellow fever). Some sources indicate that of the six thousand Polish soldiers who went out, only about three hundred returned in 1804.

1805: After the battle of Austerlitz, Polish troops in Italy were renamed 1st Polish Legion (1ère Légion Polonaise) and attached to the newly-created Kingdom of Italy. They fought well against the Austrians at Castel Franco (24 November). However, the following year, in the Maida campaign (3 July, 1806), the demi-brigade in the service of the Kingdom of Naples (all that was left of the original Polish Legions led by Dombrowski and Kniaziewicz) suffered a severe defeat, with many taken prisoner. As for other Polish soldiers, after long inactivity “pending re-organisation”, they were gradually integrated into French service throughout the years 1805 and 1806.

NAPOLEONIC VICTORIES AGAINST AUSTRIA AND PRUSSIA IGNITE POLISH HOPES

14 October, 1806: The French victories at Jena and Auerstaedt marked the end of an independent Prussia. This had important repercussions for Poland. Imperial troops marched triumphantly into Berlin on 27 October. A ‘Legion of the North’ had been created (although this legion included Poles, it had been deliberately designed to be more than uniquely Polish), and units of this legion had fought with the Grande Armée at these twin battles. In November, Dombrowski’s four-point plan of nine years earlier finally began to come to fruition as Polish troops under him were to enter former Polish territories near the city of Poznan, and this was to result in an influx of recruits for the legion.

14 January, 1807: A provisional governmental commission was created by Napoleon in Warsaw, made up of seven members of the aristocracy, including Stanislas Malachowski as its president. Besides from this commission, five ministers (War, Interior, Finance, Police and Justice) were appointed. Their main aim was to create a national army to strengthen Napoleon’s troops and to implement French legislation and justice into the Polish territory. Napoleon also encouraged conscription, and before the signing of the Treaty of Tilsit, more than 30,000 soldiers had signed up. Three armies were created, at the head of which were Prince Josef Poniatowski, Dombrowski and Josef Zajonczek.

8 February, 1807: Difficult French victory at Eylau.

14 June, 1807: The ‘perfect’ victory of Friedland.

THE HOPE OF TILSIT: NAPOLEON AND THE MIRAGE OF THE GRAND DUCHY OF WARSAW

Despite Polish historians’ attempts to describe Napoleon’s actions towards Poland as that of a liberator, Napoleon, in his correspondence and notes of the first half of 1807, resolutely underlined his merely political interest in the country. On 23 February, he wrote to Duroc that: “The main service the Poles can do for me is to contain the Cossacks”. And again on 18 May, he wrote that Poland was simply a pawn in future peace negotiations. The Emperor, did not however forget what “individuals of the Polish army” had done for him, and in a decree on 4 June, specified that “twenty million francs should be set aside” as recompense for them.

25 June, 1807: Meeting at Tilsit between Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I. The future of Poland figured highly during their discussions. As a result of these discussions, on 7 and 9 July, the French Empire, the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia signed the Treaty of Tilsit. France and Russia formed an alliance and divided the Prussian lands between them. Napoleon’s regime was recognised and Russia joined him in his fight against Britain, by accepting the Continental Blockade.

A direct consequence of this treaty for Poland was the creation of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw on 22 July, 1807. It measured 104,000 km² and was formed with the land which Prussia had acquired during the second and third partitions of Poland in 1793 and 1795, with the exception of Danzig, with a population of 2.6 million people. It was ruled over by King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, grandson of Augustus II who had been king of Poland and Duke of Lithuania from 1733-1763. However, Frederick Augustus had very little power and was rarely in the Duchy, so the real power remained in French hands, namely Marshal Louis Nicholas Davout, who was Governor-General of the Duchy. The Polish nobility were keen for their old Constitution of 3 May, 1791 to be applied, but Napoleon installed his own Constitution instead, largely based on the French model, including a Council of State. This Constitution included liberal ideas, previously unseen in Poland, such as divorce and civil marriage, the abolition of serfdom and equality between all men before the law. The Code Napoléon was also introduced. The Continental Blockade was implemented in the Duchy, as it had been in all the other vassal states of France. The Duchy of Warsaw was mainly a military base, which served as a barrier between the French empire and Russian interests in Eastern Europe. Its army, under the command of Prince Joseph Poniatowski, was also under French power.

9 March, 1808: Frederick Augustus I of Saxony began recruiting more soldiers for the army of the duchy. Soldiers had to be between twenty-one and twenty-eight years old. Teachers, clergy and Jews were dispensed this military service.

19 April, 1809: Whilst the French troops (including a strong Polish contingent) were away fighting in Spain, Austria tried to take advantage by attacking Bavaria and the Duchy of Warsaw (which was consequently short of armed forces). After the first Battle of Raszyn, Austrian troops successfully invaded the Duchy of Warsaw, which Josef Poniatowski and his men were forced to abandon. Following this humiliating defeat, Poniatowski retreated to Galicia and mounted an insurrection, forcing the Austrians to evacuate Warsaw. On 14 October, after Napoleon’s victory at Wagram, Austria and France signed the Treaty of Schönbrunn, ending the campaign of Austria. Among other sanctions, Austria lost part of its territory, including Krakow and Lublin, to the Duchy of Warsaw. Poniatowski’s role in events was recognised by Napoleon, who made him Grand-officier of the Légion d’honneur.

January, 1810: Diplomatic relations between France and Russia were becoming tense. Russia, through its ambassador Prince Alexis Kurakin and its chancellor Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantsev, was keen for the French Emperor to formally declare that he had no intention of re-establishing the kingdom of Poland, but the Emperor refused. Armand de Caulaincourt (French ambassador to Russia) and Rumyantsev agreed on a draft convention that banned the restoration of the independent Polish state. Napoleon however rejected it. In a letter dated 24 April, 1810, Napoleon argued that any declaration against an independent Polish state had to be met with a Russian declaration against the restoration of the Kingdom of Sardinia. By July 1810, Napoleon was refusing point blank to make any sort of declaration: in his meeting with Prince Alexis Kurakin, as reported in volume two of Vandal’s Napoléon et Alexandre (pp.417-424), he declared that “French blood will not be spilt fighting for Poland, but nor will it be spilt fighting against this unhappy nation. It would be utterly demeaning to my person to make that commitment or any such similar one.”

Mid-1810: This clash over Poland led to Russian attempts to re-negotiate the Tilsit agreement. However, Kurakin’s lack of authorisation to discuss the articles of any potential alliance allowed Napoleon to dismiss any further discussion on the matter.

End of 1810: a large number of vessels from a convoy carrying British goods and proceeding through the Baltic successfully landed in Russian ports as neutral ships or were simply left to continue their journey. Napoleon realised that Alexander was no longer respecting the Continental Blockade agreed at Tilsit, and, with more and more vessels landing in Russia, on 13 December, 1810, a sénatus-consulte was announced which formally incorporated the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck, Bremen and Hamburg into the French empire. Despite French military presence in the ports for more than four years, fraud and counterfeit were still widespread and the annexation was intended to strengthen the blockade along the Baltic.31 December, 1810: the Russian tsar announced a ukase (proclamation) decreeing that goods (other than those of British provenance) could once again enter Russia via its ports, whilst imports entering the empire over land (the majority of which was of French origin) would be hit with heavy duties.

January, 1811, Alexander I began a correspondence with Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, the celebrated Polish diplomat, close personal friend to the tsar and former Minister of Foreign Affairs at the Russian court. The Russian tsar began exploring ways to begin an offensive against the French, one of which was to try and use Czartoryski’s patriotism and weight among his Polish countrymen to convince the Poles that an alliance with the Russians would bring about the reconstitution of a Polish Kingdom. Uncertainty among Polish leaders regarding Russia’s motives was to prove a stumbling block, however, and it did not take long for the French authorities to learn of Alexander’s plans. By the spring of 1811, the project had been shelved.

30 December, 1811: War between France and Russia became more and more imminent as Russia began to look towards Turkey and the Duchy of Warsaw. Napoleon reorganised his army, integrating the Polish troops into his own and taking on their costs. The forces from the Duchy of Warsaw were still led by Prince Josef Poniatowski. A few months later, the troops were ready to attack, and Napoleon’s coalition army began to advance towards Russia in June 1812.June, 1812: Alexander I had three Russian armies positioned to guard the western frontier. He was the overall commander of these armies, and was installed in Barclay de Tolly’s headquarters near Vilna. On 24 June, the Grande Armée crossed the Russian border and the Russian armies were ordered to withdraw. The French (and Polish) forces followed them, until they reached Moscow on 15 September, 1812, where they stayed for a month.

28 June, 1812: the Polish Parliament was given permission to vote a motion which aimed to restore the kingdom of Poland. On this date, the General Confederation of the Kingdom of Poland was formally established, and Prince Czartoryski was named Marshal of General Council of the Confederation. The government was similar to that of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The confederation did not last a year as Russian occupation of 30 April, 1813 put an end to it.

December 1812: After Napoleon’s brief occupation of Moscow, the remnants of the Grande Armée re-entered the Duchy of Warsaw. The Polish troops had suffered colossal losses; of the 35,000 men Poniatowski left with, only a few hundred returned. Napoleon rushed back to Paris in order to form a new army. In January 1813, the Russian army entered the Duchy of Warsaw, chasing the remnants of the Grande Armée and successively occupying the territories of Lithuania and of the Duchy. On 5 February, the Polish government left the capital. A month later, the Tsar established a Supreme Council, mostly made up of Russian generals, to guarantee Russian control. From this time, the Duchy of Warsaw existed in name only as it was under full Russian domination. The fate of the Duchy remained uncertain as other powers such as Prussia and Austria were keen to regain Polish territories.

After the disastrous Russian campaign, Napoleon began to be threatened from all sides. The Russian army continued to press on towards the west. On 17 March, 1813, Prussia declared war on France, in June Napoleon lost Spain to the Duke of Wellington and on 12 August, Austria declared war on France. Poniatowski had gathered together the surviving Polish soldiers after the retreat from Russia, and he now followed Napoleon to Leipzig, only to drown in the river Elster during the battle of Leipzig (16-19 October, 1813).

30-31 March 1814: Fall of Paris. From 4 – 11 April, Napoleon abdicated as Russian troops camped on the Champs Elysées.

18 September, 1814 – 9 June, 1815: The Congress of Vienna, held to discuss the re-organisation of Europe, divided the duchy of Warsaw between Prussia, Austria and Russia. Only Krakow remained autonomous. Russia created the Kingdom of Poland, which was allowed its own Constitution. However, this constitution was frequently violated by the Russian powers. This was to be the fourth and final partition of Poland. Poland would not find independence for another hundred years.

PH, LS. August 2014

-

Biographies

– ALEXANDER I (1777-1825)

– BIGNON, Louis-Pierre-Edouard (1771-1841)

– CZARTORYSKI, Adam Jerzy (1770-1861)

– DAVOUT, Louis Nicolas (1770-1823)

– DE PRADT, Dominique-Georges Dufour

– DOMBROWSKI, Jan Henryk (1755-1818)

– KOSCIUSZKO, Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura (1746-1817)

– PONIATOWSKI, Josef, (1763-1813)

– WALEWSKA, Countess Marie, née Laczynska, (1786-1818)

– WYBICKI, Josef (1747-1822)

The Duchy of Warsaw

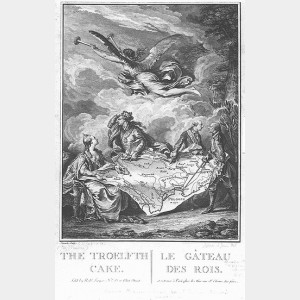

Also called The Troelfth Cake (probably a misspelling of Twelfth Cake), this is an allegory of the 1st partition of Poland. This engraving was created in 1773 by Noël Le Mire. It shows the rulers of the three countries (Catherine II of Russia on the left, Frederick II of Prussia and Emperor Joseph II of Habsburg on the right) dividing up parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between themselves.To the right of Catherine II is Stanislas Augustus Poniatowski, the last king of Poland. The angel above represents the triumph of the sovereigns, who have added to their territory, whilst avoiding conflict. The drawing gained notoriety in contemporary Europe, and was even banned in several European countries.

Also called The Troelfth Cake (probably a misspelling of Twelfth Cake), this is an allegory of the 1st partition of Poland. This engraving was created in 1773 by Noël Le Mire. It shows the rulers of the three countries (Catherine II of Russia on the left, Frederick II of Prussia and Emperor Joseph II of Habsburg on the right) dividing up parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between themselves.To the right of Catherine II is Stanislas Augustus Poniatowski, the last king of Poland. The angel above represents the triumph of the sovereigns, who have added to their territory, whilst avoiding conflict. The drawing gained notoriety in contemporary Europe, and was even banned in several European countries.