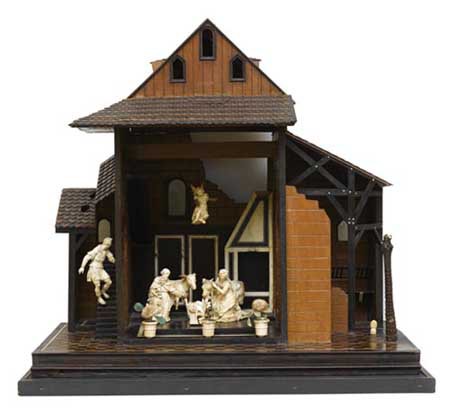

Although this is an object of religious devotion, it is also a true work of art. With its finely executed ivory figures, its ebony and mahogany decoration, and its elaborate composition, the Bonaparte family’s nativity scene is one of the Musée Nationale de la Maison Bonaparte’s most fascinating pieces.

The exceptional quality of the scene’s execution is evident in the ivory figures’ finely depicted postures and expressions, the detail on the Virgin Mary’s hair, and the rendering of folds in their clothing. The decoration of the barn is also perfectly composed, the whiteness of the ivory standing out brightly against the dark ebony background, a lovely combination with the checkerboard design on the floor of the scene.

The masterful layout of the nativity scene forces the viewer to observe all the details of the group closely; it is impossible to see the whole scene with only one look. For the viewer looking at the scene from a frontal point of view, a wooden wall on the right of the composition hides one of the figures from sight. This viewer, drawn in first by the nativity scene, lingers to look at the character on the left going down the steps, watching the scene through a window. Following the direction of his gaze, having regarded the Holy Family, the viewer also discovers the hidden character on the right: it is a shepherd approaching the child with a lamb in his arms. He is distinguished by his large hat and shoulder bag. Only then does the viewer realise that the scene depicts the episode of the Adoration of the Shepherds.

The proportions of two of the figurines, the young man looking through the window and the shepherd, are elongated in a fashion evoking mannerist representations of the latter part of the sixteenth century, an impression reinforced by the unsteady posture of the young man on the stairs. In contrast, the representations of Joseph and Mary are more “monumental” despite their small scale, and Mary especially evokes a Baroque aesthetic. These details allow the piece to be dated to the late 16th or early 17th century.

One version of the Bonaparte nativity scene’s provenance comes from an account by Larrey, which states that this scene was a gift from Napoleon to his mother on his return from Egypt. Larrey notes: “For his mother he had brought back, among other objects found in the East, a nativity scene made of ebony and mahogany, whose ivory figures were very finely crafted. This curious object was an example of the art and industry of Syria.”

In spite of Larrey’s claim, no comparable objects have been found in the Near East. The scene is also very different from Neapolitan nativity scenes, in which figurines’ faces and hands are made of ceramic and supported by iron frames, and in which their clothes are made of real fabrics.

It is in fact in Southern Germany that the most similar nativity scenes can be found, in terms of manufacture and materials used. Sybe Wartena, of the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum (Munich) – a museum which holds one of the world’s most important collections of nativity scenes – supports this analysis of its providence and compares its composition to the style of the Weilheim school, and also to the works of the Bavarian court ivory sculptor Christof Angermaier (1580-1632), who was based in Munich. By this account the barn would be a later addition and would likely date from the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Today, Larrey’s claim assumes less prominence and it is though that the scene was likely a gift from Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul, to his Ramilino cousins around 1802.

Finally we should note that in 1810 the writer G. Lenôtre (real name Louis Gosselin [1855-1935]), nicknamed “the great historian of inconsequential history”, published his Légendes de Noël, contes historiques (Christmas Legends, historical tales) in Paris, among which was the story The Star, which tells a completely invented story about the nativity scene of Ajaccio. Lenôtre imagines that it is the work of a shepherd, a cousin of the nurse Illari, who on Christmas Eve brings it from the mountain to Signora Letizia (Napoleon’s mother). But the Bonaparte boys will not stop taking it apart, crowning themselves in the crowns of the magi (!) and flourishing the star which has guided them toward Bethlehem. The author concludes by highlighting the prophesying aspect of these children’s games (the little boys will become kings, and the star is likened to the comet which had crossed the sky on the Emperor’s death). A drawing reproduced on page 13 of n° 1305 in Pèlerin illustrates this legend.

Text by Jean-Marc Olivesi, Chief Curator of the Musée de la Maison Bonaparte, March 2014. Translated by Emma Simmons, December 2014.