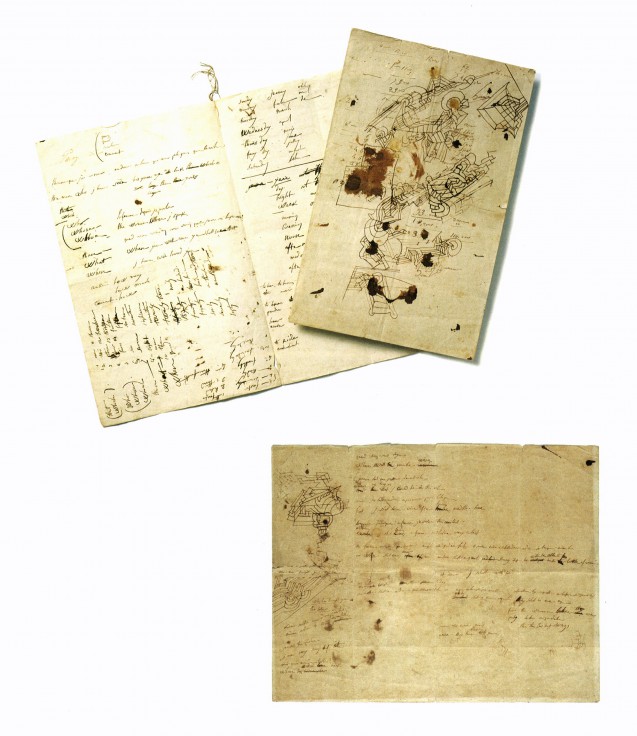

These eight pages of writing, covered in the impatient scribbles of a man determined to learn the language of his captors, are some of the most evocative documents we have from Napoleon’s time on Saint Helena. His arrival on the British outpost in October 1815 heralded an exile that was not only geographic, but also linguistic: in addition to the oppressive heat, the often continuous rain, the stifling atmosphere of the Longwood plateau, Napoleon was “imprisoned in the middle of this language”, isolated in the South Atlantic on an island where news was scarce, and what books or newspapers could be found were almost all printed in English. And so, three months to the day after his arrival on Saint Helena, Napoleon decided to learn English.

One of the most valuable sources for the fallen emperor’s English lessons is Emmanuel-Auguste-Dieudonné-Marius-Joseph Las Cases’s Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène, in which Las Cases records fifteen months of day-to-day life on the island. In fact, Las Cases notes that he had already given Napoleon two English lessons on board the Northumberland (between 23 and 25 August, 1815, when the ship was moored off Madeira), but since almost all the ship’s officers spoke French, the project had been abandoned. It was Las Cases, on 16 January, 1816, who suggested to Napoleon during a walk around the gardens at Longwood that he could easily learn English with a little practice. Their first lesson took place the following day, on 17 January.

These sheets of English lessons date from this period of Las Cases’s instruction. They contain both lists of basic vocabulary – numbers, days of the week, months, times of day – and sentences written out in French and translated beneath into English. These phrases bear poignant witness to the frustration Napoleon felt in exile: “Quand serez vous sage? – When will you be wise / jamais tant que je suis dans cette isle. Never as long as j should be in this isle / Mais je le deviendrai après avoir passé la ligne / But j shall become wise after having passed the line / Lorsque je débarquerai en France je serai très content – When j shall land in France j shall be very content…” It is tempting to read a refusal of exile in these sheets, both in the sentences themselves, and in Napoleon’s insistent use of “j” (as in the French “je”) rather than the English “I”. They demonstrate, too, that his family was very much on his mind at Longwood: ““my wife shall come near to me,” he translates, “my son shall be great and strong if he will be able to trink (sic) a bottle of wine at dinner j shall [toast] with him…”

Accounts of the Emperor’s English are mixed. Las Cases often praises him as a quick learner, but on other occasions notes the idiosyncrasies of his pronunciation. Betsy Balcombe described Napoleon’s English as “the oddest in the world.” But whatever level he attained, these ink-smeared sheets of paper bear witness to a remarkable achievement: a fallen emperor determined to learn the language of his greatest enemies and his jailors.

Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, tr. Marie de Bruchard, October 2014

You can read Peter Hicks’s article about Napoleon’s English lessons here.