On 11 June, 1812, Josephine commissioned from the sculptor Canova a work representing the Three Graces. The Empress already owned several pieces of art by the artist, including a dancer, a copy of a statue of Hebe and a bust of Paris, all of which she kept in her collection at the Château de Malmaison. Canova had already depicted members of the imperial family in his works, but curiously, Napoleon’s first wife had never featured. In 1802, he had been summoned to Paris to complete his statue of the First Consul. However, the resulting art-work, Napoleon as Mars the Peace-bringer, was poorly received by the French Emperor, who was shocked by the heroic nudity present in this allegorical representation. The wives of Murat and Lucien also were also immortalised in busts by Canova which combined realism and the neo-classical canon. This inspiration, taken from Antiquity, dominates the great portraits of Pauline as Venus victorious, of Madame Mère as Agrippina and Marie Louise as Concordia.

Josephine never had the pleasure of seeing the work that she had commissioned. On her death in 1814, the statue was still to be completed, and it was only in 1816 that Eugène, her son, received the marble depiction. As with the other statues by Canova in Empress’s collection, the Three Graces was acquired by Tsar Alexander I, and the piece can today be admired at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. A second version, completed between 1815 and 1817, was jointly acquired in 1994 by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh.

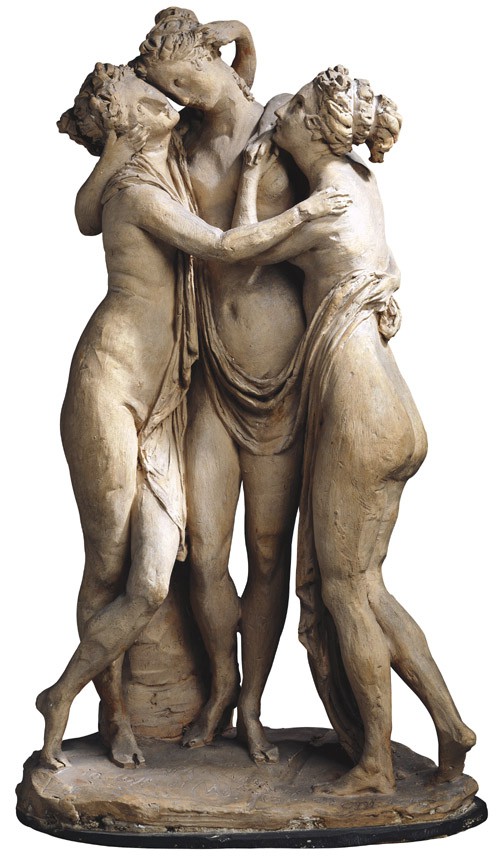

The early draft of the Three Graces, sculpted in fired clay, is part of the long and complex process that went into the creation of the art-work. The date of the draft, which predates Josephine’s commission, indicates the long gestation period of the statue. Since Antiquity, the Three Graces have been popular with artists. In painting, Raphael, Regnault and Rubens all adopted the same representational conventions: three young, nude women, standing in a line. The middle woman has her back to the viewer, her arms spread towards her two companions, either side of her. Canova stepped away from this vision to create a tightly-grouped representation of the Graces in which imitation of nature is allied with Antiquity’s ideal.

The draft version was offered by the sculptor to Juliette Récamier, probably in 1813. As with many of the works of art that surrounded this famous young woman, this clay sculpture was more a testament to the friendship that existed between her and the artist. They had met in Rome when Juliette visited the artist’s studio, and she soon became as much a source of inspiration as a friend to Canova. In 1849, the statue was left in Juliette’s will to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, following her death in the same year.

Karine Huguenaud (tr. & ed. H.D.W.)

Elodie Lerner’s review of the exhibition “Juliette Récamier: muse and patron of the arts”, and the catalogue that accompanies it, is available on napoleon.org.

April 2009