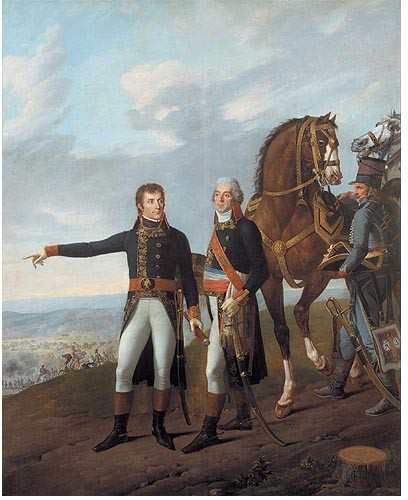

The victory at Marengo was celebrated in many different works of art, both paintings and sculptures, some commissioned and giving the official propaganda, and others the personal initiative of artists with an eye to the main chance hoping to attract the favourable influence of the victor and new master of France. This huge painting here falls into that second category and was executed shortly after the battle on 14 June 1800. On completion it was exhibited by Joseph Boze in Amsterdam and London, with the artist claiming sole credit for the work.

When the painting was shown in London in the summer of 1801, the ambassador of France to England, Louis Guillaume Otto, reported to Talleyrand “there is not one man of leisure here who does not wish to see Paris, and above all the First Consul, and the portrait painted by Boze has created a great sensation”. At the same time a subscription for an engraving by Anthony Cardon was launched for the huge sum of four guineas (including a deluxe version using the stipple technique in colour which cost double), and the painting went on to Bath and Bristol, presumably with aim of promoting the planned subscription.

When the news reached France, a violent quarrel arose in the press. In the Moniteur Universel, dated 11 Thermidor, An IX (31 July, 1801), the painter Robert Lefèvre claimed agressively that it was not the work of Boze. Boze’s wife ran to his defence, refuting all the accusations and stating that her husband was “the author of the design, the sketching and the execution of the principal figures”. In his reply, Robert Lefèvre cited several witnesses, Carle Vernet (of course), but also Guérin, Landon, Mérimée and Van Dael, all of whom affirmed the opposite. The dispute appeared to end there, at least from a public point of view, and the painting remained in the possession of Boze.

Portraitist of Louis XVI and the royal family, Boze perhaps did this in an attempt to raise himself from the oblivion into which he seemed to have fallen, after the Revolution during which he had spent several months in prison and then in exile. Once the furore calmed down, he once again disappeared from public view not to reappear until the Restoration. Whether it was a confidence trick or artistic rivalry, the quarrel with Robert Lefèvre was never to be satisfactorily resolved. It does indeed appear that they collaborated – before the Revolution both artists were in the habit of working together for standing portraits -, and the faces of Bonaparte and Berthier are quite obviously the work of Boze. Carle Vernet’s role would also seem to have been more than just the battlescene, which in itself was not finished but claimed by Robert Lefèvre. The fine group of horses would seem to be very much Vernet’s brushwork. One thing for certain, in this painting which has not yet given up all its secrets, is that the bay mare has been identified. It is in fact La Belle, the horse which Bonaparte rode at the Battle of Marengo. She had found favour with many artists and was frequently used as a model, notably by David for one of the versions of his celebrated ‘Crossing of the Great Saint Bernard Pass’.

(additional information added November 2017 by Peter Hicks)

This painting is on a long-term loan from the Fondation Napoléon Collection to the Musée de l’Armée in Paris since 2012.