After years of enduring the arbitrary whims of the July Monarchy Salon juries, the “eternally rejected” Théodore Rousseau achieved fame during the Second Republic. It was the Second Empire however that would grant him the official recognition he so craved. He was made knight of the Légion d’honneur in 1852 and officer in 1867, and in 1865 he was even invited to one of the famous séries de Compiègne [weekend retreats involving the great and the good of imperial society, ed.]. As one of the founders of the Ecole de Barbizon (named after the tiny village bordering the forest of Fontainebleau where he began painting during the winter of 1836-1837), Rousseau came to be regarded as one of the great landscape artists of the nineteenth-century. This insatiable and observant artist pursued his pictorial experiments – some of which presaged the impressionist movement – until the end of his life in 1867.

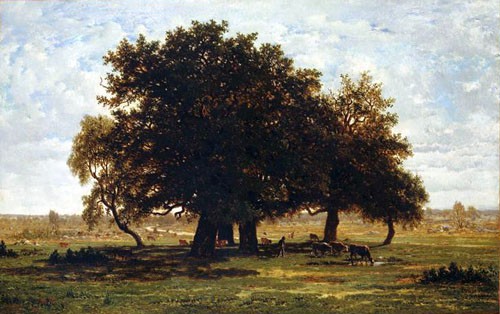

The painter, who described himself as “man of the forests”, followed only one religion, that of nature. He dedicated his time in Fontainebleau to contemplating the natural world, producing numerous preparatory drawings and studies which he would subsequently rework into completed designs. Trees in particular played a central role in his work. Rousseau treated them as beings, to the extent that he described the paintings he made of them “portraits”. If so, then this particular painting, a scene featuring multiple oaks in the area known as the Gorges d’Apremont which he presented at the Salon in 1852, is most certainly a group portrait.

Under a dappled sky, the majestic oaks stand tall in the summer heat, proffering their shade to the shepherd and his flock. As with all of Rousseau’s paintings, the human presence in this scene is minimal. Yet this state of disproportion is not all-enveloping. The Romantic construction of this landscape is replaced by a naturalism that does not seek to seduce. The artist is more interested in offering a realistic depiction of the unrelenting midday sun, and of the way in which the light falls. The painting was exhibited at the Universal Exhibition of 1855 alongside twelve other compositions by the painter. It was subsequently bought by the Duc de Morny in 1865.

In 1852, Rousseau’s pantheistic communion with nature led to his petitioning the emperor through the Duc de Morny. Protesting at the commercial exploitation of the trees and rocks in Fontainebleau forest – notably in Bas-Bréau near his home in Barbizon – the artist described the felling as “carnage” and “a death sentence” and called for protected status for the area. A study was carried out on the forest as a result of the petition, and in 1863 the emperor signed a decree setting aside 1097 hectares “for the exclusive enjoyment of the rambler and the artist”. Thus arguably the world’s first nature reserve was created in Fontainebleau forest.

Karine Huguenaud (tr. H.D.W.)

March 2012