When the Scottish painter William Quiller Orchardson exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1892, he was sixty years old and had established a long career, which began at the age of fifteen when he entered Edinburgh’s renowned art school, the Trustees’ Academy. Orchardson was a talented portrait artist but one of his favourite genres was the painting of atmospheric historical scenes. His paintings did not represent big military or political events: they translated an atmosphere of a bygone era, according to one of the principles taught him by his teacher Robert Scott Lauder (1803-1869) who was himself a master of the genre. Some of Orchardson’s paintings therefore have a explicit historical and even French theme such as Voltaire (1883), or Le mariage de convenance (1883), A Revolutionist (1885). Other works evoke the Empire style, using period furniture and costumes to describe the life of that time: A social Eddy (Left by the Tide) (1877), The Lyric (1904).

Orchardson greatly admired Napoleon and deplored the cruelty of his confinement in St Helena at the end of his life. He was one of a number of artists, both in France and Britain, led by Paul Delaroche, who, in contrast to the militarist paintings of Napoleon by artists of the First Empire, chose to depict a more intimate and thoughtful side of Napoleon’s character, as demonstrated in his 1880 painting Napoleon on board Bellerophon.

St. Helena 1816 – Napoleon dictating to Count Las Cases the Account of his campaigns was acquired by William Lever, a wealthy British Liberal industrialist who made his fortune with soap and palm oil, and was also a pioneer of pictorial advertising in the last decade of the nineteenth century. A great lover of history painting, this Napoleon enthusiast was doubtless attracted by the originality of Orchardson’s composition.

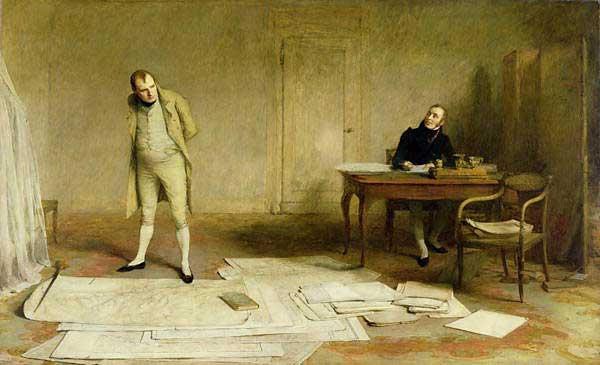

The work which represents Napoleon writing his memoirs is indeed quite unusual within the context of the Napoleonic iconography. Throughout the nineteenth century, most of the paintings of Napoleon in exile showed him sick, either static or in bed such as The Emperor dictating his memoirs to Gourgaud by Charles Steuben, or Napoleon on St Helena dictating his memoirs to Count Las Cases by Ary Scheffer, or in this anonymous engraving of 1828. Orchardson on the other hand chose to place the deposed Emperor dynamically, busy with the details of his maps, and explicitly mentioned in the title the glorious theme of the dictation it represented: war. He therefore focuses his attention on Napoleon’s triumphant past while highlighting two of his traits of character that the Napoleonic legend had preserved: his obsessive meticulousness and agitation. Frowning, Napoleon appears stopped in his tracks as he tries to recall a detail in the sequence of a battle. Las Cases, appears suspended, his pen poised, hanging on the words of the Emperor. The room appears stripped bare unlike Napoleon’s actual bedroom in the house at Longwood. It echoes the downfall of the great man in 1816, but more importantly allows the viewer to focus his attention on the faces, especially the eyes, of the two protagonists in this theatrical scene. Their eyes do not cross but induce two movements – the downward-looking gaze of Napoleon; and the upward-looking one of Las Cases – reflecting the social positions of the two men: the master and the servant.

When the painting was exhibited in 1892, critics admired its ’emptiness full of atmosphere which Mr.Orchardson so loves to depict’. Whilst he was praised by some for the subtlety of his palette – ‘practically a study in whites’ – others called into question the Emperor’s appearance: ‘was he not fatter, heavier, less fit for locomotion in 1816 than he looks here?’. The Times praised the painting of the accessories, particularly the maps on the floor, supposedly the very ones used by Napoleon including the one of his 1805 Prussian campaign that Orchardson had found at Stanford’s, the well known London map shop.

William Lever was not content merely to acquire Orchardson’s painting: he also bought part of the First Empire furniture William Orchardson used as props for his genre paintings. He also acquired other objects supposed to have been owned by Napoleon or his family. In the art gallery which he dedicated to his late wife, the patron built an entire room devoted to Napoleon. In the “Napoleon Room” at the Lady Lever Museum, which has recently been renovated, Orchardson’s painting has pride of place.

Marie De Bruchard, October 2015,

translation Rebecca Young