At the same time as the huge Parisian triumph of the Exposition Universelle of 1867, international news arrived, casting a terrible pall over the fête. It was on 1 July, the very day on which the imperial couple were to distribute the prizes, that Paris learned of the execution of Maximilian, the puppet emperor set on the Mexican throne by Napoleon III, which had taken place in Queretaro (north Mexico). This was the tragic conclusion to Napoleon III’s catastrophic Mexican expedition.

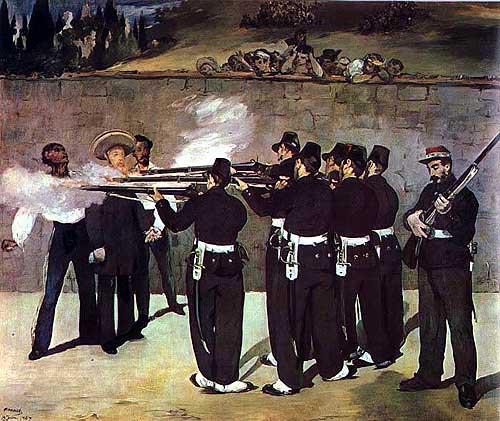

Like many of his contemporaries, Manet was greatly struck by the event. Indeed, in what was a rare foray into the historical genre, he chose a subject related to current affairs which had been largely avoided by other artists because of the censor. Taking his inspiration from Goya’s Tres de Mayo, a summary condemnation of another Napoleonic war, Manet chose the moment where the tension was at its highest: the firing squad execution of Maximilian and that of the two generals Mejia and Miramon. He painted his first version almost immediately, giving what he imagined the scene had been like, the soldiers in mexican costumes and sombreros. This ‘rustic’ vision was was however soon to change as further details of the event reached Paris, giving Manet a documentary basis for his work. In the last version, the soldiers’ uniforms had become so formal that they resembled those of the French army, a direct allusion to Napoleon III’s role in the tragedy. This bitter criticism was not lost on contemporaries, as was noted by Zola: “You can understand the censors’ shock and anger. What! an artist dared to put before them such cruel irony: France executing Maximilian!”. On the Mexicans, in the background on the wall, reveal any of the horror of this execution scene. The coldness of the soldiers is heightened by the figure to the right turned towards the viewer. His disproprtionately large hand reaches for the trigger – he is one whose job it is to administer the coup de grace. Manet must have read this in the newspapers: one soldier not belonging to the execution party finished Maximilien off at close range.

Although he was greatly attached to this work, Manet never managed to exhibit it during the Second Empire. And whilst the walls of the Salon of 1868 were covered in painted representations of the Mexican expedition, all favourable to the regime, Manet’s masterpiece was banned.

Karine Huguenaud (tr. P.H.)

January 2007