Whilst photography was initially a luxury good, reserved for only the wealthiest clientele, during the Second Empire it became accessible to a much wider public, leading to the development of the “visiting card” portrait, patented by Disdéri in 1854. Indeed, the fact that in 1860 more than 200 photographers had boutiques in Paris shows that photography had become quite popular, notably with the middle classes in search of social recognition. According to Nadar, Napoleon III himself was the origin of the phenomenon. Fully aware of the political utility of such images (small format meant that they could be produced and sent out in large quantities), the Emperor posed for photographers many times and his “visiting cards” were an unprecedented commercial success. It is true that the imperial couple still commissioned painters to execute official portraits, but after 1856, the date of the Prince impérial’s birth, official photography was perceived as the most efficient method of propaganda. Very often the Emperor and Empress were taken wearing middle class clothes and adopted poses less formal than those of their painted portraits. In their deconsacration of the image of the sovereign distant from his people, these photos played on themes such as intimacy and proximity, particularly in the many family scenes showing the parents with their child, thus creating the possibility that viewers could identify with the couple, increasing popular support.

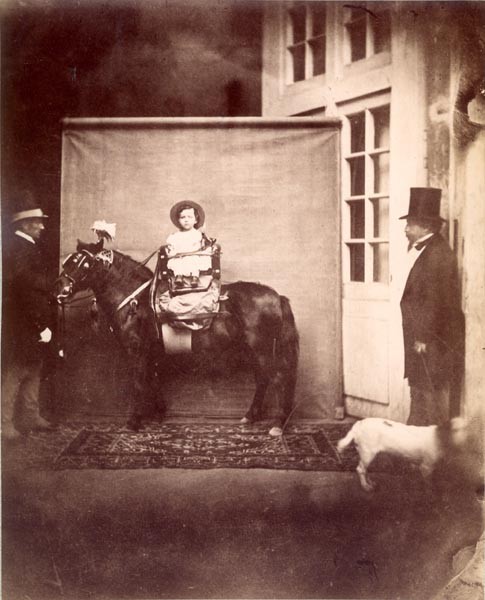

The photograph of the Prince Impérial here is one of such photographs. Executed by Meyer and Pierson circa 1859 – the Prince does not appear to be more than 2 or 3 years old -, this photo shows a sitting for an image destined for the mass market. But here the photographers have taken us back stage of the formal photo of the little prince firmly strapped onto his saddle against a backdrop. The wider angle shows (on the left) the footman restraining the animal, and (on the right) Napoleon III, watching the photo session just as any father would. A dark and stiff figure, in a black morning coat and top hat, reduced to the role of walkon, the emperor has a dog on a lead – indeed the out of focus quality gives the photo a feeling of a real ‘shapshot’. This moment seized – a photograph within a photograph – takes us into the back passageways of the imperial court. By no means official propaganda, this extraordinary composition is a charming and fascinating ‘out-take’.

A contemporaneous print of this same scene (clearly made from the same glass negative, but slightly cropped) can be found in the collection of the Jean Paul Getty Museum.

Karine Huguenaud (tr. P.H.)

June 2005