Although the Second Empire period was a financially difficult time for Monet, it nevertheless failed to shake his belief in a new, modern style of painting entirely disassociated from the masters of the past. Described by Bazille as “the best of all of us”, Monet would go on to lay the foundations of impressionism. Rebellious, radical and passionate, he was guided by one thing: a new perception of nature, composed of sensations and visual impressions, painted in a direct and frank manner. 1866, a successful year which saw Camille or The Woman in the Green Dress – a full length portrait of his wife, improvised over the course of just a few days – well received at the Salon, proved a temporary high point in Monet’s career. Soon afterwards, however, financial difficulties, fuelled by inter-family conflict, once again beset the artist.

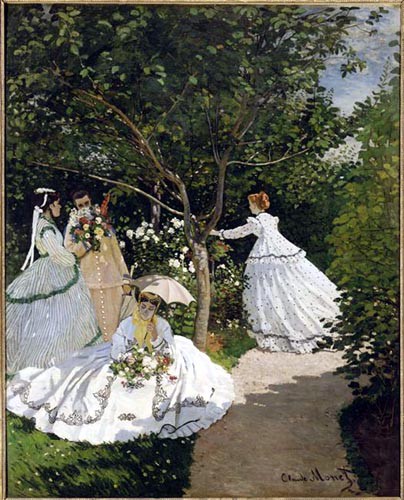

That same year, Monet threw himself into a composition intended to resolve the issues of form that he had met during the painting of his Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which he failed to complete. Daily contemporary life once again served as the subject for this new composition: a gentle image of four women dressed in light crinoline, picking flowers in a garden dappled in sunlight. His Women in the Garden, almost full-size, was sketched entirely en plein air, thus breaking from the traditions that had previously governed the composition of large scale canvases. He did however continue to abide by the guiding principles inherent in pleinairism: spontaneity and an honest observation of nature. The palette is bright and lively, without any sort of modulation in tone, and the reflection of the light is striking. The broad technique and visible brushstrokes found in the painting’s hues and shadows preserve the impression of incompletion in the preliminary sketch. These qualities were to provide ample provocation for those sitting on the jury of the 1867 salon who, proving themselves to be particularly harsh in a Universal Exhibition year, rejected the painting.

Despite a petition calling for a new “Salon des Refusés”, launched by Bazille, signed by sixty-odd rejected artists including Monet, Manet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley and Jongkind, and addressed to the Comte de Nieuwerkerke – the surintendant of the Académie des Beaux-Arts – on 30 March, 1867, the idea was dismissed. Attempts to hold a counter-exhibition also failed through lack of funds. As a result, Women in the Garden remained hidden in Monet’s studio. Destitute and with his first son born that same year, the artist was forced to turn to his friend Bazille for help. The latter ended up purchasing the painting for 2,500 Francs, which he paid in monthly instalments of 50 Francs!

In 1921, the French state paid 200,000 Francs for the work – which was by now back in Monet’s possession – and the painting was hung in the Musée du Luxembourg, before being later transferred to the Musée d’Orsay.

Karine Huguenaud (tr. H.D.W.)

November 2010