Which is your favourite piece in the show and why?

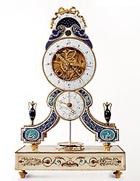

With a show of such an encyclopaedic nature, it is difficult to have just one favourite piece. One of my absolute favourite works comes from the extraordinary collections of the Fondation Napoléon. This is the Revolutionary period Skeleton Clock (c.1793-95). Aside from the complex beauty of its intricate mechanisms and exquisite enamel decoration, it tells a fascinating story of a France striving to cope with complex social changes. The clock is bilingual in nature, presenting both the old Gregorian and the new Republican or Revolutionary Calendars' respective systems of measuring hours, days and months. In addition the clock also offers a separate dial showing the phases of the moon. I am not sure whether the latter layer of information would have helped or hindered a bewildered Citoyen already challenged by competing duodecimal and decimal timekeeping systems during the last days of the Terror and the emergence of the Directory!

I love Charles-Alexandre Lesueur's watercolour of the Platypus or Ornithorynque 1802-04, which has been loaned by the Muséum d'Histoire naturelle in Le Havre. This is one of the remarkable studies of Australian fauna undertaken in Tasmania and New South Wales during the Baudin voyage of exploration to south-eastern Australia, authorised by Napoleon as First Consul in 1800. Baudin was the first European to fully map the coastline of our own region, Victoria, giving it as its first name Terre Napoléon. (What better reason for us to stage a Napoleonic exhibition here in Melbourne, Victoria?) I love to think about how in May 1802, at roughly the same time that Baudin's team were studying the then newly-discovered platypus at first-hand in Australia, Napoleon is documented as also discussing this bizarre Australian animal at a dinner held at Malmaison. It was to be a French scientist working at the Muséum d'Histoire naturelle in Paris, Étienne Geoffroy de Saint-Hlaire, who in 1803 first defined the platypus as belonging to a new genus, that of the monotreme.

And I love the uniform of the foot grenadier of the Vieille Garde that has been loaned to us, with its original mannequin from around 1900, from the extraordinary military collections of the Musée de l'Empéri in Salon-de-Provence. This is such a wonderful evocation of the classic grognard, the 'grumbler' soldier, a foot-sore battler full of complaints, yet faithful to Napoleon to the core. We have juxtaposed this visually with Canova's sublime over life-size plaster bust of the head of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, which is on loan to us from the Museo Glauco Lombardi in Parma. This creates a striking visual dialogue!

Which was the trickiest piece to install? What’s the trickiest ever piece you had to install?

The trickiest work to install in “Napoleon: Revolution to Empire” was Lorenzo Bartolini's massive bronze bust, Napoléon Empereur (1805), which has been loaned to Melbourne by the Musée du Louvre. Just over 1.5 metres high and weighing in at 1,000 kilos, this was a massive work to ship and handle, both in terms of scale and sheer weight. After discussions with the Louvre, we wanted to install this work at the same height as it would have been originally viewed when first placed above the entrance way to the refurbished Musée du Louvre (then known as the Musée Napoléon) in 1805.

The trickiest work to install in “Napoleon: Revolution to Empire” was Lorenzo Bartolini's massive bronze bust, Napoléon Empereur (1805), which has been loaned to Melbourne by the Musée du Louvre. Just over 1.5 metres high and weighing in at 1,000 kilos, this was a massive work to ship and handle, both in terms of scale and sheer weight. After discussions with the Louvre, we wanted to install this work at the same height as it would have been originally viewed when first placed above the entrance way to the refurbished Musée du Louvre (then known as the Musée Napoléon) in 1805.

The NGV worked closely with engineers here in Melbourne to ensure both that our floors could cope with the weight of this monumental bronze, as well as to design a three-metre high plinth that could support its weight. The bronze was placed atop this plinth in the main atrium of our museum with the aid of an industrial crane guided by skilled heavy-lifting technicians. Once installed at this height, what had seemed at ground-view to be a somewhat severe stylization of Napoleon as a modern embodiment of the Imperium of ancient Rome, suddenly softened, revealing a hope-filled vision of Napoleon as a fit young athlete. Set against the changing skies over Melbourne, as seen through the transparent glass roof of our atrium, Bartolini's Napoléon Empereur sets one pulse racing and spirits soaring – a suitable prelude to entering the exhibition.

The trickiest work I have ever had to install was a contemporary one, a life-sized hand-made replica of a 1975 Toyota Utility car made from a plastic skin moulded over a steel armature and entirely hand-painted with enamel and silver, aluminium and gold leaf. This work was created in 1989 by a Melbourne-based artist, Eamon O'Toole. The sculpture reproduces every element of the original car down to the last detail, with doors and bonnet that open to reveal all of the vehicle's internal parts. The sculpture is strong enough for a person to sit inside and simulate driving it, which gives an idea of its weight. For some reason twelve years ago I thought it would be a cool idea to install Eamon's work on a mirrored floor, to reveal all the final detailing that he had crafted on the vehicle's underbelly. Six of us had a one-shot chance of lifting the sculpture manually and positioning it correctly upon a slippery mirrored floor without our combined weights cracking the mirrors. It was a hair-raising nightmare at the time, but well worth the effort in the end, for the spectacular visual effect we created for the viewer.

Which is your favourite bit about making exhibitions – the catalogue or the exhibition itself?

I love both these aspects of exhibition planning, actually. With organising an exhibition there is the Sherlock Holmes aspect of searching out the whereabouts of key works that I find fascinating, along with the logistics of thinking through each aspect of an exhibition's experience from a visitor's point of view – what stories will each show tell, and in what order; and, above all, how will the show express itself visually at each step of its progression, so that it is a sumptuous physical experience for viewers. I also love the process of visiting all of an exhibition's targeted lenders, in order to explain the curatorial vision of an exhibition and hopefully persuade them to lend their individual treasures so that they can be seen within a newly constructed curatorial narrative.

I love both these aspects of exhibition planning, actually. With organising an exhibition there is the Sherlock Holmes aspect of searching out the whereabouts of key works that I find fascinating, along with the logistics of thinking through each aspect of an exhibition's experience from a visitor's point of view – what stories will each show tell, and in what order; and, above all, how will the show express itself visually at each step of its progression, so that it is a sumptuous physical experience for viewers. I also love the process of visiting all of an exhibition's targeted lenders, in order to explain the curatorial vision of an exhibition and hopefully persuade them to lend their individual treasures so that they can be seen within a newly constructed curatorial narrative.

This is something that Karine Huguenaud and I did with all of the lenders to “Napoleon: Revolution to Empire”, carefully explaining how their works fitted into the exhibition narrative that we wanted to construct.

Equally fascinating, however, is the process of conceiving and constructing an exhibition's publication. How will it reflect the physical experience of the exhibition itself? What wider themes might it also address? I always find too that it is when one comes to write the text for any publication that the true questions posed by the exhibition's thesis come to the fore, prompting further research and reading, and greatly deepening one's interest in and knowledge of the particular exhibition project.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase via the NGV online store (external link).