-

Introduction

These itineraries are aimed at nature-lovers as a guide to the perhaps unsuspected treasures the capital has to offer. Historians will also find it a particularly pleasant way of immersing themselves in the daily life of the Second Empire. Whatever your motivations, you’re sure to be surprised and captivated – and to see the city in a whole new way.

The sections below offer access to various topics providing all the practical and historical information you will need for a smooth trip through your itinerary. The ‘Practical Information’ section of this itinerary lists opening and closing times, as well as addresses and details for activities. Escapades gives a brief history of Parisian gardens including those planted before the Second Empire and in recent years. Continuation is a panorama of imperial society’s leisure time and entertainment in the lush green spaces of the city. And afterwards offers an abridged list of books on the topic.

Why a stroll through the Parisian squares, gardens, parks and woods of the Second Empire? The answer is simple: most of the capital’s green spaces were designed during this period and many people remain unaware of this remarkable historical heritage. It is as a direct result of Napoleon III’s drive and energy between 1850 and 1870 that Paris has the sumptuous gardens we still admire today.

The Emperor had a passionate interest in botany. Early on, while imprisoned at the fort in Ham after the disastrous Boulogne expedition, Louis-Napoleon passed the time by gardening: “I succeeded in tilling,” he wrote to a friend, “a small plot of land where I am busily engaged in planting seeds and bushes… Our natural surroundings offer unending resources and consolation to those whose happiness wanes”. He later expressed serious interest for landscape art. During his exile in England the future Emperor studied and admired London’s parks. He even participated in laying out the Duke of Hamilton’s gardens and designed the Brodnick Park for him, eliciting the Duke’s ironic comment, “Should he ever lose his rank, I would gladly appoint him head landscape gardener.”

The Emperor had a passionate interest in botany. Early on, while imprisoned at the fort in Ham after the disastrous Boulogne expedition, Louis-Napoleon passed the time by gardening: “I succeeded in tilling,” he wrote to a friend, “a small plot of land where I am busily engaged in planting seeds and bushes… Our natural surroundings offer unending resources and consolation to those whose happiness wanes”. He later expressed serious interest for landscape art. During his exile in England the future Emperor studied and admired London’s parks. He even participated in laying out the Duke of Hamilton’s gardens and designed the Brodnick Park for him, eliciting the Duke’s ironic comment, “Should he ever lose his rank, I would gladly appoint him head landscape gardener.”In his grand urban planning projects for Paris Napoleon III thus set aside special room for creating green spaces. For the first time in the capital’s history, a sovereign’s interest in gardens was not intended for his own pleasure or as a display of his magnificence and power, but as a means of satisfying his subjects. He aimed to develop places of respite throughout the dense urban and social fabric – “green spaces” essential in enabling the city to breathe. Like the human body Paris had its circulatory system – a geometrical grid of boulevards and avenues – and its waste disposal system – the network of sewers built under the city. All that was missing was a respiratory system. This novel concept of urban planning with a social bent led to the development or the creation of 24 squares (17 in the old city and seven in recently annexed neighbourhoods), four gardens, four parks and two woods – all for Parisians’ well-being.

Two men brought the Emperor’s vision to fruition : Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine who went down in history for having laid out a new, modern Paris, and Adolphe Alphand, a less eminent engineer who was named Director of Promenades and Plantations for the city of Paris. These two men, with the help of the horticulturist Barillet-Deschamp, the architect Davioud, and Belgrand from the Water Department, created the most magnificent and beautiful array of public green spaces the capital has ever known. Follow us now along our path through Paris, starting in the heart of the city in the Jardin des Tuileries and spiralling out to the Bois de Boulogne.

Karine Huguenaud

(September 1997)Photos © Fondation Napoléon – K.Huguenaud

[This itinerary was first created in 1997, certain information may have become obsolete].

-

Route : Squares

Square Louvois – 2292 square yards (1925 square metres)

This square facing the Bibliothèque Nationale was inaugurated at the same time as the Solférino bridge on August 15, 1859 on the occasion of Napoleon III’s celebration. The square’s simple design is laid out around the lovely Fountain of the French Rivers built in 1839 by the architect Visconti and the sculptor Klagmann.

Square Emile-Chautemps – 4714 square yards (3960 square metres)

An August 23, 1858 order announced the creation of the Square Emile-Chautemps, previously known as the Square des Arts et Métiers. It was designed during construction carried out in the wake of work done four years prior to the building of the Boulevard de Sébastopol. After its inauguration, the journal L’Illustration characterized it by saying, “It belongs to the category we could call noble.” And in this respect, the square’s organisation is typical of formal gardens. Divided into equal sections, the garden emphasises symmetry with orderly alleys lined with chestnut trees and two oval pools decorated with bronze sculptures. These bronze figures were designed by Davioud and sculpted in 1860. To the left, across from the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, allegories of Agriculture and Industry are the work of the sculptor Gumery (1827-1871). To the right, Mercury and the Music are by Ottin (1811-1867). The ornamental patterns were designed by Liénard.

An August 23, 1858 order announced the creation of the Square Emile-Chautemps, previously known as the Square des Arts et Métiers. It was designed during construction carried out in the wake of work done four years prior to the building of the Boulevard de Sébastopol. After its inauguration, the journal L’Illustration characterized it by saying, “It belongs to the category we could call noble.” And in this respect, the square’s organisation is typical of formal gardens. Divided into equal sections, the garden emphasises symmetry with orderly alleys lined with chestnut trees and two oval pools decorated with bronze sculptures. These bronze figures were designed by Davioud and sculpted in 1860. To the left, across from the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, allegories of Agriculture and Industry are the work of the sculptor Gumery (1827-1871). To the right, Mercury and the Music are by Ottin (1811-1867). The ornamental patterns were designed by Liénard.

The Square Emile-Chautemps is particularly noteworthy not only for its layout, but also for its monuments. In the middle, a commemorative column of Jura granite was erected in honour of the Second Empire’s victorious armies. The base portrays four major triumphs of the Crimean War: Alma (September 20, 1854), Inkermann (November 5, 1854), Tchernaïa (August 16, 1855) and Sébastopol (September 8, 1855).

Facing the square, the Théâtre de la Gaîté Lyrique provides an excellent example of Second Empire architecture. Built in 1862 by Hittorff and Cuzin to replace the Théâtre de la Gaîté on the Rue du Temple, the theatre was under the direction of Offenbach from 1873 to 1875. The façade is decorated with composite pilasters which frame the five arcades, mounted with red marble columns, on the first story.Square du Temple – 9482 square yards (7965 square metres)

Opened to the public in 1857, the square occupies part of what was once the medieval Knights Templars’ precinct, sadly transformed into a state prison from 1792 to 1808. Louis XVI and his family were held here during the French Revolution. In 1809 Napoleon gave orders to destroy much of the fortress, and the Temple tower was knocked down in 1811. All the buildings were demolished to make way for the present-day square. The Square du Temple is a small English garden – almost an arboretum with all the rare species it houses – and includes many characteristic elements of the Second Empire: a man-made ornamental pond lapping over rocks from Fontainebleau, a gate designed by Davioud, a “public convenience” and a bandstand. Of note is the stone statue of the poet and cabaret singer Béranger, a work by a contemporary sculptor named Lagriffoul.

Opened to the public in 1857, the square occupies part of what was once the medieval Knights Templars’ precinct, sadly transformed into a state prison from 1792 to 1808. Louis XVI and his family were held here during the French Revolution. In 1809 Napoleon gave orders to destroy much of the fortress, and the Temple tower was knocked down in 1811. All the buildings were demolished to make way for the present-day square. The Square du Temple is a small English garden – almost an arboretum with all the rare species it houses – and includes many characteristic elements of the Second Empire: a man-made ornamental pond lapping over rocks from Fontainebleau, a gate designed by Davioud, a “public convenience” and a bandstand. Of note is the stone statue of the poet and cabaret singer Béranger, a work by a contemporary sculptor named Lagriffoul.Square des Innocents – 1036 square yards (870 square metres)

Incorrectly dubbed a garden square, the Place des Innocents is more of a mall, that is, a space reserved for strolling. Built in 1860 during construction of the nearby Halles, this square owes its name to the Cemetery and Church of the Innocents destroyed at the end of the XVIIIth century. The square was lined with lime trees bordering the Fontaine des Innocents, a Renaissance masterpiece by Pierre Lescot and Jean Goujon. Davioud had the fountain moved from its initial location on the Rue Saint-Denis and placed in the middle of the Square des Innocents, atop a stairway of surrounding pools. The tactic is remarkable – instead of drowning the monument in greenery, the architect chose to set it off in a sparse, open space punctuated by the regularity of the tree-lined border.

Incorrectly dubbed a garden square, the Place des Innocents is more of a mall, that is, a space reserved for strolling. Built in 1860 during construction of the nearby Halles, this square owes its name to the Cemetery and Church of the Innocents destroyed at the end of the XVIIIth century. The square was lined with lime trees bordering the Fontaine des Innocents, a Renaissance masterpiece by Pierre Lescot and Jean Goujon. Davioud had the fountain moved from its initial location on the Rue Saint-Denis and placed in the middle of the Square des Innocents, atop a stairway of surrounding pools. The tactic is remarkable – instead of drowning the monument in greenery, the architect chose to set it off in a sparse, open space punctuated by the regularity of the tree-lined border.Square de la Tour Saint-Jacques – 7162 square yards (6016 square metres)

This square, first to be opened to the public in 1856, is the only one whose genuinely square layout merits its title. Strategically located at the crossroads of Paris, the square was born of the major urban construction that turned the neighbourhood upside down during the Second Empire – from the inauguration of the Place du Châtelet to the extension of the Rue de Rivoli and the creation of the Boulevard de Sébastopol. During the Queen Victoria’s visit to Paris for the 1855 World Fair, Haussmann gave her a guided tour of the construction site, proudly displaying the first Parisian square directly inspired by an English model. Like a precious box surrounding the Tour Saint-Jacques – the only remaining vestige of the church of the same name, destroyed in 1797 – the square marks the place that was once the rallying spot for pilgrims headed for Compostella. The Tower was restored by the architect Ballu over the period 1854 to 1858, and a statue by Cavelier portraying Pascal was erected under the keystone to pay tribute to the philosopher who carried out barometric experiments there in 1648.

This square, first to be opened to the public in 1856, is the only one whose genuinely square layout merits its title. Strategically located at the crossroads of Paris, the square was born of the major urban construction that turned the neighbourhood upside down during the Second Empire – from the inauguration of the Place du Châtelet to the extension of the Rue de Rivoli and the creation of the Boulevard de Sébastopol. During the Queen Victoria’s visit to Paris for the 1855 World Fair, Haussmann gave her a guided tour of the construction site, proudly displaying the first Parisian square directly inspired by an English model. Like a precious box surrounding the Tour Saint-Jacques – the only remaining vestige of the church of the same name, destroyed in 1797 – the square marks the place that was once the rallying spot for pilgrims headed for Compostella. The Tower was restored by the architect Ballu over the period 1854 to 1858, and a statue by Cavelier portraying Pascal was erected under the keystone to pay tribute to the philosopher who carried out barometric experiments there in 1648.Square Paul Langevin – 5152 square yards (4328 square metres)

Built in 1868, this square is guarded by a high wall that supports the buildings of the old and prestigious Ecole Polytechnique engineering school. Originally dubbed “Square Monge” after the renowned mathematician who taught at Polytechnique, the square was renamed in honour of the physicist Paul Langevin. A monumental staircase overflowing with viburnum plants creates a mesmerising, tumbling green sculpture.

Built in 1868, this square is guarded by a high wall that supports the buildings of the old and prestigious Ecole Polytechnique engineering school. Originally dubbed “Square Monge” after the renowned mathematician who taught at Polytechnique, the square was renamed in honour of the physicist Paul Langevin. A monumental staircase overflowing with viburnum plants creates a mesmerising, tumbling green sculpture.Square de l’Observatoire:

Jardin Robert-Cavelier-de-la-Salle – 2.8 acres (1.12 hectares)

Jardin Robert-Cavelier-de-la-Salle – 2.8 acres (1.12 hectares)

and [Jardin Marco-Polo] – 2.7 acres (1.09 hectares)These two gardens were created in 1867 between the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Observatory. Their location covers part of the old Vauvert castle which was said to be haunted by the devil. The expression “aller au diable Vauvert” grew out of visitors’ dread of this isolated spot in the garden and thus came to be used for situations in which one found himself in “the middle of nowhere”. Each of the two gardens is planted with four rows of majestic chestnut trees, pruned into a green canopy, and both are decorated with flower beds surrounding statues by the most famous sculptors of the Second Empire: La Nuit (Night) by Gumery and Le Crépuscule (Dusk) by Crauk in the Jardin Cavelier-de-la-Salle; Le Jour (Day) by Perraud and L’Aurore (Dawn) by Jouffroy in the Jardin Marco-Polo. The garden’s outstanding perspective culminates in the celebrated Fontaine des Quatre Parties du Monde. This collective work portraying the four continents was sculpted in bronze under Davioud’s supervision, and is especially noteworthy for the upper section erected by the master sculptor Carpeaux.

Square Boucicaut – 8574 square yards (7202 square metres)

Built in 1870 and inaugurated in 1873, the square owes its name to Aristide Boucicaut, the pioneer of the Bon Marché department store that inspired Zola’s Le Bonheur des Dames. It is located on the site that once housed the former leper-house of the Saint-Germain-des-Près Abbey.

Square Samuel Rousseau – 2078 square yards (1746 square metres)

Built across from the Basilique Sainte-Clotilde in 1857, the Square Samuel Rousseau was, like many squares, designed to glorify the neighbouring monument. Planted on what was once the Dames de Bellechasse Convent courtyard, the square is a particularly calm spot in the heart of Paris.

Built across from the Basilique Sainte-Clotilde in 1857, the Square Samuel Rousseau was, like many squares, designed to glorify the neighbouring monument. Planted on what was once the Dames de Bellechasse Convent courtyard, the square is a particularly calm spot in the heart of Paris.Square Santiago du Chili – 4220 square yards (3545 square metres) and Square d’Ajaccio – 5324 square yards (4472 square metres)

These two squares flank the Hôtel des Invalides on either side. They were planted in 1865.

These two squares flank the Hôtel des Invalides on either side. They were planted in 1865.Square Louis XVI – 4981 square yards (4184 square metres)

Planted in 1865, a year after the Boulevard Haussmann was built, this square sits on what was once the Madeleine cemetery where Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette were buried after being executed. During the Restoration period, Louis XVIII had the couple’s relics moved to the Basilique de Saint-Denis and commissioned Fontaine, Napoleon I’s favourite architect, to erect a memorial known as the Chapelle Expiatoire. The square harmoniously surrounds the monument and offers shade with its magnificent clusters of trees.

Planted in 1865, a year after the Boulevard Haussmann was built, this square sits on what was once the Madeleine cemetery where Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette were buried after being executed. During the Restoration period, Louis XVIII had the couple’s relics moved to the Basilique de Saint-Denis and commissioned Fontaine, Napoleon I’s favourite architect, to erect a memorial known as the Chapelle Expiatoire. The square harmoniously surrounds the monument and offers shade with its magnificent clusters of trees.Square Marcel Pagnol – 4481 square yards (3764 square metres)

Created in 1867 and formerly known as the Square Laborde, the Square Marcel Pagnol is located next to the Eglise Saint-Augustin which was begun in 1860 by Baltard. Much of the site was renovated and re-laid with paving stones laid in 1969.

Created in 1867 and formerly known as the Square Laborde, the Square Marcel Pagnol is located next to the Eglise Saint-Augustin which was begun in 1860 by Baltard. Much of the site was renovated and re-laid with paving stones laid in 1969.Square des Batignolles – 4 acres (1.66 hectares)

Like the Square du Temple, this green space is an exception to the rule as far as squares designed by Alphand are concerned. Planted as an English landscape garden in 1862, the Square des Batignolles differs from others in its large dimensions and its remarkable layout including a waterfall, a river, a lake and rare trees. However the square did not receive unanimous acclaim when it was inaugurated. Unlike in England, the spirit of the day in France was less interested in lawn games and more preoccupied with lawn maintenance. Lush green spaces were thus forbidden to visitors and ornamental ponds were built, considerably reducing room for strolling and play. Despite its beauty, the Square des Batignolles soon proved to be poorly adapted to the surrounding working-class neighbourhood. Luckily, children are now allowed to play on the lawns. Also noteworthy are several Oriental plane trees dating back to the square’s creation.

Like the Square du Temple, this green space is an exception to the rule as far as squares designed by Alphand are concerned. Planted as an English landscape garden in 1862, the Square des Batignolles differs from others in its large dimensions and its remarkable layout including a waterfall, a river, a lake and rare trees. However the square did not receive unanimous acclaim when it was inaugurated. Unlike in England, the spirit of the day in France was less interested in lawn games and more preoccupied with lawn maintenance. Lush green spaces were thus forbidden to visitors and ornamental ponds were built, considerably reducing room for strolling and play. Despite its beauty, the Square des Batignolles soon proved to be poorly adapted to the surrounding working-class neighbourhood. Luckily, children are now allowed to play on the lawns. Also noteworthy are several Oriental plane trees dating back to the square’s creation.Square Berlioz – 1068 square yards (897 square metres)

Formerly known as the Square de Vintimille, it was created in 1859 and completely renovated in 1990-1991.

Square de la Trinité – 3767 square yards (3164 square metres)

Among the drastic changes made in the neighbourhood during the Second Empire, the Square de la Trinité and the church of the same name were designed as a viewpoint and the culmination of perspective lines leading up from the Chaussée-d’Antin. Planted in 1865, the oval-shaped haven was furnished with a fountain by Ballu, the architect who built the adjacent church. The design is based on the number three, mirroring the trinity honoured by both the church and square. Ballu’s three triple-basin fountains are thus situated along the same axis as the three bays of the church vestibule. Above the fountains there are three groups of sculpture by Duret portraying Faith, Hope and Charity. The garden too is structured around three lawns.

Among the drastic changes made in the neighbourhood during the Second Empire, the Square de la Trinité and the church of the same name were designed as a viewpoint and the culmination of perspective lines leading up from the Chaussée-d’Antin. Planted in 1865, the oval-shaped haven was furnished with a fountain by Ballu, the architect who built the adjacent church. The design is based on the number three, mirroring the trinity honoured by both the church and square. Ballu’s three triple-basin fountains are thus situated along the same axis as the three bays of the church vestibule. Above the fountains there are three groups of sculpture by Duret portraying Faith, Hope and Charity. The garden too is structured around three lawns.Square Montholon – 5178 square yards (4350 square metres)

Built in 1863, this square is bordered by four streets which also bear witness to the heritage of Haussmann’s newly-designed Paris. Rue Mayran, Rue Rochambeau and the Rue Pierre Semard were created in 1862 while the section of the Rue Lafayette running along the front of the square was inaugurated in 1859. The Rue Lafayette was subsequently extended to intersect with the Chaussée-d’Antin in 1862. Battered by the weather and construction work for an underground parking lot, the Square Montholon was completely rebuilt in 1971. All that remains of the original square are the wrought-iron gates and two enormous Oriental plane trees over one hundred years old.

Built in 1863, this square is bordered by four streets which also bear witness to the heritage of Haussmann’s newly-designed Paris. Rue Mayran, Rue Rochambeau and the Rue Pierre Semard were created in 1862 while the section of the Rue Lafayette running along the front of the square was inaugurated in 1859. The Rue Lafayette was subsequently extended to intersect with the Chaussée-d’Antin in 1862. Battered by the weather and construction work for an underground parking lot, the Square Montholon was completely rebuilt in 1971. All that remains of the original square are the wrought-iron gates and two enormous Oriental plane trees over one hundred years old.Square Saint-Vincent-de-Paul – 2357 square yards (1980 square metres)

This pretty square at the foot of the Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Church was inaugurated in 1867. Laid out on a steep slope in the period 1824-44, the square provides a lovely setting for the large stairway (built by Lepère and Hittorff) which leads up to the church.

This pretty square at the foot of the Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Church was inaugurated in 1867. Laid out on a steep slope in the period 1824-44, the square provides a lovely setting for the large stairway (built by Lepère and Hittorff) which leads up to the church.Square de la Chapelle – 1694 square yards (1423 square metres)

Located just east of the Place de la Chapelle, this square was created in 1862. Remodelled in 1986, it was named after Louise de Marillac who worked closely with Saint Vincent de Paul.

Square monseigneur Maillet – 3625 square yards (3045 square metres)

This square was built in 1863 adjacent to the Place des Fêtes, a site where the festivities of the Belleville Commune were held. The village feel of the neighbourhood was completely destroyed in the early 1970’s and the square was redesigned in 1971. It was recently renovated and is now a pleasant refuge from the harsh neighbouring urban landscape.

This square was built in 1863 adjacent to the Place des Fêtes, a site where the festivities of the Belleville Commune were held. The village feel of the neighbourhood was completely destroyed in the early 1970’s and the square was redesigned in 1971. It was recently renovated and is now a pleasant refuge from the harsh neighbouring urban landscape.Square Ferdinand Brunot – 4693 square yards (3942 square metres)

This square was erected in 1862 on land that was once the town of Montrouge, facing the 14th arrondissement’s City Hall built by the architect Naissant from 1852 to 1855.

Square Lamartine – 1920 square yards (1613 square metres)

Inaugurated in 1862 this square was named after the poet Lamartine who lived nearby.

-

Route : Gardens

Jardin des Tuileries et du Carrousel – 70 acres (28 hectares)

Located between the Place de la Concorde and the Louvre, the Jardin des Tuileries and the Jardin du Carrousel date back to the construction of the Tuileries palace for Catherine de Médicis in 1564. A century later Le Nôtre elaborated on the layout to create a perfect example of the French formal garden. The Jardin des Tuileries was a public strolling spot for XVIIIth century high society and remained open to the public through the XIXth century, while the area closest to the palace, soon renamed the Jardin du Carrousel, became part of the sovereign’s residence. Under the Second Empire, this garden was redesigned in the English style for the private use of Napoleon III and the imperial family. With the destruction of the Tuileries palace during the Commune, these gardens became public once again. For the publicly accessible Jardin des Tuileries, Napoleon III retained the pre-existing classical layout and built the Jeu de Paume (réal tennis court) for the imperial prince’s recreation. The site later became an exhibition hall for housing impressionist collections, and it is now devoted to contemporary art.

Jardin du Luxembourg – 56 acres (22.45 hectares)

The gardens were planted adjacent to the Luxembourg Palace built by Marie de Médicis in the early XVIIth century. They were later inherited by Gaston d’Orléans, Louis XIII’s brother, who opened them to the public. After many difficulties the palace gardens were confiscated by the Count of Provence. During the French Revolution they were turned into a prison, then subsequently served as the seat of government for the Directory before finally becoming the Senate gardens during the Empire. The Second Empire brought about the greatest upheaval. A decree dated November 28, 1865 ordered the destruction of one-third of the gardens. Twenty-five acres (10 hectares) of “wilderness” were to be destroyed despite public outcry including a petition bearing 10,000 signatures.

The gardens were planted adjacent to the Luxembourg Palace built by Marie de Médicis in the early XVIIth century. They were later inherited by Gaston d’Orléans, Louis XIII’s brother, who opened them to the public. After many difficulties the palace gardens were confiscated by the Count of Provence. During the French Revolution they were turned into a prison, then subsequently served as the seat of government for the Directory before finally becoming the Senate gardens during the Empire. The Second Empire brought about the greatest upheaval. A decree dated November 28, 1865 ordered the destruction of one-third of the gardens. Twenty-five acres (10 hectares) of “wilderness” were to be destroyed despite public outcry including a petition bearing 10,000 signatures. On February 18, 1866 Napoleon III visited the gardens and approved the plans to supplant 30 acres (12 hectares) including the distinguished Pépinière des Chartreux tree nursery. Classical order thus replaced the gardens’ romantic demeanour and the Jardin du Luxembourg found its permanent home within the perimeters we still know today. Davioud built his famous wrought-iron gates, the grounds near the Observatory were divided into squares and the gardens were ornamented with numerous statues – nearly eighty of which are still in the present-day gardens. The Fontaine Médicis was decorated in 1864 with sculptures by Ottin portraying Polyphemus and a grouping of Acis and Galatea. In 1866, the empire-period Fontaine du Regard by Gisors was attached to the back of the Fontaine Médicis, after being removed from its initial spot when the Rue de Rennes was built. Though the Jardin du Luxembourg may have been the only sour note sounded by the Second Empire’s urban planners, it remains today one of the capital’s liveliest gardens.

On February 18, 1866 Napoleon III visited the gardens and approved the plans to supplant 30 acres (12 hectares) including the distinguished Pépinière des Chartreux tree nursery. Classical order thus replaced the gardens’ romantic demeanour and the Jardin du Luxembourg found its permanent home within the perimeters we still know today. Davioud built his famous wrought-iron gates, the grounds near the Observatory were divided into squares and the gardens were ornamented with numerous statues – nearly eighty of which are still in the present-day gardens. The Fontaine Médicis was decorated in 1864 with sculptures by Ottin portraying Polyphemus and a grouping of Acis and Galatea. In 1866, the empire-period Fontaine du Regard by Gisors was attached to the back of the Fontaine Médicis, after being removed from its initial spot when the Rue de Rennes was built. Though the Jardin du Luxembourg may have been the only sour note sounded by the Second Empire’s urban planners, it remains today one of the capital’s liveliest gardens.Jardin Marco-Polo – 2.7 acres (1.09 hectares)

These two gardens were created in 1867 between the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Observatory. Their location covers part of the old Vauvert castle which was said to be haunted by the devil. The expression “aller au diable Vauvert” grew out of visitors’ dread of this isolated spot in the garden and thus came to be used for situations in which one found himself in “the middle of nowhere”. Each of the two gardens is planted with four rows of majestic chestnut trees, pruned into a green canopy, and both are decorated with flower beds surrounding statues by the most famous sculptors of the Second Empire: La Nuit (Night) by Gumery and Le Crépuscule (Dusk) by Crauk in the Jardin Cavelier-de-la-Salle; Le Jour (Day) by Perraud and L’Aurore (Dawn) by Jouffroy in the Jardin Marco-Polo. The garden’s outstanding perspective culminates in the celebrated Fontaine des Quatre Parties du Monde. This collective work portraying the four continents was sculpted in bronze under Davioud’s supervision, and is especially noteworthy for the upper section erected by the master sculptor Carpeaux.

These two gardens were created in 1867 between the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Observatory. Their location covers part of the old Vauvert castle which was said to be haunted by the devil. The expression “aller au diable Vauvert” grew out of visitors’ dread of this isolated spot in the garden and thus came to be used for situations in which one found himself in “the middle of nowhere”. Each of the two gardens is planted with four rows of majestic chestnut trees, pruned into a green canopy, and both are decorated with flower beds surrounding statues by the most famous sculptors of the Second Empire: La Nuit (Night) by Gumery and Le Crépuscule (Dusk) by Crauk in the Jardin Cavelier-de-la-Salle; Le Jour (Day) by Perraud and L’Aurore (Dawn) by Jouffroy in the Jardin Marco-Polo. The garden’s outstanding perspective culminates in the celebrated Fontaine des Quatre Parties du Monde. This collective work portraying the four continents was sculpted in bronze under Davioud’s supervision, and is especially noteworthy for the upper section erected by the master sculptor Carpeaux.

Jardins des Champs-Elysées – 34 acres (13.7 hectares)

This promenade designed by Le Nôtre in the XVIIth century became national property in 1792. To mark this, the Chevaux de Marly (the ‘Marly Horses’), the work of Guillaume Coustou and commissioned by Louis XIV, were placed at the Place Concorde entrance to the gardens on pedestals designed by David. Allied troops camping on the Champs-Elysées from March, 1814 to March, 1816 left the site in a state of total ruin. Under the Second Empire the gardens became very fashionable with an array of cafés, restaurants and theatres. In 1858 Alphand transformed the Jardins des Champs-Elysées into English-style landscape gardens, complete with undulating lawns, flower baskets and clusters of rare trees and bushes that adorn this enduring landscape still today, over one hundred years later. Before the Petit Palais and the Grand Palais were built for the 1900 World Fair, the site housed the Palais de l’Industrie, a huge metal structure which hailed from the first French World Fair in 1855. The building housed major art shows throughout the rest of the Second Empire, notably the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Davioud’s Théâtre du Rond-Point (formerly the Palais des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors)) was inaugurated in 1860. The Théâtre Marigny is the work of Charles Garnier.

This promenade designed by Le Nôtre in the XVIIth century became national property in 1792. To mark this, the Chevaux de Marly (the ‘Marly Horses’), the work of Guillaume Coustou and commissioned by Louis XIV, were placed at the Place Concorde entrance to the gardens on pedestals designed by David. Allied troops camping on the Champs-Elysées from March, 1814 to March, 1816 left the site in a state of total ruin. Under the Second Empire the gardens became very fashionable with an array of cafés, restaurants and theatres. In 1858 Alphand transformed the Jardins des Champs-Elysées into English-style landscape gardens, complete with undulating lawns, flower baskets and clusters of rare trees and bushes that adorn this enduring landscape still today, over one hundred years later. Before the Petit Palais and the Grand Palais were built for the 1900 World Fair, the site housed the Palais de l’Industrie, a huge metal structure which hailed from the first French World Fair in 1855. The building housed major art shows throughout the rest of the Second Empire, notably the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Davioud’s Théâtre du Rond-Point (formerly the Palais des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors)) was inaugurated in 1860. The Théâtre Marigny is the work of Charles Garnier.

Jardins de l’avenue Foch – 17 acres (6.62 hectares)

To connect Paris and the newly created Bois de Boulogne, Napoleon III designed a majestic highway befitting the elegance of the capital’s western neighbourhoods. Avenue Foch, formerly known as Avenue de l’Impératrice, thus came into existence. Legally approved in 1864 and inaugurated in 1865, the Avenue de l’Impératrice was to fulfil its architects’ vision of the world’s most beautiful avenue. Every possible means was used to meet this goal. The Avenue was nearly a mile long and over 450 feet wide, leaving ample room for a broad road suitable for coaches, two side alleys – one reserved for those on horseback and the other for pedestrians – as well as two additional side paths and sidewalks lining adjacent houses. Alphand was entrusted with landscaping this “imperial route”, which he adorned with gardens flourishing with nearly 4000 divers kinds of trees and bushes acclimatised to Parisian conditions. Remarkable examples still lend shade to the present-day Avenue, including several trees over one hundred years old: three plane trees, a horse chestnut tree, a Japanese Sophora, a Siberian elm and a Virginia tulip tree. As early as 1855, before trees were planted or were barely in bloom, with roads still under construction and foundations just being laid, the Avenue de l’Impératrice became a fashionable meeting place for the aristocracy and the demi-monde, where elegant horsemen and gleaming teams of horses with imposing demeanour vied for attention on their way to the Bois de Boulogne.

To connect Paris and the newly created Bois de Boulogne, Napoleon III designed a majestic highway befitting the elegance of the capital’s western neighbourhoods. Avenue Foch, formerly known as Avenue de l’Impératrice, thus came into existence. Legally approved in 1864 and inaugurated in 1865, the Avenue de l’Impératrice was to fulfil its architects’ vision of the world’s most beautiful avenue. Every possible means was used to meet this goal. The Avenue was nearly a mile long and over 450 feet wide, leaving ample room for a broad road suitable for coaches, two side alleys – one reserved for those on horseback and the other for pedestrians – as well as two additional side paths and sidewalks lining adjacent houses. Alphand was entrusted with landscaping this “imperial route”, which he adorned with gardens flourishing with nearly 4000 divers kinds of trees and bushes acclimatised to Parisian conditions. Remarkable examples still lend shade to the present-day Avenue, including several trees over one hundred years old: three plane trees, a horse chestnut tree, a Japanese Sophora, a Siberian elm and a Virginia tulip tree. As early as 1855, before trees were planted or were barely in bloom, with roads still under construction and foundations just being laid, the Avenue de l’Impératrice became a fashionable meeting place for the aristocracy and the demi-monde, where elegant horsemen and gleaming teams of horses with imposing demeanour vied for attention on their way to the Bois de Boulogne. -

Route : Parks

Parc Monceau

On this site purchased by the Duke of Chartres in 1789, Carmontelle planted a “garden of dreams” . A green haven, it was later redesigned in the English style by the landscape gardener Blaikie. During Napoleon’s reign, the Emperor’s interest in the site grew and he considered giving it new life as a zoological park or even a private garden for the King of Rome. It was during the Second Empire that the spot came to resemble the present-day Parc Monceau. In 1860, upon completion of the newly-built Boulevard Malesherbes, the city of Paris acquired 50 acres (20 hectares) of the old park through a compulsory purchase order. Pereire bought half of that land for eight million francs and launched a vast real estate project, while Haussmann and his team of landscapers turned the other half into gardens. Inaugurated on August 13, 1861 by Napoleon III, the park met with immediate success owing to its masterful beauty as well as the surrounding housing estates, since the successful bourgeoisie of the imperial period chose to build their mansions here on the Monceau plateau. Houses built adjacent to the park had to follow certain rules outlined by Haussmann: 15 metres of greenery were required in front of the property as well as gates marking the barrier between public and private space.

Davioud designed the wrought-iron gates with the neighbourhood’s new wealth in mind, and of all the gates built for Parisian parks and gardens during the Second Empire, these are the most magnificent. The whole park was gracefully restructured by to Alphand who used his favourite visual devices, such as rocks, waterfalls, small footbridges over streams, ornamental ponds, and winding paths, to create the illusion of a harmonious landscape. Ledoux built the rotunda known as the Pavillon de Chartres, which served as a toll house until it was restored by Davioud and made into a pavilion for park attendants. Davioud also preserved the “fabriques,” decorative elements typical of XVIIIth century landscape art which were scattered throughout the previous park, the Duke of Chartres’ folly. Their charm still pervades this Parisian haven, as demonstrated by the Naumachie, a colonnade that was initially part of Henri II’s unfinished tomb in Saint-Denis. The Parc Monceau houses the capital’s biggest tree: an Oriental plane tree which measures seven metres in diameter at one metre from the ground.

Davioud designed the wrought-iron gates with the neighbourhood’s new wealth in mind, and of all the gates built for Parisian parks and gardens during the Second Empire, these are the most magnificent. The whole park was gracefully restructured by to Alphand who used his favourite visual devices, such as rocks, waterfalls, small footbridges over streams, ornamental ponds, and winding paths, to create the illusion of a harmonious landscape. Ledoux built the rotunda known as the Pavillon de Chartres, which served as a toll house until it was restored by Davioud and made into a pavilion for park attendants. Davioud also preserved the “fabriques,” decorative elements typical of XVIIIth century landscape art which were scattered throughout the previous park, the Duke of Chartres’ folly. Their charm still pervades this Parisian haven, as demonstrated by the Naumachie, a colonnade that was initially part of Henri II’s unfinished tomb in Saint-Denis. The Parc Monceau houses the capital’s biggest tree: an Oriental plane tree which measures seven metres in diameter at one metre from the ground.Parc Montsouris – 39 acres (15.5 hectares)

An 1865 imperial decree announced the creation of the Parc Montsouris, both to counterbalance the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont erected in the north and to provide open space for people living in the southern neighbourhoods of the capital. Begun in 1867, the park was not completed until 1878 due to delays caused by the war in 1870. The allotted land proved exceedingly difficult to divide into sections due to the passage of two railway lines. Yet Alphand succeeded in transforming the uneven ground adjacent to the Thiers fortifications into a genuine English landscape garden. The architect planted three extensive lawns with bushes and added small paths crossing the lawns to create a trapezoidal garden. The north-eastern tip of the park includes an ornamental pond with thriving aquatic fauna.

An 1865 imperial decree announced the creation of the Parc Montsouris, both to counterbalance the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont erected in the north and to provide open space for people living in the southern neighbourhoods of the capital. Begun in 1867, the park was not completed until 1878 due to delays caused by the war in 1870. The allotted land proved exceedingly difficult to divide into sections due to the passage of two railway lines. Yet Alphand succeeded in transforming the uneven ground adjacent to the Thiers fortifications into a genuine English landscape garden. The architect planted three extensive lawns with bushes and added small paths crossing the lawns to create a trapezoidal garden. The north-eastern tip of the park includes an ornamental pond with thriving aquatic fauna. Three bridges connect the various areas and the railways are hidden by tree-laden ravines. Individual trees attract visitors’ admiration such as a Virginia poplar (north entrance), a Lebanese cedar (north of the lake) and an American sequoia (west of the meteorological weather station). Aside from sculptures made after the Second Empire, the park boasts a monument over fifteen feet high – used as a measuring landmark by the observatory – which was completed by Vaudoyer in 1806. The Bardo, a replica of the bey of Tunis’ summer palace, was placed in the park after being displayed at the 1867 World Fair. A meteorological service was established in 1869 in a fragile but beautiful wooden building, but this unfortunately burned down in 1991.

Three bridges connect the various areas and the railways are hidden by tree-laden ravines. Individual trees attract visitors’ admiration such as a Virginia poplar (north entrance), a Lebanese cedar (north of the lake) and an American sequoia (west of the meteorological weather station). Aside from sculptures made after the Second Empire, the park boasts a monument over fifteen feet high – used as a measuring landmark by the observatory – which was completed by Vaudoyer in 1806. The Bardo, a replica of the bey of Tunis’ summer palace, was placed in the park after being displayed at the 1867 World Fair. A meteorological service was established in 1869 in a fragile but beautiful wooden building, but this unfortunately burned down in 1991.Parc du Ranelagh – 15 acres (6 hectares)

Laid out by Haussmann, the park was opened in 1860 on a site known as La Pelouse (The Lawn). This elegant meeting place hosted the Ranelagh Ball, whose guests included Lucien Bonaparte, Barras, Tallien and the lovely Juliette Récamier. The park faces the Marmottan Museum, a museum housing works acquired by a passionate art collector of the First Empire.

Parc des Buttes-chaumont

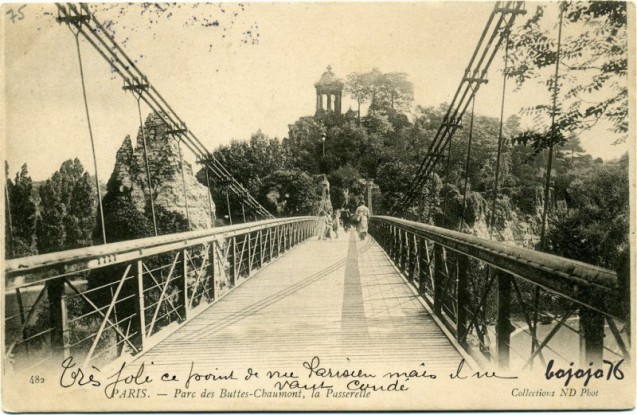

Before becoming a limestone quarry in the XVIIIth century, the Buttes-Chaumont was for four centuries a hated place, home to the Montfaucon gallows . In 1814 the Buttes-Chaumont were the scene of violent conflicts between French and Allied troops, and during the Restoration it became a garbage dump for surrounding neighbourhoods, with a knackers yard and sewage dumps arriving soon afterwards. So it would be an understatement to say the Buttes-Chaumont were not really destined to become a haven of greenery! Yet Haussmann and Alphand decided to convert the Buttes-Chaumont into a park for those living in the northern reaches of Paris – no small feat considering the soil was primarily clay and thus inhospitable to any form of vegetation. In 1860 Napoleon III planned to offer this huge garden to the inhabitants of the newly-annexed communes of Belleville and La Villette. Three years of work were necessary, from 1864 to 1867, to create the extraordinary landscape still there today.

Before becoming a limestone quarry in the XVIIIth century, the Buttes-Chaumont was for four centuries a hated place, home to the Montfaucon gallows . In 1814 the Buttes-Chaumont were the scene of violent conflicts between French and Allied troops, and during the Restoration it became a garbage dump for surrounding neighbourhoods, with a knackers yard and sewage dumps arriving soon afterwards. So it would be an understatement to say the Buttes-Chaumont were not really destined to become a haven of greenery! Yet Haussmann and Alphand decided to convert the Buttes-Chaumont into a park for those living in the northern reaches of Paris – no small feat considering the soil was primarily clay and thus inhospitable to any form of vegetation. In 1860 Napoleon III planned to offer this huge garden to the inhabitants of the newly-annexed communes of Belleville and La Villette. Three years of work were necessary, from 1864 to 1867, to create the extraordinary landscape still there today. To build the park, the site had to be excavated, terraces had to be built with imported soil, and three miles of road had to be laid all this before the planting and designing could begin. To this day the park boasts the following marvels: a 92 foot tall hill of jutting rocks, formed from the quarry excavations, overlooking a five-acre lake; a rotunda built on the rocky summit as a temple of love called the “Temple de la Sybille”, reminiscent of Davioud’s Tivoli Rotunda; a grotto and waterfall with water pumped in from the Saint-Martin Canal; two bridges including the “Suspension Bridge” and the “Suicide Bridge”; eight pavilions for park attendants; restaurants; a bandstand… The park was inaugurated and received a warm welcome amidst the general enthusiasm of the 1867 World Fair. Today this wondrous park remains the Second Empire’s greatest urban planning success story.

To build the park, the site had to be excavated, terraces had to be built with imported soil, and three miles of road had to be laid all this before the planting and designing could begin. To this day the park boasts the following marvels: a 92 foot tall hill of jutting rocks, formed from the quarry excavations, overlooking a five-acre lake; a rotunda built on the rocky summit as a temple of love called the “Temple de la Sybille”, reminiscent of Davioud’s Tivoli Rotunda; a grotto and waterfall with water pumped in from the Saint-Martin Canal; two bridges including the “Suspension Bridge” and the “Suicide Bridge”; eight pavilions for park attendants; restaurants; a bandstand… The park was inaugurated and received a warm welcome amidst the general enthusiasm of the 1867 World Fair. Today this wondrous park remains the Second Empire’s greatest urban planning success story. -

Route : Bois

Bois de Vincennes – 2488 acres (995 hectares)

Once the hunting grounds for a long line of French royalty, the Bois de Vincennes is famous for having sheltered Saint Louis who, as the legend goes, dispensed justice under one of the oaks in the woods. Philippe VI and then Charles V built the Château de Vincennes, which was later changed from a military stronghold to a noble residence by Louis XIV. During the Revolution the estate was made national property. Napoleon I converted the castle into an arsenal in 1808 and had the eight towers along the castle wall torn down, leaving only that known as the “Village Tower”. In 1857 Napoleon III entrusted Alphand with a vast development and renovation scheme. The shooting ranges and drill grounds requested by the Emperor for the military fortress proved particularly problematic since they were to be erected in the middle of the woods. Alphand retained the overall axes but transformed the lawns and empty spaces into an English landscape garden by connecting them with winding paths.

He dug and laid out three consecutive lakes: the Lac des Minimes with three islands, the Lac de Gravelle and the Lac de Saint-Mandé. In 1860 a senatus consultum gave 2335 acres (934 hectares) of the forest to the City of Paris along with the charge of pursuing construction projects. The Butte de Gravelle and the Lac de Daumesnil with the islands of Bercy and Reuilly were thus created and the Paris horticulture school, the Arboretum de Breuil, was founded in 1867. The Zoological Park and the Parc Floral, both built more recently, are today’s most visited sites in the Bois de Vincennes.

He dug and laid out three consecutive lakes: the Lac des Minimes with three islands, the Lac de Gravelle and the Lac de Saint-Mandé. In 1860 a senatus consultum gave 2335 acres (934 hectares) of the forest to the City of Paris along with the charge of pursuing construction projects. The Butte de Gravelle and the Lac de Daumesnil with the islands of Bercy and Reuilly were thus created and the Paris horticulture school, the Arboretum de Breuil, was founded in 1867. The Zoological Park and the Parc Floral, both built more recently, are today’s most visited sites in the Bois de Vincennes.Bois de Boulogne ( 845 hectares)

The Bois de Boulogne is the last surviving vestige of the immense Rouvray Forest where Isabelle de France, Saint Louis’ sister, retired to found the Longchamp Abbey. A mill of the same name is all that remains of the abbey. XIVth century pilgrims returning from Boulogne-sur-Mer received permission to build a church in what was to become the Bois de Boulogne – thus accounting for the name Louis XI gave to the site. During the XVIth century François I erected the Château de Madrid – now no longer standing. In the XVIIth century Longchamp came to be considered a stylish place for a walk, and in the XVIIIth century impressive mansions sprang up there, notably the Château de la Muette and the Château de Neuilly, as well as the Saint-James Folly and the Bagatelle. During the Revolution the wooded park was almost entirely destroyed.

The Bois de Boulogne is the last surviving vestige of the immense Rouvray Forest where Isabelle de France, Saint Louis’ sister, retired to found the Longchamp Abbey. A mill of the same name is all that remains of the abbey. XIVth century pilgrims returning from Boulogne-sur-Mer received permission to build a church in what was to become the Bois de Boulogne – thus accounting for the name Louis XI gave to the site. During the XVIth century François I erected the Château de Madrid – now no longer standing. In the XVIIth century Longchamp came to be considered a stylish place for a walk, and in the XVIIIth century impressive mansions sprang up there, notably the Château de la Muette and the Château de Neuilly, as well as the Saint-James Folly and the Bagatelle. During the Revolution the wooded park was almost entirely destroyed. Thanks to Bonaparte the Bois de Boulogne was revived: the park was cleaned and reforested, and long alleys were created. However, Allied troops camping there in 1814 and 1815 left the site a wasteland. In 1848 the Bois became state property and in 1852 Napoleon III handed it over to the City of Paris, on the condition that a promenade open to the public be built and maintained. The Emperor hoped to create a Parisian version of London’s Hyde Park. Landscape architects laid out winding paths, created the Lac Supérieur and the Lac Inférieur with two connected islands, designed the Grande Cascade waterfall using rocks from Fontainebleau and, thanks to impressive hydraulic work, fashioned three rivers and planted 400,000 trees along with countless clusters of flowers. In addition, the Longchamp Hippodrome was built to host horse races and plots of land were granted for various ventures such as the Jardin d’Acclimatation children’s park and the self-contained park known as the Pré Catelan. Napoleon III closely supervised these projects, seeing in them the perfect fulfillment of his ideas and designs for green spaces in the capital.

Thanks to Bonaparte the Bois de Boulogne was revived: the park was cleaned and reforested, and long alleys were created. However, Allied troops camping there in 1814 and 1815 left the site a wasteland. In 1848 the Bois became state property and in 1852 Napoleon III handed it over to the City of Paris, on the condition that a promenade open to the public be built and maintained. The Emperor hoped to create a Parisian version of London’s Hyde Park. Landscape architects laid out winding paths, created the Lac Supérieur and the Lac Inférieur with two connected islands, designed the Grande Cascade waterfall using rocks from Fontainebleau and, thanks to impressive hydraulic work, fashioned three rivers and planted 400,000 trees along with countless clusters of flowers. In addition, the Longchamp Hippodrome was built to host horse races and plots of land were granted for various ventures such as the Jardin d’Acclimatation children’s park and the self-contained park known as the Pré Catelan. Napoleon III closely supervised these projects, seeing in them the perfect fulfillment of his ideas and designs for green spaces in the capital. In 1857 he commissioned Davioud to erect the Kiosque de l’Empereur, a small pavilion at the southern tip of the Lac Inférieur reserved for his personal use. Restored exactly according to the original plans in 1985, this charming pavilion is a perfect example of imperial society’s love affair with the Bois de Boulogne. The park’s success was such that the Bois soon became the requisite strolling grounds of the Second Empire’s social elite, the stage on which every afternoon they showed themselves off to the world.

In 1857 he commissioned Davioud to erect the Kiosque de l’Empereur, a small pavilion at the southern tip of the Lac Inférieur reserved for his personal use. Restored exactly according to the original plans in 1985, this charming pavilion is a perfect example of imperial society’s love affair with the Bois de Boulogne. The park’s success was such that the Bois soon became the requisite strolling grounds of the Second Empire’s social elite, the stage on which every afternoon they showed themselves off to the world. -

Continuations

“Of all the urban improvements made in Paris during the Second Empire, none deserves greater praise, more genuine admiration, than the work of the Promenades and Plantations Office in Paris… From the quarry it was at the time, Paris was turned into a bouquet of flowers.” This assessment by César Daly, which appeared in the 1863 Revue de l’Architecture bears witness, despite its slight exaggeration, to the warm welcome reserved for the parks and gardens created upon the Emperor’s request. Though the destruction of “old Paris” and the work that turned the city into one huge construction site prompted indignation and protest at first, the quick completion of several projects silenced the most hostile opponents. Within only a few months, for example, Parisians developed a true passion for the Bois de Boulogne. Visitors flocked to savour ice cream at the Chalet des Iles, to go rowing and explore flora and fauna along the banks, and to admire the small-scale model of an ocean-going boat, La Ville de Nantes, presented just a short while earlier at the 1855 World Fair and anchored from then on in the middle of the Lac Supérieur.

Walks which had once been a Sunday affair soon extended to the whole week. People came to see and be seen at the Bois, especially since this trend had been set in motion by the imperial couple. Visitors could often catch a glimpse of the Empress on horseback, surrounded by her lady companions as she galloped at full speed down the wide alleys of the Bois. On other days the Emperor would be seen driving his own phaeton, racing through the woods accompanied by two attendants seated behind him. The Bois de Boulogne quickly won acclaim and became the privileged setting for high society’s afternoon strolls, theatre or opera, and fashionable dining into the evening. The Goncourts, always so “pleasant” with regards to their contemporaries, cynically summed up this new-found delight: “Just think! We could be rid of a great deal of chic foolishness and elegant stupidity were a bomb to kill, one fine day, all those Parisians having their four to six o’clock stroll around the lake in the Bois de Boulogne.” Fascinated by the affluent visitors, Paris’ lower classes soon made their way to the Bois to spy on the Sunday parade. Members of “polite society” gradually grew uneasy about keeping such “lowly company” and ceased their Sunday pilgrimages to the alleys of the Bois, reserving such walks for other days of the week.

One of the elite’s most prized pastimes was ice skating. Napoleon III, who learned to skate as a child in Augsburg and Arenenberg, had Alphand design a shallow lake near the Jardin d’Acclimatation for this purpose. The Empress was also at ease on the ice and the imperial

couple often held sumptuous gatherings on the small frozen lake. A trend was born! During the winter Parisians tried the new sport and while the sight, still rare, of a graceful ice skater won bystanders’ admiration, the rest of the crowd kept to their sleds and sleighs.The Pré Catelan and the Jardin d’Acclimatation were noteworthy attractions in their own right in the Bois de Boulogne. By paying one entrance fee, the elegant visitor could wander among an Italian marionette theatre or a magic show, a reading room or a dairy, a concert hall, an open-air theatre and a photographer’s studio. Once the novelty wore off, the Pré Catelan attracted fewer and fewer people and finally closed its doors in 1861. On the other hand, the Jardin d’Acclimatation with its zoological gardens was so successful that is still there today. A passion for horse-racing, nurtured mostly by the Duke of Morny, ultimately found its home at the Hippodrome de Longchamp racecourse, where all of Paris flocked to be part of the electric ambience of the Grand Prix, so memorably described by Zola in his novel Nana.

These forms of entertainment all catered to the wealthy. In northern and eastern Paris people began visiting parks and gardens more and more. Entire families took the train or the slower omnibus to spend the day in the Bois de Vincennes, eating lunch on the grass and taking Sunday boat rides on the lake. The great woods were deserted the rest of the week since the stylish crowds snubbed Vincennes for western Paris and the Bois de Boulogne. The Buttes-Chaumont faced the same dilemma: the working class could only go on their day off and what’s more, despite the grandiose landscape, the park was located in a neighborhood far too disreputable for more bourgeois visitors. The squares and large gardens in the centre of Paris hosted a more mixed crowd. Groups of merchants and students, and the lower and middle class quickly grew fond of the squares built for them and came simply to relax, listen to concerts or let their children play. On the whole, not much has changed since then.

-

Curiosity corner

The history of Parisian gardens is closely tied to the monarchy and the religious congregations of the period. When royal power came to rule Paris under the Capetians, a considerable wave of construction swept through the capital. The garden as part of the estate appeared at this time when land was divided up into lots. Religious communities like Saint-Martin-des-Champs, Saint-Germain-des-Près, Sainte-Geneviève and Saint-Victoire also played an important role in establishing plots where plants were grown.

In the XVth century, gardens were enclosed plots divided into rectangles. Above all, they were private, of moderate size, and hidden behind the shelter of high walls or fences. A garden was first and foremost a functional space: the vegetation grown fulfilled the adjacent estate’s food needs or provided medicinal plants. Yet such utilitarianism did not preclude elegant flower compositions and cloister gardens often adorned with fountains; the garden was well on the way to becoming a place of reflection and meditation.

By the end of the Middle Ages, and especially under the influence of the Crusaders who brought back new notions of the garden from the Orient, a distinction grew between pleasure gardens and functional gardens. Exotic animals became a common garden sight; the garden was becoming picturesque. Mechanical devices of the Renaissance turned gardens into places for amusement, an approach brought to full fruition in the XIXth century when green spaces became more and more popular.

From the XVIth century on, the development of private noble architecture considerably enriched the capital’s stock of parks and gardens. During the same period, Parisians took to strolling near the city walls which, little by little, as their military functions declined, became places for relaxing amidst flourishing theatres, cafés, gardens, shady bowers and cottages. The planting of the Jardin des Tuileries was a first step in extending the capital beyond the city walls. This movement, begun by parks, played a notable role in Paris’ westward urban development.

The art of the French formal garden reached its pinnacle in the XVIIth century. While XVIth century spaces were simply treated as sequential plots, a remnant of the medieval period’s square garden enclosures, the XVIIth garden became a vast landscape with vegetation creating perspective. Flights of fancy, especially grottoes, were used to set off the geometric exactness. The most famous grotto designer, Bernard Palissy, worked for Le Nôtre at the restructured Tuileries gardens. But on the whole, Parisian gardens went ignored next to the ostentatious royal flowerbeds of Versailles.

For XVIIIth century gardens, ‘fantasie’ or flight of fancy became the important feature. Whilst XVIIth century gardens had called for a wide perspective to see and appreciate the mastery of the overall composition, XVIIIth century gardens emphasized the element of surprise. All along their strolls, visitors came upon small monuments, Chinese temples, colonnades, sheep pens and fountains, all expressive of a new fondness for ruins set in recreated natural landscapes.

The garden as a display of power made way for the garden as a miniature replica of the world. All the features of natural surroundings were reproduced: valleys, hills, rivers, paths. Follies were de rigueur in gardens of the period. The Saint-James Folly in Neuilly and a few others in the Parc de Bagatelle and the Parc Monceau are still standing, although they have undergone considerable modification.Gardens such as those in the Palais-Royal were opened to the public, the Palais-Royal gardens becoming a favourite promenade among Parisians of the Enlightenment. Religious congregations also began welcoming visitors to their gardens, the most famous of these gardens being the Chartreux Orchard at the Observatory.

During the French Revolution, aristocrats’ private gardens were vandalized, looted, divided up and sold. Fortunately the Empire repaired the damage. Napoleon made a general plan for the gardens of the capital where green spaces made powerful statements creating sweeping vistas. Such projects included the culmination of the Champs-Elysées with the Arc de Triomphe, the renovation of the Tuileries and the impressive design to develop the Chaillot hill.

The Restoration brought the interesting contributions of Prefect Rambuteau, who proved to be the pioneer of gardens intended for public use. The first public garden for local use was planted at the foot of Notre-Dame. Reshaped by Alphand, this garden is now known as the Square de l’Archevêché.

It was the Second Empire which established a real strategy for landscape development in Paris. For both philanthropic and health reasons, Napoleon III outlined projects for four major parks at the cardinal points of the capital: the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and the Parc de Montsouris respectively to the north and south, and the Bois de Vincennes and the Bois de Boulogne to the east and west. Moreover, he planned for a whole array of small local designed to offer a moment of relaxation for both working-class and bourgeois visitors. Countless intersections and avenues were also created and lined with plane and chestnut trees. These were in fact Baron Haussmann’s favorite trees and he happily planted them everywhere, much to the chagrin of the civil engineers who saw them as a threat to their macadam roads! Major projects included the Place Malesherbes, the Place de Grenelle, the Avenue de l’Observatoire and the Avenue du Président Wilson (called the Avenue de l’Empereur at the time), the Boulevard Richard Lenoir, and the list goes on… The architect Davioud was responsible for designing all the urban furniture, much of which still graces the city’s landscape today: benches, bins, pavilions and bandstands, fountains, lampposts, poster boards and signposts, fences and balustrades, jetties, diverse shelters, restaurants and park attendant pavilions. Aside from the relatively common chestnut and plane trees, gardeners planted sophoras, lime trees, maples, acacias, cedars, poplars, ash and black pines, and also bushes with year-round foliage such as aucubas, spindle-trees, box trees and laurels. Flowerbeds bloomed with rare blossoms like geraniums, begonias, dahlias and petunias which adapted so well to the climate they have become commonplace today.

After the war in 1870 this approach to landscaping received little attention, although the underlying principles had become engrained in people’s minds. For over one hundred years housing developments took priority over parks and gardens, especially when the last fortifications were levelled. After World War II Parisian gardens went more or less overlooked, until the early 1970s when the City of Paris launched a campaign to create parks and gardens in the vein of the Imperial design and new sites were born: the Parc Georges Brassens, the Parc de Belleville, the Jardin des Halles, the Parc de Bercy, the Parc André Citroën, the Daumesnil or Reuilly-Bastille tree-lined paths, the Jardin Atlantique over the Gare Montparnasse train station and the renovation of the Tuileries as part of the Palais du Louvre construction project.

Add to that long list a multitude of small local squares and all the historic gardens still in existence, the Jardin du Palais-Royal, the Jardin des Plantes, the Jardin du Champ-de-Mars, the Jardin du Trocadéro, the Arènes de Lutèce and Musée de Cluny gardens, and Paris literally seems to overflow with impressive and incredibly lush vegetation.

-

Bibliography

Here are a few books we recommend on Parisian gardens:

ALPHAND Adolphe, Les promenades de Paris, 2 volumes. Paris: Rothschild, 1867-1873; reprint Princeton Architectural Press, 1984.

This volume bears witness to the crucial role played by the outstanding engineer Alphand in creating urban park projects. Illustrated with numerous period drafts, engravings, drawings of park furniture, etc.ALPHAND, ERNOUF, l’art des Jardins, Paris: 1868.

A fascinating essay revealing the ideas about, and methods used in, gardens of the mid-XIXth century.BAROZZI Jacques, Guide des 400 jardins de Paris: Hachette, 1982.

A must! The most comprehensive and practical guide for anyone interested in uncovering all of Paris’ natural treasures.CABAUD Michel, Paris et les Parisiens sous le Second Empire, Pierre Belfond, 1982.

A wonderful panorama of Parisian life with period photographs showing the parks and gardens featured in our itinerary at the time they were planted. Fascinating.CHOAY Françoise, “Haussmann et le système des espaces verts parisiens”, Revue de l’Art, (no. 29, 1975, pp. 83-99).

An article analyzing Baron Haussmann’s exact role in the design and realization of the Second Empire’s gardens.Paris-Haussmann “le pari d’Haussmann”, Paris: Pavillon de l’Arsenal, Picard, 1991.

An wonderful volume which looks at parks and gardens of the Second Empire in the context of the period’s overall urban planning strategies.Parcs et promenades de Paris, Paris: Pavillon de l’Arsenal, 1989.

An exhibition catalogue presenting an excellent study of the topic enhanced by interesting illustrations.DUBOIS Philippe J. and Guilhem Lesaffre. Guide de la nature à Paris et en banlieue, Paris: Parigramme, 1994.

Few illustrations other than a several black and white drawings, but a practical little guide, nonetheless, for exploring today’s flora and fauna.MALET Henri, Le baron Haussmann et la rénovation de Paris, Paris: Les Editions municipales, 1973.

MANEGLIER Hervé, Paris Impérial. La vie quotidienne sous le second Empire, Armand Colin, 1990.

Discover the entertainments and activities in the gardens of the Second Empire.Several beautiful volumes noteworthy for their photographic reproductions.

QUEFFELEC Henri, Paris des jardins, Photographs by Hervé Boulé, Editions ouest France, 1988.

Jardins de Paris, Texts by J.J. Lévêque, Hachette, 1982.

JOUDIOU G. and P. Wittmer, Cent jardins à Paris et en Ile de France, Délégation à l’action artistique de la ville de Paris, 1992.

LE DANTEC Denise and J.P. , Splendeur des jardins de Paris, Photographs by C. Baker, Flammarion, 1991.

-

Practical information

Park Hours

The capital’s squares and gardens are open every day throughout the year from 7am to 9:30pm in the summer, and from 9am to 8 or 9pm in the winter. Many parks close at sundown during the winter season.

– Jardin des Tuileries: 7:30am – 7:30pm in the winter; 7am – 9pm in the summer

– Parc Monceau: 7am – 8pm (Nov. 1 to March 31); 7am – 10pm (April 1 to Oct. 31)

– Parc Montsouris: 7am – 8pm (Nov. 1 to March 31); 7am – 9pm (April 1 to Oct. 31), 24 hours a day from 1 July to 3 September

– Parc des Buttes-Chaumont: 7am – 9pm (Nov. 1 to March 31); 7am – 10pm (April 1 to Oct. 31) 24 hours a day from 1 July to 3 SeptemberUp-to-date opening times of all Parisian parks and gardens can be found here. Updated 2017)

Addresses

Jardins des Tuileries et du Carrousel – Main Entrances: Place de la Concorde or Place du Carrousel 75001 Paris

Metro: Tuileries or ConcordeSquare Louvois, rue de Richelieu, rue Rameau, rue de Louvois 75002 Paris

Metro: Quatre – SeptembreSquare Emile-Chautemps, boulevard de Sébastopol, rue Saint-Martin, rue Papin 75003 Paris

Metro: Réaumur – SébastopolSquare du Temple, rue du Temple 75003 Paris

Metro: Temple or Arts et MétiersSquare des Innocents, place Joachim du Bellay, rue des Innocents 75001 Paris

Metro: Châtelet – les HallesSquare de la Tour Saint-Jacques, boulevard de Sébastopol, avenue Victoria, rue de Rivoli 75003 Paris

Metro : ChâteletSquare Paul Langevin, rue Monge, rue des Ecoles 75005 Paris

Metro: Cardinal LemoineJardin du Luxembourg, boulevard Saint-Michel, rue de Vaugirard, rue Guynemer, rue Auguste-Comte, rue de Médicis 75006 Paris

RER : LuxembourgSquare de l’Observatoire, avenue de l’Observatoire 75006 Paris

RER: Luxembourg or Port-RoyalSquare Boucicaut, rue de Babylone, rue Velpeau, boulevard Raspail 75007 Paris

Metro: Sèvres – BabyloneSquare Samuel Rousseau, rue de Martignac, rue Casimir Perrier 75007 Paris

Metro: SolférinoSquare d’Ajaccio, boulevard des Invalides, rue de Grenelle 75007 Paris

Metro: VarennesSquare Santiago du Chili, avenue de la Motte-Picquet, boulevard de la Tour-Maubourg 75007 Paris

Metro: La Tour – MaubourgJardins des Champs-Elysées, avenue des Champs-Elysées, Cours la Reine, avenue Franklin-D-Roosevelt, avenue Matignon, avenue Gabriel 75008 Paris

Metro: Champs-Elysées-Clémenceau or ConcordeSquare Louis XVI, boulevard Haussmann, rue des Mathurins 75008 Paris

Metro: Saint-Augustin or Saint-LazareSquare Marcel Pagnol, place Henri Bergson 75008 Paris

Metro: Saint-AugustinParc Monceau, boulevard de Courcelles 75008 Paris

Metro: MonceauSquare des Batignolles, place Charles Fillion 75017 Paris

Metro: BrochantSquare Berlioz, place Adolphe Max 75009 Paris

Metro: Place de ClichySquare de la Trinité, place d’Estienne-d’Orves 75009 Paris

Metro: TrinitéSquare Montholon, rue Rochambeau, rue Pierre Semard, rue Lafayette, rue Mayran 75009 Paris

Metro: PoissonnièreSquare Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, place Franz Liszt 75010 Paris

Metro: PoissonnièreSquare de la Chapelle, place de la Chapelle 75018 Paris

Metro: La ChapelleParc des Buttes-Chaumont, avenue Simon Bolivar, rue de Crimée 75019 Paris

Metro: Buttes-Chaumont or BotzarisSquare Monseigneur Maillet, place des Fêtes 75019 Paris

Metro: Place des fêtesBois de Vincennes, avenue de Daumesnil, avenue de Gravelles 75012 Paris

Metro: Porte Dorée or Château de VincennesParc Montsouris, 2 rue Gazan 75014 Paris

Metro: Cité UniversitaireSquare Ferdinand Brunot, place Ferdinand Brunot 75014 Paris

Metro: Mouton-DuvernetSquare Lamartine, avenue Victor Hugo, avenue Henri Martin 75016 Paris

Metro: Rue de la PompeParc du Ranelagh, avenue du Ranelagh, avenue Ingrès 75016 Paris

Metro: La MuetteJardins de l’avenue Foch, avenue Foch 75016 Paris

Metro: Porte Dauphine or Charles-de-Gaulle-EtoileBois de Boulogne, Porte Maillot, Porte Dauphine, Porte d’Auteuil 75016 Paris

Metro: Porte Maillot, Porte Dauphine or Porte d’AuteuilActivities

In all Parisian squares, gardens and parks you will find areas reserved for children with playgrounds, sandboxes, see-saws, swings, and all sorts of merry-go-rounds. Some spaces offer a wider range of activities: toy boats to sail, sulky and go-cart rentals in the Jardin du Luxembourg; ping-pong tables in the Square Emile-Chautemps and the Jardin de l’Observatoire; pony or carriage rides at Parc Monceau and the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont; tennis courts, boules, réal (royal) tennis and croquet at the Jardin du Luxembourg; Guignol marionette puppet shows at the Jardin du Ranelagh, the Jardin des Champs-Elysées, the Tuileries, the Jardin du Luxembourg, Parc Montsouris and the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont; roller skating at Parc Monceau, Parc Montsouris, the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and the Square de l’Observatoire; a bee-keeping school at the Jardin du Luxembourg; bandstands featuring spring and summer concerts at the Square du Temple, the Jardin du Luxembourg, Parc Montsouris and the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont.

These open spaces also beckon visitors just to wander and daydream, and many offer lush green lawns for sitting or taking a rest. Just make sure to watch for signs posted on lawns that are accessible to the public: “pelouses autorisées” and “pelouses au repos”.

The Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes offer a wide range of activities with something for everyone, from botany to cultural and athletic pursuits.

Bois de Vincennes

Botany:

- The Nature Path (Sentier Nature) takes you on an hour-and-a-half stroll, with sixteen waymarkers conveniently placed to allow you to discover the park’s fauna and flora. The walk starts along the banks of Lac Daumesnil, at the Carrefour de la Conservation. A guide is available from the Tourist Information Office in Vincennes.

Tel: 01 48 08 13 00 - The Parc Floral de Paris is located across from the Château de Vincennes on the Esplanade.

Tel: 01 49 57 25 50 (Maison du Jardin Botanique)

Tel: 01 49 57 24 81 (Espace Jeux du Parc Floral)

This 75 acre (30 hectare) park hosts an impressive collection of camelias, bulbs and perennial flowers. Not to be missed are the sweet aromas of the Jardin des Senteurs and the pine grove planted with rhododendrons and shady plants. - Arboretum of the Ecole de Breuil, Rue de la Ferme.

A living museum comprised of more than 1200 trees, representing 800 different species over 13 hectares. A map of the arboretum can be found here.

Culture:

- Théâtre du Soleil-Cartoucherie, Bois de Vincennes

Tel: 01 43 74 87 63

An independant theatre with a varied programme of productions. - Marionette puppet shows at the Théâtre des Marionnettes, 5 Avenue du Belair (behind the City Hall in St. Mandé, next to the Châlet du Lac).

Tel: 06 75 23 45 89 - Théâtre Astral, Productions for children in the Parc Floral.

- La Grande Pagode, Route de la Ceinture, Bois de Vincennes, 75012.

This Pagoda serves as the seat for the ‘Union Bouddhiste de France’, and also houses the largest Buddha in Europe. It is only open to the public on certain Buddhist festivals, a calender of which can be found here. - National Museum of the History of Immigration (Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration). A museum examining the effect which immigrants have had upon French history, and the role they have played in the economic, cultural and social development of France.

Sports:

- Centre Equestre Bayard UCPA, (Horse riding) Bois de Vincennes-Avenue du Polygone

Tel: 01 43 65 46 87 - Horse riding at the Centre Equestre de la Cartoucherie, Bois de Vincennes