The Napoleonic Museum in Cuba is the happy result of the combination

of the personal collections of Julio Lobo and Orestes Ferrara.

The artefacts and memorabilia on exhibition were bought at auction

during the first half of the 20th century and represent the most

important Napoleonic collection in Central America. The collection

itself was declared a 'National Heritage' in 1960 and, with the

revolutionary government's blessing, the museum was opened to

the public in the following year.

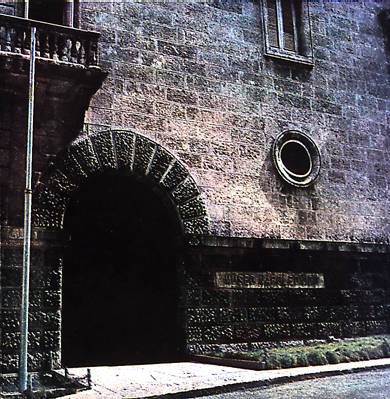

The exhibits are housed in Orestes Ferrara's residence, the

Villa Fiorentina, a beautiful and vast Renaissance-style palazzo

built in the 1920's. The objects on show (which in 1986 were valued

at 8 million dollars) include arms, militaria, furniture, bronzes,

porcelain, paintings, sculptures, coins, personal items belonging

to Napoleon and his entourage, books, engravings and autograph

letters. More than 7000 pieces go to make up this extraordinary

museum.

The structure of the museum mirrors the main political and military

events of the Napoleonic saga. Thus a visitor sees first the fall

of the monarchy, goes next to the rise of Napoleon and his taking

of power, and then is presented with an evocation of the wealth

of the empire before beginning the descent, from the abdication,

to the exile on Elba, the Hundred Days, Waterloo and the demise

on St Helena.

All along the route of the visit works by the great artists of the

period crowd the walls. There are pictures by Gérard, the official

portrait painter to the court and especially the imperial family,

notably portraits of Caroline Bonaparte and Hortense de Beauharnais.

There are paintings of Napoleon, Elisa and Pauline by Robert Lefevre.

Gros is also represented by two portraits, one of general Marceau

and another of Napoleon in Italy, as is Andrea Appiani with his

canvass showing Napoleon in Milan, and Jean-Baptiste Regnault with

his monumental Napoleon at the camp in Boulogne. There are in addition

works by lesser-known artists such as Marguerite Gérard, the sister-in-law

and pupil of Fragonard, with her double portrait of Jérôme Bonaparte

and Catherine de Wurstemberg. Indeed, paintings by such late 19th-century

artists as Bellangé, Vibert, Meissonier and Detaille testify to the

enduring popularity of the Napoleonic saga as a subject for a work of

art.

Sculpture is equally well represented with busts of Pauline by Romagnesi,

of Josephine by Chinard and of Matilde by Bartolini. Furniture and

objets d'art fill the rooms, with the works by such famous names

as Jacob Desmalter and Thomire. Of particular note is Thomire's

magnificent eighteen-branched chandelier designed by Percier which

belonged to Josephine and which was used at the house in the rue

des Victoires and at Malmaison. Indeed, this wide-ranging collection

of furniture gives a good impression of what a upper-class villa in

the first quarter of the 19th century actually looked like. Glass

cases containing Napoleonic costumes, arms and militaria complete

the picture.

One of the most eye-catching pieces is however Napoleon's death mask.

This is a bronze cast (one in a limited series) made in 1833 from

the original taken by the doctor Antommarchi on St Helena. In fact,

François Antommarchi travelled to Cuba in 1837 to study yellow fever,

and died there on the 4th April 1838, his body being buried in the

Sainte-Iphigénie cemetery in Santigo de Cuba. The Napoleonic Museum

in Cuba also has a very rich library (of over 5000 volumes) open to

both students and researchers.

Museo Napoleonico – Cuba