Situated in the Latin quarter close to Notre-Dame cathedral, the Museum of Public Health and the Hospitals of Paris (Musée de l'Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris) has been sited in the Hôtel de Miramion, a building attributed to François Mansart, since its creation. This private town mansion was, as early as 1674, associated with the history of public health and hospitals in Paris when it was the house for a community of Filles de Sainte-Geneviève, sisters dedicated to helping the poor. In 1812, it became the Pharmacie Central des Hôpitaux.

The museum itself was founded in 1934, and it is the only museum in Paris on the history of hospices and hospitals from the Middle Ages to the present day. The collection comprises more than 5,000 objects and is the result of a policy of the preservation of hospital utensils, the purchasing of items and donations and bequests.

The museum opens with a historical overview. It recounts the foundation of the hospital as a result of the church's policy of Christian charity as shown through the hospitaller sites. The Hôtel-Dieu (the Paris hospital opposite Notre-Dame) dates originally back to the middle of the 7th century, and it was founded by the bishop of Paris, St Landry. In the wake of the crusades, many religious orders set up hospitals or hospices, but it was not until the 18th century that populations (and consequently minimum health requirements) grew and with them came new hospitals. In Paris there were the Cochin and Saint-Jacques hospitals founded in 1780, closely followed by the Beaujon-Necker foundation, a supplement to Louis XIV's Hôpital général of 1670. The museum continues with a presentation of the administration and daily life of these institutions, as well as details about the lives of the great charitable figures such as Saint Vincent de Paul. A large part of the museum is taken up with the subject of the abandoning of infants. Up until the 19th century, the most common method of getting rid of unwanted children was 'exposure'. In an attempt to deal with this, many towns operated a system based on 'exposure towers', whose existence was not recognised officially until an Imperial decree of 1811. These exposure towers were circular constructions with an opening low down. Within the opening there was a rotating board upon which the mother placed her baby. By turning the board, the baby was taken to 'the other side', usually into a hospital or hospice where it was looked after. The museum has a fine example of such a tower which was used in a hospital in Uzès in the Gard region of France. It also possesses some touching examples of objects of recognition (letters and other items) left by the parents. The use of such towers was prohibited in 1861 and a law of 1869 made the Departments responsible for foundlings.

The end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century were rich in public health improvements. The Revolutionary assemblies (and later the Empire) passed numerous bills fixing the status and workings of the hospitals. In 1801 the Conseil général des Hôpitaux et Hospices civils de Paris (the general council for the hospitals and hospices of Paris) was founded, and the three great Ancien Régime establishments, the Hôtel-Dieu, the Hôpital général and the Enfants trouvés (or foundling hospital), were combined. In 1802 and 1803, two decrees fixed the number and roles of the external and internal staff of the hospitals. The reorganisation continued in 1849 with the nomination of a director general for public health, Davenne (1789-1869), as a replacement for the directoral college, prone as it was to internal division.

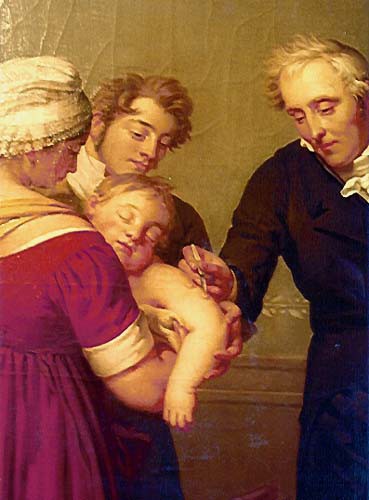

This ethnological and historical collection of hospital history is completed by various items of medical interest, notably: G. Dupuytren's (1777-1835) surgical case, a magnificent box comprising five drawers encrusted with ivory and metal; pharmaceutical objects; paintings (“Vaccine at the Château de Liancourt” by C. Desbordes – see inset); engravings; sculptures (busts of Bichat, Delessert and Dupuytren); manuscipts; medical treatises; and archival documents.

Museum of Public Health and the Hospitals of Paris