On conquering Egypt Just as he had with Malta, Napoleon set about introducing civic structures and generally bringing what he felt were the benefits of the 'enlightenment' to a backward country. As de facto ruler of the land he went to the mosques and called meetings of the Cairo government or Diwan – all this despite a bloody insurrection in the first months of French rule (Cairo, 21-22 October, 1798). Napoleon's first manifesto to the Egyptian was couched in particularly attractive terms:

1) the removal of the Turks from power in Egypt

2) the introduction of Egyptians in positions of political influence regarding internal matters

3) respect for religious traditions

4) better social and economic conditions.

The existing ruling powers

To do this Napoleon had to enlist the help of the ruling elite of Sheikhs, and to encourage them to take positions of power, in order to bring the rest of Egypt with them. As with the sheikhs, Napoleon had also to impress the Copts. The Copts, Christians in the heart of a Moslem society personified the permanent structures of Egyptian bureaucracy. They were the scribes of Ancient Egypt, and in 19th century Egypt they were the accountants. Whether caliph or provincial governor, Emir, Mamluk or Turkish Pasha, no-one could get by without their assistance.

Bonaparte’s approach to religion

Napoleon's conciliatory approach to Islam is well documented. He is known to have admired the Mohammed – he even learned off by heart several suras of the Koran. His relationship with Christianity being one of a practical statesman – religion was useful as long as it was comforting to society, but dangerous if it lead to fanaticism. And his frank disbelief in the Trinity caused him to adopt monotheistic attitude, obviously not a million miles from Islam.

The festivals

Very cunningly Napoleon, steeped in the Revolutionary tradition of fêtes, made significant appearances at three fêtes in Egypt, namely the fête of the Nile (28 August, 1798), the fête or mawlid of the Prophet (anniversary of his birth beginning on 21 August, 1798), and the fête de la République (22 September, 1798).

Very cunningly Napoleon, steeped in the Revolutionary tradition of fêtes, made significant appearances at three fêtes in Egypt, namely the fête of the Nile (28 August, 1798), the fête or mawlid of the Prophet (anniversary of his birth beginning on 21 August, 1798), and the fête de la République (22 September, 1798).

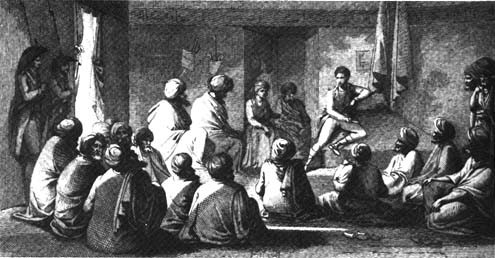

The Nile festival was a pagan event celebrating the Nile floods which brought fertility to the plains. The canals storing the flood waters were opened and the water stored. Napoleon attended the event as spectator but also as benefactor. His appearance at the festival of the prophet was a much riskier business. The Cairo notables seemed that they were not going to keep the festival. Napoleon therefore encouraged them, providing both a place and funding. Cairo celebrated for three days –sufis danced in the streets until they fell over from exhaustion, the French soldiers had fanfares and fireworks. During this time, Bonaparte was the guest of the sheikh Al Bakri. 'In his black uniform, buttoned up to the neck, he made stark contrast with the sheikhs in their ceremonial robes, turbans, nodding to the rhythm of the verses of the Koran and telling their beads' (Herold, J.C., Bonaparte en Egypte, 1962). The republican festival was an attempt to raise troop morale, but also to impress the locals with a show of military might. The ceremonial was prepared in minute detail. Rigo's paintings show a fête of great pomp and luxury – there were horse races, banquets, illuminations and fireworks. And Bonaparte invited 150 guests to a sumptuous dinner. It was a great public relations coup.

The Suez Canal

Napoleon was, we know, interested in the canal in Egypt. In his school notebooks he copied a whole passage from Diodorus Siculus on the canal built by Necho. In his eleventh cahier (Masson, vol 2, p.47) Napoleon noted 'the isthmus of Suez…is only 30 leagues in length and…joins Asia and Africa'. Furthermore, in his sixteenth cahier (Masson, vol. 1, p. 316) 'This canal was 25 toises wide and 50 leagues long. It began in the Delta and there are only slight remains of it left'.

Before leaving Paris for the expedition, the Directory was careful to instruct Bonaparte to have a very close look at the technical conditions required for building another canal.

In November 1798 Napoleon sent General Bon to occupy the town Suez on the Red Sea. He rapidly fortified the emplacement, setting up cannons. On the day before Christmas, Bonaparte reached the isthmus with a large retinue, amongst whom the generals Berthier, Caffarelli, Dommartin, and the Rear Admiral Ganteaume, as well as the members of the Institut d'Egypte Berthollet, Monge, Lepère, Costaz to name but few, and some prominent figures from Cairo. In addition to merchants who joined the convoy to take advantage of the relative safety, there was a guard corps of three hundred. It took him only three days to reach Suez, and on that journey he visited the Moses fountain. On returning on the 30 December, he set out to look for the remains of the previous canal. According to the official version (Le courrier de l'Egypte, no. 24, 27 nivôse, Year VII) 'the caravan headed towards Ajerud. The commander in chief accompanied by other generals and citizen Monge went to the northernmost extremity of the gulf to see if there were remains of the canal which was marked on the map…and such remains were indeed found. General Bonaparte found them first and the troop marched for four leagues in the canal itself'.

Having found the canal, Lepére was soon charged with performing some initial survey work. But this soon to stop owing to a lack of water, danger from attacks by locals and the imminent departure of the expedition to Syria. And it was not until November 1800 that survey work was to restart. Starting in the centre of the canal, the survey party divided into two brigades, one heading for the Mediterranean and the other for Cairo. Villers de Terrage graphically describes the difficulties. 'The work was often disturbed through lack of water. At one point we thought that we were not going to able to complete the project. The difficulties inherent in the harsh climate (notably the necessity of lengthening of the level sightings for lack of water) meant that we had to rush some of the tasks and leave out some of the readings we planned to make'. 'I have already mentioned that all the good instruments which we brought with us from Paris were destroyed in the Cairo revolt.' 'When we finished, we handed over all our notebooks to Lepére who with the help of his brother (Gratien) was to co-ordinate them'.

Unfortunately, because of the inaccuracies engendered, Lepére described the difference in levels as 9.91m. He recommended the building of a second canal, at a cost of 30 million Francs, 10,000 workers and four years. And for fifty years these results were to remain the authority on the subject.

The end result

The Egyptian expedition lasted only three years and three weeks. But despite that brief length of time, scholars and historians agree that this period has two important effects on the future development of Egyptian culture, namely:

the introduction into Egypt of the principle of equality before the law;

the development of Western culture in Egypt.

Bibliography

Arbois, G., 'L'impossible rêve oriental de Napoléon', S.[ouvenir] N.[apoléonien] 402, pp. 26-37

Brégeon, J.-J., L'Egypte française au jour le jour 1798-1801, Perrin, Paris, 1991

Ghali, I.A., 'L'Expedition d'Egypte vue par les auteurs égyptiens', S.N. 291, pp. 2-11

Masson, F. Napoléon inconnu, 2 vols. Ollendorff, Paris, 1895