To discover three paintings telling the story of Napoleon’s second and final exile click here.

From Waterloo to the island of St Helena

On 18 June 1815 Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo in Belgium by the British and Prussian Allied armies. Back in Paris, on 22 June he abdicated in favour of his only son aged four. The latter, who had been in hiding in Austria since May 1814 with his mother the Empress Marie-Louise would never become Emperor. Instead it was Louis XVIII (the brother of Louis XVI who was guillotined during the French Revolution) who would become King of France.

On 25 June Napoleon left Paris. After a short stint to get to Malmaison where he saw his mother for the last time, he arrived on 3 July at Rochefort where he planned to set sail for the United States. The passport promised by the French provisional government was never granted, and so instead Napoleon landed on the small island of Aix, off Rochefort, and put himself in the hands of the British navy which was stationed there, “I have come to put myself under the protection of your prince and your laws”. On board Bellerophon, Napoleon was taken to the port of Torquay. He stayed there a few days, much to the amusement and curiosity of the British who congregated in small boats to get as close as possible in hope of a glimpse of the fallen Emperor, who was only known henceforth as “General Bonaparte”. When he arrived at the port of Plymouth he learned on 31 July that he was to be exiled to St Helena, a small island under British rule in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. On 7 August, Napoleon embarked onto a new ship, Northumberland, and left British waters on 9 August, having never set foot on British soil. After a journey of nine weeks at sea, he arrived at the island of St Helena on 15 October 1815.

Life on St Helena

Twenty people followed Napoleon into exile: The General Bertrand (who had also been Grand Marshal of the palace), with Fanny, his wife, and their three children, General de Montholon with his wife, Albina, and their son; General Gourgaud, and Count Las Cases – the only man who spoke perfect English – and his son. Then there were his servants: his first valet Louis Marchand, Louis Etienne Saint-Denis (known as “Ali Mamluk”); and his butler “a little spy” Cipriani who had known Napoleon since childhood. Despite the restrictions imposed by the British, Napoleon was allowed to take with him some furniture and tableware from the Imperial palaces, as well as paintings and family souvenirs, such as a portrait of his son, who was known as “the King of Rome”.

The day after his arrival, Napoleon moved into a family house known as the Briars. It was home to the Balcombe family and their daughter Betsy, aged 14. Cheerful, lively, Betsy was not intimidated by Napoleon, who appreciated her company and enjoyed talking with the girl.

After a couple of months of building work, the residence known as ‘Longwood’ was finally ready to welcome Napoleon on 10 December 1815. His fellow exiles and domestics also lived there in adjoining buildings, with the exception of the Bertrand family who had an independent house. Longwood is located in the eastern part of the island, which is windswept and with little vegetation. Napoleon often complained about the constant humidity of the island.

The prisoner’s days were organised around meals, horse riding and dictating his memoirs to his companions. The evenings were spent listening to piano music, playing chess or cards. An enthusiastic reader, Napoleon took over 600 books with him, and, as a result of donations and purchases, by the time Napoleon died his library included over 3000 books on all subjects – history, politics, geography, military arts and mathematics, plays, poetry, novels… To break the monotony, Napoleon even tried gardening.

Life on St Helena, for a man who had ruled over an Empire, gradually became depressing. Napoleon was only allowed to walk freely within a limited area and under the supervision of several British soldiers. His house was watched day and night, his letters were opened before he could read them. The governor of the island, Sir Hudson Lowe, was a ruthless jailer, obsessed with the possibility of Napoleon’s escape. After all, he had already escaped from Elba in March 1815, where he had been exiled for the first time in 1814! The island of St Helena was well guarded by three thousand men, and four vessels constantly surveyed its coastline to prevent any landing.

Over the years, Napoleon shut himself away in Longwood, refused visits and spent more and more time alone in his room. He was desperate to have news of his son. Some members of his entourage left the island and returned to Europe: General Gourgaud in 1818 and Madame de Montholon in 1819. In December 1816, Las Cases and his son were evicted from the island for attempting to smuggle letters in secret.

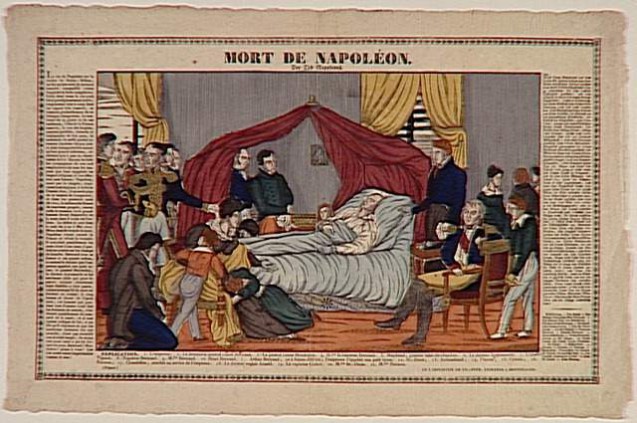

The last days of Napoleon

Napoleon’s health began to cause concern from July 1820. The Emperor hardly ever went out and spent long hours in his bath to soothe his liver pains. According to Antommarchi, his surgeon, he slept more than twelve hours a day and rarely left his bed. He sometimes forced himself to take a walk, but quickly became exhausted. Napoleon died on 5 May 1821 at 5.49pm at the age of fifty-one years. The next day, the governor of the island, Hudson Lowe, visited the deceased in order to certify his death. Then an autopsy was performed by Dr Antommarchi who declared that the death had been caused by a stomach ulcer. On 7 May, a plaster mould was made of Napoleon’s face. On 10 May, Napoleon was buried in a valley close to Longwood, known as Geranium Valley. He was buried under a tombstone without any inscription, because the English refused that the name “Napoleon” could be engraved. On 27 May, the Emperor’s last companions-in-exile left St Helena on a British ship, Camel, and arrived in Europe on 2 August 1821.

In 1840, King Louis-Philippe organised the return of Napoleon’s remains to Paris, which are now buried under the Dome of The Invalides.

Napoleon’s memoirs and the Memorial of St Helena

For many long hours, Napoleon employed Las Cases, the Generals Bertrand, Montholon, and Gourgaud, to write down his memoirs and the stories of his campaigns, as well as explanations of his decisions and actions. On each occasion, after hearing the subject which was to be written about, the “secretaries” used to consult the imposing library, suggest notes to Napoleon who could then dictate. For hours he dictated, corrected, then corrected some more, either in his own room or in the billiard room. After partial publication between 1823 and 1825, the “Memoirs to serve the history of France under Napoleon I” were published in full in 1847, and between 1867 and 1870. They were translated into Spanish, Swedish, Norwegian, German…

Another book which would fascinate the Europeans of the nineteenth century was The Memorial of St Helena written by Las Cases, and translated into eight languages. In it, Las Cases, collected together the thoughts of Napoleon as heard during the many conversations they had shared starting from the boat journey to St Helena until Las Cases left the island in 1816. It also chronicles daily life at St Helena. As an admirer of the Emperor, Las Cases painted a flattering portrait of the prisoner, and particularly emphasised the difficult living conditions imposed upon Napoleon by the governor of the island, Sir Hudson Lowe. Published in 1823, the The Memorial of St Helena can be considered a work of propaganda that would nourish the cult of Napoleon during the nineteenth century. But contrary to what is often claimed, it was not the number one bestseller of the nineteenth century. The actual best-selling book of the nineteenth century was the Fables of La Fontaine! [the equivalent of Aesop’s Fables in the UK]

Both the French and British witnesses who lived with Napoleon on St Helena (Generals Bertrand, Gourgaud, Montholon, Louis Marchand, the Mamluk Ali, Doctors O’Meara and Antommarchi …) left letters sent to their families, as well as stories and memories which give a more or less complete picture of the Imperial exile.

Joanna Benazet and Irène Delage, October 2015 (translation Rebecca Young)