Napoleon’s ‘Grande Armée’ (2)

Uniforms

A soldier’s campaign uniform consisted mainly of breeches or trousers, a shirt and a jacket or short-jacket with epaulettes. Foot-soldiers also wore white, black or grey gaiters which offered protection for their lower legs. A long outer-coat or coat was useful in keeping out the cold and for sleeping in. The clothes were made of woollen cloth, which was warm but not waterproof at all, and would get heavy and cold if it rained. Cuirassiers wore a cuirass, a plate-armour breastplate, which was held together with leather straps, and which protected the wearer from enemy slashes.

Different regiments wore different headgear, allowing individual units to be recognised. Dragoons were easily distinguished by their iron or copper helmets which were topped with a plume. Infantry soldiers simply wore a cap, decorated with a cockade (military rosette or knot of ribbon) in the national colours (red, white and blue).

Aside from their weapons and everything needed to use them (powder, cartridges, bayonette) and look after them, one of the essential items in a soldier’s equipment was his shoes or boots. Marches were often long, and a key element of victory was often the ability to surprise the enemy through superior mobility. Soldiers therefore did not hesitate to take the boots from dead men who had fallen on the battlefield.

Equipment

Each soldier carried a backpack or haversack, which could weight as much as 30kg and which contained his clothes, a blanket, food (bread, meat, wine and ‘grog’) and his tobacco. Meals were served twice a day and soldiers supplemented their reserves by hunting game or requisitioning items from locals (vegetables, meat, eggs, flour etc). Sat around a fire in the evening, or on non-fighting days, some soldiers would play instruments and sing. Others who could read and write would record their day or events in their notebook or write letters home on behalf of their comrades. Some would carve objects out of wood (sometimes even little statuettes of Napoleon!). When on campaign, the soldiers would most often sleep under the stars or under a shelter made of tree branches, or even sometimes in barns. Officers would sleep in tents or in local homes.

On the battlefield

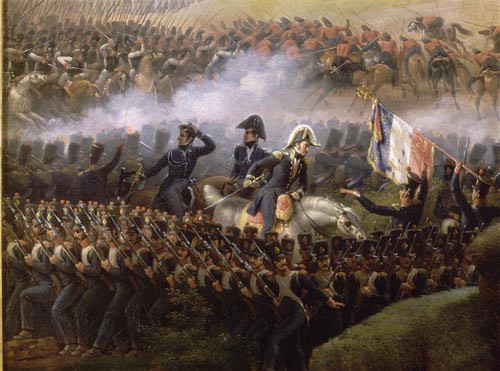

Before a battle, a speech by Napoleon was often read to the soldiers, after which the generals and their aides-de-camp would go back to their respective regiments on the battlefield, based on the orders of the Emperor. During battle, orders were transmitted by musicians, drums and trumpets: rather unfairly, soldiers nicknamed them the ‘loin-des-balles’ (‘far from the bullets’), even though they risked their lives just as much as the standard soldiers.

Based on the terrain and the organisation of the enemy, different units would enter the battle and in different areas. The artillery would be brought in at the point where the enemy appeared the most weak, firing cannonballs of 7 to 12kg. The infantry was given the job of firing continuously, for which a lot of soldiers were needed. They would be organised into three ranks, one behind the other; each rank would take their turn to fire and reload. This was necessary because it took more than a minute to load and fire a rifle. Finally, the cavalery would charge the enemy in order to destabilise it and hopefully rout the opposing soldiers. In the chaos of the battlefield, with canon smoke everywhere, the soldiers could often see nothing more than the back of the soldier in front of them.

The injured were picked up by ‘flying field ambulances’, a system of light vehicles, introduced by the surgeon Dominique Jean Larrey, which could move about easily on the battlefield. Treatment was carried out as quickly as possible, but was often very basic. Most of the time, it involved amputation, and this at a time when general anaesthetics were not yet used. Many injured soldiers died from their wounds, particularly as medicine had not yet advanced enough to prevent infection. Over the various napoleonic campaigns between 1799 and 1815, it is estimated that roughtly 900,000 soldiers lost their lives. In comparison, World War I, which lasted four years, resulted in 1.4 million deaths, although these were partly down to new tactics and equipment such as aerial bombardment and toxic gas attacks, for example.

Illustrations

Top: Napoleon generally wore a simple Imperial Guard grenadier-colonel uniform (portrait by Gérard, Musée de l’île d’Aix © RMN)

Middle: Uniform of a sapper belonging to the Engineer corps: the sapper worked under the orders of engineers, constructing bridges and fortifications (portrait by Delpech, musée de l’Armée de Paris © RMN)

Bottom: Uniform of an Imperial Guard cannoner: the cannoner was given the job of moving the cannons (portrait by Delpech, musée de l’Armée de Paris © RMN)

I. Delage (Sept. 2008, trans. H.D.W.)