Off St. Helena: Friday, 15th August, 1817 Copied by his great-grand-daughter, M.C. Bernard, from the diary of Lieut. Herbert John Clifford, R.N, 1817 [written on board H.M. sloop Lyra on the homeward voyage from China, whither the Lyra had gone with Lord Amherst’s embassy.]

We arrived at St. Helena late in the afternoon of the 11th inst., being five weeks within one day from the Isle of France, and twelve days from rounding the Cape. We sailed again yesterday afternoon, but owing to light winds during the night we were at daylight this morning still in sight of the island, distant about forty miles.

On arriving in the bay of St. Helena we found several men-of-war. The flag of Rear-Admiral Plampin was flying on board the Conqueror, 74, by a boat from which ship we were boarded before we anchored, and both Hall Capt. Basil Hall, R. N. and myself were surprised by a note from Mr. cairns; the first lieutenant of her, who was an old friend and companion of ours on our first going to sea in the Leander in 1802. We had neither of us met for many years; I had not seen him for upwards of ten. The meeting on all sides was agreeable, and I remained the evening with him, while Hall went on shore to wait on the Governor and Admiral.

At dinner I met Sir Thomas Reade, the Adjutant-General; who informed me that Hall would possibly see Napoleon Buonaparte on the following day, after the review which was to take place on account of the Regent’s birthday. Sir Thomas being aware of the difficulty of my hearing in time from Hall for this purpose kindly offered to have a horse in readiness for me in the morning and said he would himself accompany me to the review. Before I proceed further I must in justice to Sir Thomas Reade observe that on all other occasions we found him equally kind and friendly and obliging to a degree which is seldom met with from a stranger. His manners and appearance, which are both genteel and soldierlike, have a very peculiar degree of softness and sweetness, which can only be the effect of a very delightful disposition, aided by a long intercourse with the world and an intimate connection with the best society.

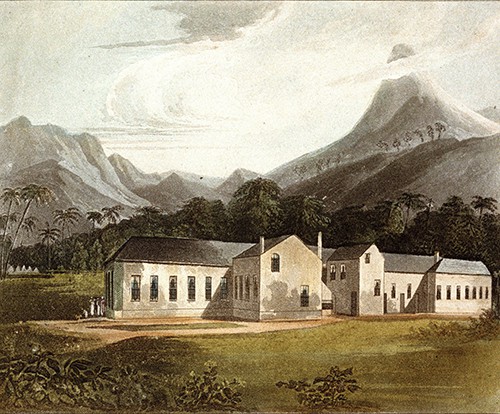

As the review was put off I proceeded to join Hall at Plantation House, the residence of Sir Hudson Lowe, the Governor; it was a distance of about three miles up a winding road over Ladder Hill, the height of which is 597 feet. We met on the road and I learned from him that we were to sail in the evening; that a message had been sent to Marshal Bertrand, at Longwood, to say that Captain Hall wished to pay his respects to Napoleon, and that we were to go over to him about one o’clock.

On my reaching Plantation House I found Captain Hervey had arrived before me; he was with the Governor’s secretary, Major Gorriquer, in a very comfortable library and shortly afterwards we were joined by Sir Hudson and Lady Lowe. I found them both very polite and her ladyship very affable. We remained here till after lunch, and then again mounted our horses and set out for Longwood, which we reached about four o’clock. The road from the quantity of rain which had fallen was very bad, and we crossed several valleys the descent to which was disagreeable, added to which we had several gates to open, which we found it difficult to do without dismounting, although the St. Helena horses are said to be trained to this kind of work.

On our arrival at Longwood, we inquired for Captain Blakeney of the 66th Regiment, the officer in charge of Napoleon; soon afterwards we were introduced to Dr. O’Meara, the surgeon of the Bellerophon, who accompanied the ex-Emperor into his exile. We were conducted by the latter gentleman to Count Bertrand’s residence a few yards below Longwood House; it is a small cottage of one story in height, having a hall and two rooms on the ground floor, besides some alteration which was added to it in front. The house has been built since the party came to the island.

On our entry we were introduced to Count Bertrand, who is rather a plain-looking man and less like a soldier than the generality of field-officers one meets with; he appears, however, a pleasant gentlemanlike man, but there is a crying look about his countenance. He was very polite and requested us to sit down. He conversed with Hall in French, and afterwards spoke to Hervey and me in the same language, but finding that neither of us spoke French he addressed us in bad English. We had sat about a quarter of an hour with him, when the door of an adjoining apartment was opened by the Countess Bertrand, who in very good English requested us to walk in. We were now ushered into a room bearing somewhat more the appearance of comfort than that which we had left, for, although small, it was fitted up in a good style and well furnished, and really had an air of comfort about it. In the former one I was struck on my entry by seeing an infant’s clothes drying on a horse before the fire; this, I could not help thinking, was a sad change for a woman who had been all her life accustomed to the first circles in France.

The Countess, after our introduction by Dr. O’Meara, seated herself on a sofa near the fire, wrapped up in a large shawl, and we soon found that she had been unwell – indeed her swelled face indicated her present suffering. She entertained us, however, in very good style, and sent us away highly pleased with her; from her manners and conversation we all agreed that she is both a ladylike and well-informed woman. She is tall and of a fine figure, and upon the whole of a prepossessing appearance; her age may be about thirty-two. She seemed much entertained by the account of our voyage and took much interest in it. She had an infant in her arms – a fine child – and she told us that she had lost another at Elba, which was poisoned by the French physician, who when drunk administered too large a dose of opium. She has three other children, whom we afterwards saw; the two eldest are boys, but Henri, the youngest, is the finest. The other is a little girl about six or seven years of age – the prettiest creature I ever beheld, her long dark hair fell in flowing ringlets over her shoulders, being parted in front just sufficiently to display a pair of the most beautiful black eyes imaginable, and as she took occasional peeps at us there was an archness in her smile scarcely describable.

We remained here until Dr. O’Meara informed us that we could not be admitted to the presence of the ex-Emperor. We then took leave of the Countess, who afterwards took great interest in our seeing Napoleon, and we owe not a little to her influence over her husband, aided by the efforts of Dr. O’Meara, for our ultimate success. We did not again see the Count; he probably did not like to be the bearer of a disagreeable answer. We were of course much disappointed after having had a very disagreeable ride of eight miles over a bad road amidst rain and dirt, with all the hopes of being received, added to which we had looked forward to this event for a long period of time. The reason assigned by the doctor for our not being received was that Napoleon had just returned from his walk, and having thrown off his coat would not again put it on. This Dr. O’Meara informed me on our arrival he feared would be the case. On Hall consulting with Dr. O’Meara, who it appears had a great interest with Buonaparte, there appeared a gleam of hope that he might be induced to give us an audience the next day; and as Sir Hudson had been requested that the brig might be detained until noon, it was agreed that Dr. O’Meara should make a signal – Yes or No – in the morning. And here we parted, Hall for Plantation House, Hervey and myself for the ball at the Government House in town – where we saw all the beauty and fashion of St. Helena, which does not amount to a very large sum.

With great anxiety did we wait until two o’clock on the following day in hopes of hearing our fate. At length it was announced by Sir Thomas Reade, who instantly ordered horses, and we set out at a full gallop for Longwood, a distance from town of five miles. On our way we passed the Briars, the seat of Mr. Balcombe, which has acquired celebrity from its being the first residence of Buonaparte in the island. We arrived at the Guard-House, near Longwood, at least an hour before Hall, owing to some mistake in the signal. On his arrival we found that there still remained great doubts whether Hervey and I should be able to see the ex-Emperor, whose objection the day before had been to a party; he said if Captain Hall had been alone he would have received him.

We now made up our minds to be refused an interview, and even wished to go away, which Hall objected to, as it had been thought best by Sir Hudson that we should accompany him and take our chance of being admitted. We were now met by Dr. O’Meara, who conducted us all to Marshal Bertrand; he said we could not do better than wait there until Hall was received, and possibly Buonaparte might admit us. We were quite happy to follow his advice, and felt that we should be well recompensed for the trouble of our journey by an hour’s conversation with the Countess Bertrand, for whose inspection we had brought the Loo-choo sketches and costumes, painted by Mr. Havil, the artist to the Embassy.

We were entertained with cake and wine, and shortly after the Count left us habited in the full uniform of a French Marshal. He had not been long gone when a servant came to say that he was waiting to introduce Captain Hall to the Emperor – as also the other gentlemen. This was more than we had anticipated, and certainly it made us very happy to find ourselves so near the object of our wishes and the anxious solicitude of many hours of the last two years. We were received in an ante-chamber by the Count, who conducted Hall into the presence while Hervey and I waited outside. He remained with him about twenty minutes, during which time we heard an occasional laugh which we could scarcely credit; however, we found afterwards that it was true. We were now admitted together, which from Hall’s being received alone we had not anticipated; this was fortunate, for while Hervey was answering his inquiries, I surveyed this wonder of the world from head to foot. Our interview was short. After making a bow, he immediately began questioning Hervey, for whom as well as myself Bertrand interpreted, and in very good English. Seeing Captain Hervey in a military uniform, he asked to what regiment he belonged, and whether foot or horse; he then pointed to a piece of cape on his arm, and said he perceived he was in mourning and requested to know for whom. On being told ‘his father,’ his look suddenly became expressive of concern for his loss, and he repeated the words of his Marshal, ‘son père,’ and the interjection ‘hah’. At this time his countenance appeared to greater advantage than I ever afterwards saw it. He then turned to me, and as I was in plain clothes, instead of asking me the usual naval questions, such as ‘Who have you served with &c.’ he requested to know of what country I was – what part of the country – and how I came to St. Helena, and if I had been all the voyage with Captain Hall. Upon my answering these questions, he bowed us out of the room. Our gratification was complete; we had seen and conversed with Napoleon Buonaparte; and after taking leave of the Countess Bertrand, Dr. O’Meara, and Captain Blakeney, to the former of whom we owed our success, we departed for James Town for the purpose of embarking.

I found Napoleon a very different man in appearance from what I had imagined he was, even shorter and more corpulent than I expected. His hair, which is dark, was cut short all round; his head is very large, and he has a full round face, but not so fat as it is generally represented; his whiskers are shaven off. I saw nothing extraordinary in any of his features except his eye, which is the best feature of his countenance, and seems to give all it expression; but the eyes really did not appear to me to be of that penetrating kind which are generally described. I did not conceive that his full face was at all like the portraits of him, but his profile struck me as being very like, and I think is generally well imitated. There is a sour look about his face which it does not seem an easy matter for him to get rid of. He honoured me with a smile, but it was evident from his manner that he looked upon us as people who came more from his curiosity to look at him than any respect or admiration of his character, or from whom he was likely to obtain much information – which first part was true enough. But by a little condescension on his part he might have purchased our good will. He looked, I thought, very sallow and even ill – but this is said always to be the case. I found no difficulty in looking him full in the face, nor did I find that he possessed that scrutinising glance which is described to belong to his eye. His tout-ensemble had more the appearance of a man devoted to study than the air of one who had devoted his life to military glory. His questions were not so quick as we had been led to expect; indeed, Dr. O’Meara informed us that towards Englishmen he had altered his manner, finding it was not the characteristic of the nation.

He was dressed in an old green coat with covered buttons, a white waistcoat, small clothes, and silk stockings, shoes and buckles, and on his breast he wore an old shabby star. He received us as in his usual mode – standing with his hands in his breeches pockets, and a three-cornered cocked hat under his arm; the tricoloured cockade I did not observe – if any, it must have been hid by his arm. During Hall’s interview with him he asked a variety of questions; these were mostly about his father, whom he had known at the College of Brienne. He said that he recollected him from the circumstance of his having been the first Englishman he ever met. The pictures of Loo-choo seemed to interest him, and one of Sulphur Island (a barren rock) he said exactly resembled St. Helena; he examined minutely all the others, and asked a variety of questions about these Islanders, their customs, manners, religion, laws &co., and seemed much astonished when he found they had no missile weapons, nor firearms. When Hall mentioned that they had no firearms, he said that he supposed he meant they had no cannon; but, upon being assured that they knew nothing of either arms or the use of powder, he seemed greatly surprised that they had no means of doing mischief to their neighbours. He then asked what they knew of Europe, when he told him that they did not know of the existence of such a country. This opportunity was taken of saying that they had not even heard of him, at which he made a great exclamation, and laughed heartily. His other questions to Hall were about the Royal Society of Edinburgh, of which his father is the President; he asked the number of members &c.

It is said that he detests the present Governor; this is probably because he does his duty. But it would be useless to enumerate the evils of which he is said to complain, and of which our stay was too short to form any ideas. I shall, therefore, just relate such anecdotes of him as came within my knowledge.

He has, besides the Count Bertrand, who is styled Grand Marshal of the Palace, two generals – Montholon and Gourgaud. The latter we met as we left Longwood; he is said to be the best of the party. This may arise from his choosing to mix more with the English. He was dressed in plain clothes, and is a gentlemanlike-looking Frenchman. The other General we did not see; his son, a boy of seven or eight years of age; is a nice lad. Green seems to be the favourite colour of these exiles. Las Cases, who was his secretary, is a prisoner at the Cape, having been sent away from the Island on account of the correspondence which was found on a boy, written on silk, and sewed into the lining of his jacket. This is said to have been a trick of Las Cases to get sent off the Island. Buonaparte denies all knowledge of the circumstance, and said as Las Cases was fool enough to get into a scrape, he must get out of it in the best way he could. The Governor it seems had information of the scheme, but would not interrupt it until it became ripe, when he surrounded Las Cases’ room, and seized all the papers, while another party secured the boy. Many curious documents came to light on this occasion, but every paper written in Buonaparte’s hand was returned unread by Sir Hudson Lowe with a polite note, which is said to have been quite satisfactory; those in the handwriting of Las Cases were all detained.

It is said that Buonaparte still keeps up as much of his former pomp as his present circumstances will admit. His Generals never go to him but in full uniform, and when they attend him in his walks are always uncovered. He is styled Emperor by all his household; but the Government do not allow his visitors to do so, and it is always known this be the case.

Mr. Elphinstone, the Chief of the British factory at Canton, sent him not long since a present of a set of superb ivory chessmen and card counters on each of which was an imperial crown over the letter N. The Governor, not expecting this, had sent word of their arrival and promised to send them over as soon as they reached him. Had he known of the imperial crowns before this promise they would not have been sent; but as his word was given he could not retract, and they accordingly sent with an intimation that nothing so marked could in future be sent. In reply he received an impertinent letter from Bertrand (dictated by Buonaparte) saying that he supposed the Emperor’s linen, which happened to be marked with the imperial crown, would be seized when sent out to wash. Sir Hudson is said to have answered Buonaparte with proper temper and spirit on this and several other occasions. On the last time Sir Hudson saw him he was obliged to quit the room on account of Buonaparte’s insulting language; this event took place shortly after Sir Hudson came to the government. Sir Thomas Reade on the following day carried a message to him from the Governor, and intimated before he saw him, that it would be impossible for him to stand the same conduct he had practised to Sir Hudson. Buonaparte is said to have laughed heartily, desired him to be admitted, and talked to him with great coolness and good humour. Sir Thomas described him as a sulky fellow, who is never thankful for any kindness which is shown him, and he says this is also the case with all his followers.

From Captain Blakeney I learned that it was not necessary, as is reported, that he should see Buonaparte every six hours. His orders only direct that he should ascertain the fact of his being present morning and evening prior to a signal being made to the Governor that ‘all is well with respect to General Buonaparte;’ and this ceremony of seeing him is got over by his walking out, or this officer being satisfied that he is in his room, which I should imagine can only be done by having spies among his servants. Captain B. has charge of all the guard which surrounds Longwood in a circuit of four miles, in which range Buonaparte is allowed to go without his attendants; but if he wishes to go out of these bounds Captain B. must be with him. In consequence of this regulation, he never goes out of the bounds, and during the last twelve months he has never mounted a horse. Captain Poppleton of the 53rd Regiment, who has charge of him formerly and to whom he usually applied the epithet of his Gaoler, was sixteen months with him; he never once spoke to him, nor has he yet ever spoken to captain Blakeney. The sentinels draw in at sunset from the circuit close round the house and withdraw again at daylight. I am told the first time he observed these sentinels he was excessively enraged. The story of his having rode away from Captain Poppleton I found was true; in this instance he rode past the outer sentinels (who were punished) and ascended the top of Diana’s peak, the highest in the island, being 2,697 feet, by a road which no one had ever attempted on horseback before. On being asked how he could think of riding in such places, he said, ‘Where a man could go a horse might.’ Had his horse, however, deviated in the slightest degree from the path; he must inevitably have been dashed to pieces; but he was ever a very desperate rider. The alarm was given on this occasion, but on the Captain’s return he found him in his room.

At this period of his captivity he frequently rode out, both on horseback and in his carriage. He frequently took Lady Malcolm out with him; he is said to have been fond of her society on account of her speaking Italian. He is more fond of speaking Italian (which is his native language) than French; he understands English; but cannot pronounce it at all. In his walks he went frequently to visit the cottage of the Adjutant of the 53rd, on which occasions he never failed to poke about every corner and made many inquiries relative to the use of various articles which he met with. This gentleman was a married man. There was also a farmer in the neighbourhood, who had a pretty daughter whom Napoleon made frequent visits to, being a great admirer of the young lady’s beauty; on this lady being married, he requested to see them both, and paid the husband many compliments on his valuable acquisition. Buonaparte is to-day forty-nine years of age; it is said he has only taken medicine three times in his life. He is said, notwithstanding, to entertain a high opinion of the faculty; he cures all his complaints with a warm bath.

The house at Longwood is low and small; but the place itself is, I think, superior in many respects to the Governor’s at Plantation House. The timber for his new house has been reported in readiness to be put up, but he will not give Sir Hudson any answer with respect to his wishes on this head. The room in which we were received is described as a good one, but I candidly confess that I cannot give any opinion of it; my attention was otherwise directed. The other rooms which we saw were small. There is a long billiard room in front of the house, where, it is said, he walks up and down at least three hours of the day, and when the weather is fine he extends his walk as far as the garden when all his staff attend him uncovered. He sometimes pays Madame Bertrand a visit and sits with her for some time. He employs the remainder of the day in reading and writing. It is still supposed that he is writing his life; indeed; it is certain, and that he has got through his Italian campaigns. It is supposed that it will never be published during his lifetime. He rises early, takes a cup of coffee, breakfasts between twelve and one, à la fourchette, and dines about eight; he spends a great deal of time in his bath.

It is even said that Buonaparte issues decrees among his followers, and that one of these was that the Countess Bertrand should not see him for fourteen days. This I cannot believe.

From Dr. O’Meara we learned that it is Buonaparte’s wish to reside in Scotland, which he looks forward to when they begin to think less of his escape, which from this island he ridicules the idea of. Indeed it is asserted that one of the most rational conversations he has ever held with any person on the island was on this subject. His Memorial to the British Nation, which has been sent home, is said to be great trash; it is supposed to have been written by General Montholon. Of Dr. Warden’s book, Buonaparte says that he is only a secondary character, and the Doctor the principle; he says that three-fourths of it are lies, the other true, but that at every page he could not help exclaiming, ‘Voilà un fat!’ (‘There’s a blockhead!’) His opinions of the Chinese Embassy are said to be very good. He thinks Lord Amherst should have performed the Kotow, or ceremony of the Nine Prostrations; this opinion is said to have hurt Sir George Staunton, who was the means of its not being done.

Buonaparte’s victualling bill for the last twelve months is said to have been 12,000l. While we were at the island nine shillings apiece were paid for ducks at his table. His provisions, and, I believe, wine, are sent daily to Longwood; his staff and servants are always attended by a soldier. I saw the Maître d’Hôtel in town with a soldier close after him.

The foreign commissioners have never yet seen the ex-Emperor. They were all at the ball. Count Balmain, the Russian Commissioner, is a very handsome, genteel-looking man, and so is the Austrian; but the French, Count Montchenu, who has made Miss Betsy Balcombe’s name so famous in the ‘Courier,’ is, without any exception, one of the most complete figures of fun that can be imagined.

Buonaparte is now as little the subject of conversation at St. Helena as if he had long since ceased to exist. There are many inhabitants of the island who have never seen him; none of the offices of the 66th Regiment nor those of the flagship have ever seen him; nor has the Admiral himself, through six weeks at the island; nor has Lady Lowe ever been introduced to him.

Count Bertrand is styled Grand Marshal of the Palace. The parents of the Countess were Irish; she is said to be a relation of the present Lord Dillon. She speaks English very well and very prettily.

Poniatowsky, who is in England styled Count and Colonel, is allowed by everybody here to be a great blackguard and drunkard. Napoleon would not have anything to say to him, but that he might be styled Captain if it would do him any good. He is allowed by all parties to have been at the best a mere adventurer who expected to have made a good thing of coming to St. Helena; he was only a sous-lieutenant under Buonaparte. When ordered off the island, he wished to take leave of his master, who said he was busy and could not see him, but sent him a present of a few pieces of money.

Buonaparte one day observed a captain of the navy on his grounds looking at him; he immediately asked Bertrand who this was, and being told that he spoke French very well, and had been a prisoner in France, he thought it must be Captain Wallis of the Podargus, formerly first lieutenant with Captain Wright, who is supposed to have been murdered in the Temple. He instantly ordered that he should be sent off his grounds and never permitted to come there again. This, instead of being Captain Wallis, who was at the time forty miles to leeward of the island, proved to be Captain Shaw of the Termagant. Buonaparte complained to Sir Hudson, and said that Captain Wallis had insulted him ad interrupted his walks, and begged that in future no one should be allowed to enter his grounds without permission. His remark on the occasion of his fancying this to be Captain Wallis was, that these were the means that the English too of securing him, sending all those characters to guard him.

The island of St. Helena is 10 ½ miles long, 6 ¾ broad, and 23 miles in circumference. A small vessel is always cruising to windward, and also one to leeward, besides which guard boats row round the different parts of the island all night. A ship is also anchored off Lemon Valley, so that his escape from this rock of the ocean is quite impracticable and need be dreaded.