After Napoleon’s death on 5 May 1821, a secular cult began to grow around him, propagated by the testimonies of the men and women who had accompanied him to St Helena. At the same time iconography in which Napoleon was compared to the mythological Prometheus became popular. The Napoleonic cult peaked at the time of the return of Napoleon’s mortal remains in December 1840. After 20 years of repeated requests by the relatives of the Emperor, King Louis-Philippe, encouraged by Adolphe Thiers, asked the British for permission to repatriate Napoleon’s body from St. Helena in order to bury him in France, in Paris. On 7 July 1840, Belle Poule and Favorite left Toulon harbour with several of Napoleon’s former companions in exile on board: Empire generals Bertrand and Gourgaud, the valet Marchand, the second footman and librarian St Denis, (also known as Ali Mamluk), and Emmanuel de Las Cases, the son of Napoleon’s secretary, author of the Memorial of St Helena. On St Helena, Napoleon’s body was exhumed 15 October, 25 years to the day after the arrival of Northumberland in Jamestown. On 15 December, a procession of nearly a million people accompanied the Emperor’s remains to the Invalides, where his body was initially laid to rest in the Chapelle Saint Jérôme awaiting the completion of a specially built crypt where his body was finally laid to rest in 1861 in the imperial tomb designed by Louis Tullius Visconti. In April 1821, the Emperor had expressed in his will his wish to be buried “on the banks of the Seine, among the French people that I loved so much”.

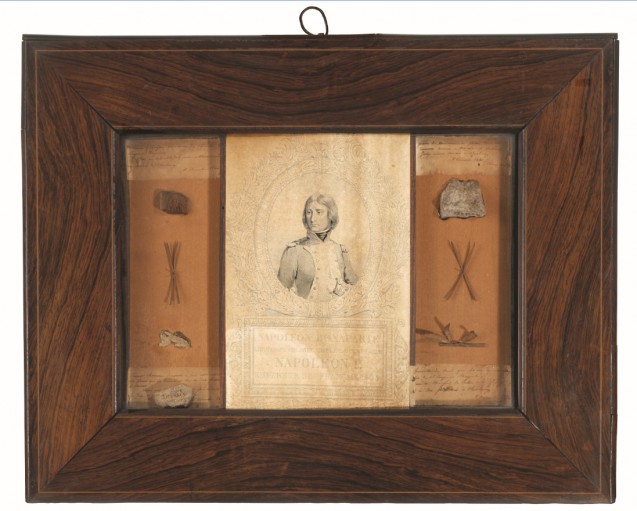

The pilgrims of the 1840 voyage and Napoleon’s companions made a point of bringing back various souvenirs of St Helena in memory of his exhumation, and in particularly of Geranium Valley where the Emperor’s body had been buried: principally plants, stones, pieces of the sarcophagus, or indeed water samples from the source from which the Emperor drank. When placed in a frame, these ordinary objects took on an almost sacred dimension.

This group of relics was collected by Louis Marchand, the Emperor’s head valet. Marchand had been chosen by Bertrand to replace Louis Constant Wairy, who fled after the first abdication at Fontainebleau. He followed Napoleon into exile, on both occasions: to Elba and to St Helena. Referred to as a “friend” by the Emperor in his will, he would be one of the will’s three executors.

Four elements in this reliquary frame were collected from the Geranium Valley: two pieces of masonry (a fragment of Roman cement that had entirely covered the slab which closed the vault, and a piece of masonry from the side wall that adjoined the tomb and had to be partially demolished in order to extract the Emperor’s coffin), a piece of branch from the only remaining willow tree of those that had shaded the tomb of Napoleon in 1821, and a piece of the mahogany coffin, the fourth and last of those in which the Emperor had been laid to rest in 1821. Rendered useless by the presence of two new coffins from France, it was to remain on St Helena but every member of the travelling party of the ‘Return of the Ashes’ (as his mortal remains were referred to – his body was not cremated) received a piece of it. These four relics are accompanied by handwritten notes by Marchand, attesting to their origin. In the composition of the reliquary frame, they are arranged around a print entitled “Napoleon Bonaparte Lieutenant Colonel, 1er B[ataill]on de la Corse en 1792 / Napoléon Ier Empereur des Français 1804”. It was published in 1840 after a design by Leopold Massard and engraved by Claude Dien, and was inspired by a 1834 painting by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, now in the collection of the Château de Versailles.

Upon their return to France in late November 1840, Louis Marchand and the other expedition members stayed in the harbour of Cherbourg until 8 December, when Napoleon’s mortal remains were transferred to the steamship La Normandie to be taken to the port of Le Havre whence they began their final journey along the river Seine to Paris. On 5 December, Louis Marchand gave the relics of St Helena to Colonel Joly. This may have been Alfred Jean Louis Joly, who had served the Emperor in the battle of Dresden, Leipzig and Waterloo, and was promoted to colonel in 1833. It was probably he who decided to make the composition within the reliquary frame. Colonel Joly and his family must have treasured the relics which are still presented in their original frame.

It was during the “Imperial Cruise” aboard the ocean liner France, organized in the spring of 1969 for the bicentenary of the birth of Napoleon, that the entrepreneur and collector Martial Lapeyre acquired the reliquary. This trip made several stopovers on Corsica, Elba, but also on the island of St Helena. During the return journey, on 23 April an auction took place simultaneously on board the ship and in Paris. Among the presented lots, Martial Lapeyre acquired lot number 98, described as “important relics of St Helena, collected by and given by Marchand.” They entered the collection of the Fondation Napoléon in 1987.

Elodie Lefort, October 2015 (English translation Rebecca Young)