A centenary in the shadow of the First World War

The scale of the commemorations surrounding the centenary of Napoleon’s death can only be understood in the context in which those commemorations took place.

France was emerging from the most deadly conflict it had ever experienced. And the ceremonies planned, including a gala and an international conference, constituted a political first: this was the first ever national tribute paid to Napoleon under the Republican regime. The Return of the Napoleon’s Mortal Remains , in 1840 during the reign of Louis-Philippe, and, to a lesser extent, the centenary of Napoleon’s birth, in 1869, during that of his nephew Napoleon III, were the only other two explicit national tributes to the exile of St Helena. There had also been no shortage of local or spontaneous initiatives, particularly by groups of veterans of the wars of the 19th century, especially after the War of 1870, but the centenary of Napoleon’s death took on a dimension of its own in the post-war period of 1918.

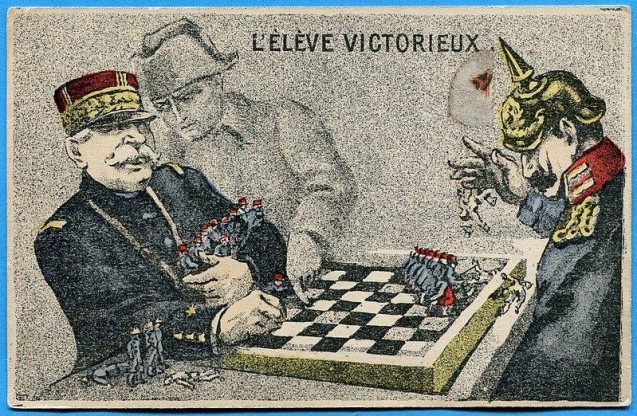

During the First World War, the figure of Napoleon, a victorious warlord in Europe, particularly against the Prussians, was used by the press to galvanise French troops and civilians alike and to fire their imagination.

After the costly victory (in terms of human losses) of the Triple Entente (France, Russian Empire, and British Empire) in 1918, post-war France, even in its Republican manifestation, sought to commemorate a great figure in its history, to erase the memory of the defeat against Prussia and its allies in the war of 1870 and to affirm its solidity on a European scale by commemorating the centenary of Napoleon’s death with great pomp. Nor would the population be outdone in participating in this commemoration in May 1921.

Preparing for the Centenary of Napoleon’s death: the Centenary Committee

Alexandre Millerand, President of the French Republic from 1920 to 1924

A committee, in the form of a general assembly with two hundred members, was convened on 27th November 1920 in order to prepare the ceremonies of 5th May 1921 and placed under the august patronage of the President of the Republic, Alexandre Millerand. From the start, the committee was placed under the honorary presidency of Marshal Foch and Édouard Driault, founder of the Revue des études napoléoniennes in 1912. The latter, with Patrice Contamine de Latour, was the main organiser of the events. After reaffirming the apolitical character of these commemorations, where civilians, military associations and members of the clergy should be represented, the committee decided on an extensive programme including publications, conferences, exhibitions (notably in Compiègne, Versailles and Malmaison). An international dimension to this commemoration was planned: museums in Waterloo and Austria were to be approached, and a trip to Saint Helena was also envisaged. A historical congress was also to be held at the Sorbonne.

Several of the ideas put forward at the meetings of the Centenary Committee however never saw the light of day: a parade at the Vendôme column was abandoned, as was the idea of a banquet. After a discreet start, this preparatory work eventually made its way into the French and then international press, once the Presidents of the Republic and the Council had confirmed their participation in the event.

The centenary commemorations

Before 5 May, two preliminary commemoratives events organised in the Emperor’s honour.

On 28 April 1921, the film L’agonie des Aigles, based on the successful novel Les demi-solde by Georges d’Esparbès, directed by Dominique Bernard-Deschamps, was given a gala performance at the Trocadero, in aid of post-war aid associations. The magazine Comœdia noted: “the most solemn moment of the evening, that when enthusiasm was at its peak, was when Marshal Foch entered the room. The film was interrupted, Alexandre George’s music was momentarily replaced by La Marseillaise. Frantic applause broke out on all sides of the room. Standing in front of the marshal’s box, the spectators, whose excitement had perhaps been screwed to fever pitch by the glorious epic presented to them on the screen, cheered frantically…(1 Link in French)”

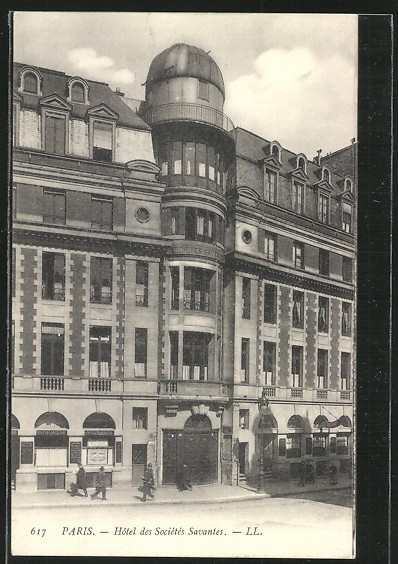

From 30 April to 3 May 1921, a history conference was held at the Hôtel des Sociétés Savantes (now the Maison de la Recherche, an annex of the Sorbonne University): there were four sessions covering the following subjects, namely, the Civil Code, public finance, public education, public works and the fine arts during the Consulate and the Empire. The aim of this conference was to study the institutional aspect of Napoleon’s reign in order to draw out the main principles and apply them to the contemporary world. The conference, the audience for which included the great and the good of the political world of the time, was considered by the press to be fascinating but difficult, and it concluded with the following recommendations: that the legal codes of European countries should be unified under the aegis of the League of Nations; that the school curricula in France and in Europe on the Napoleonic period should be revised; that one of the most beautiful avenues in Paris should be named after Napoleon; and that more tangible bilateral links between France and Poland should be reestablished, in memory of the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw by the French Emperor. None of these recommendations was ever to see the light of day.

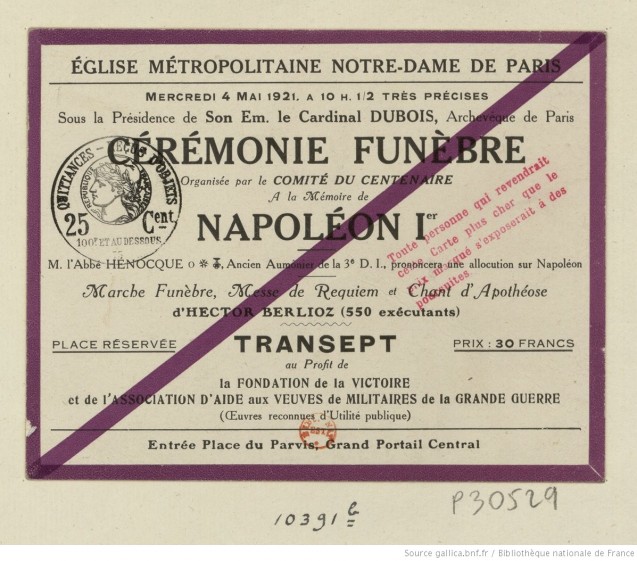

On 4 May 1921, a “Funeral Ceremony” was held in Notre-Dame de Paris, beginning at 10h30am, in memory of Napoleon and again for the benefit of war charities. As the feast of the Ascension and the solemnities for Joan of Arc were the 5th, the ceremony was brought forward to the day before, which did not prevent crowds from gathering in front of the church building from 8am, according to the newspapers. A mass was also celebrated beforehand at 10am. However, the diocesan and Catholic press gave little coverage to the event: the relationship between the Church and the Republic, but also between the Church and the instigator of the Concordat, was not without its problems in 1921. The Cathedral was nevertheless decked out with two tricolour flags and political figures flocked to the funeral service: General Lasson, head of President Millerand’s military household, led a procession of deputies, senators, state councillors and even judges who came to pay their respects to the Emperor. Although Marshal Foch was detained in London for a conference, the memory of the recent victory of 1918 was well represented: a group of young Alsatian women in traditional dress attended the service to represent the territories lost in 1870 and taken back from Germany after World War One.

The “Funeral Ceremony” was presided over by the Cardinal Archbishop of Paris, Monseigneur Dubois, and began at 10.30am and included music by Hector Berlioz for Napoleon, notably his Funeral march, his Requiem mass, and his Chant d’apothéose. The highlight of the “Funeral Ceremony” seems to have been the intervention of Abbé Georges Hénocques, a former military chaplain and hero of the recent war, who stood in the pulpit in his cassock and decorated with his Légion d’Honneur to affirm the links between Catholic patriotism and the heritage of Napoleon.

Also on 4 May, a solemn session was held at the Sorbonne at 3pm in honour of the civil institutions created by Napoleon. Chaired by the Minister of Public Works, Yves le Trocquer, it featured speeches by Édouard Driault, President of the Centenary Committee, and Georges Lacour-Gayet, historian and member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et politiques, before the Minister’s concluding reply. A specialist in Talleyrand, Georges Lacour-Gayet made his mark by successively praising the Concordat, the Legion d’Honneur, the Civil Code and the University, all of which were inherited from Napoleon.

Once these two tributes to Napoleon, religious and civil, had taken place, the 5th of May was to be devoted to those of the Army and the Republic.

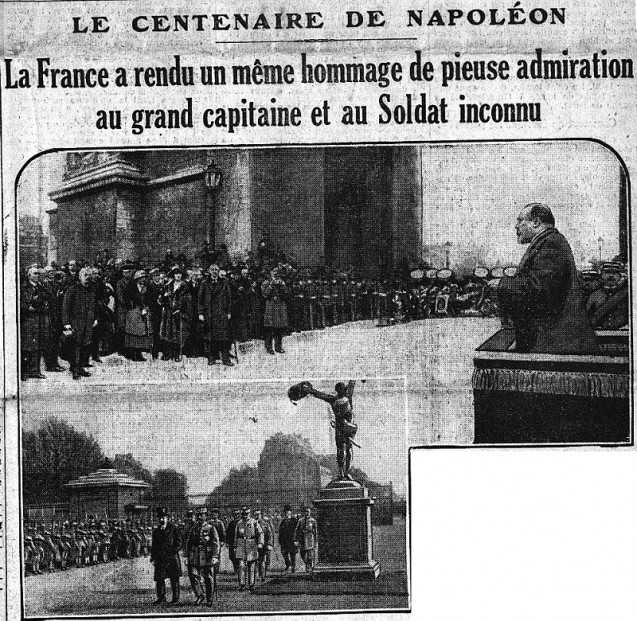

The commemorations began on 5 May at 10am with a tribute from the French army at the Arc de Triomphe. Combining homage to the soldiers of the Grande Armée and the soldiers of the Great War, this ceremony took place in the presence of Marshals Foch, Pétain and Fayolle, as well as a number of generals who had distinguished themselves in the recent conflict: Weygand, Pau, Buat, etc. They were once again accompanied by young Alsatian women in traditional costumes, this time bearing the names of the famous generals of the army of the Rhine: Lasalle, Lefebvre, Kellerman, Kléber, Ney, Rapp and Mouton. The crowd was held back by lines of municipal guards when at 10.30 am the car of President Millerand, escorted by the cavalry of the Republican Guard, drove into the Place de l’Étoile. The Minister of War, Louis Barthou, followed him; he saluted the tomb of the Unknown Soldier and took his place in front of the official gallery where Barthou gave his speech.

After the speech by the Minister for War, which received a long standing ovation, the President again saluted the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and attended the military parade up the Avenue de la Grande Armée which was inaugurated by General Trouchaud, Deputy Military Governor of Paris. After this parade and another salute to the Tomb, the President got back into his car, still escorted, and drove down the Champs-Élysées while the associations of veterans of the war of 1870 and other veterans’ associations – including the American Legion – followed, each delegation placing a wreath of flowers at the foot of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The parade was closed by delegations of Cossacks and White Russians. Some 500 to 600 members of associations paid tribute to the Emperor and the country.

The afternoon of the 5th May saw the tribute to the Emperor continue at the Hôtel National des Invalides. Shortly before 5 pm, under a sun that the press would not fail to note, an honour guard of soldiers lined the vestibule of the Dome chapel; the crowd had been waiting for several hours. Two veterans carried a cushion on which rested the sword Napoleon had carried at Austerlitz. In the courtyard in front of the Dome were stationed detachments of the 6th, 7th and 10th infantry divisions, the band of the 104th, and the flag of the 5th line infantry; in Place Vauban, the Republican Guard, two artillery batteries and two cavalry squadrons awaited the arrival of the representative of President Millerand, Minister Barthou, and the President of the Council. At 5pm precisely, after the command “present arms”, Marshal Foch made his entrance, followed by Marshals Fayolle and Pétain, then Monseigneur Dubois. Gabriel Fauré’s Chant funébre, specially composed for the centenary, was then played, while Cardinal Dubois pronounced a Pater Noster, signed the Emperor’s tomb, and made an adjuration in the name of the Most High, before incensing eight times the place where Napoleon’s remains were laid to rest in the crypt and intoning a Libera Me.

Marshal Foch then took up the sword of Austerlitz, faced the tomb and gave the speech that was to remain the most famous moment of the centenary of the Emperor’s death. The ceremony ended at 5.49pm, the precise time of Napoleon’s death on St Helena one hundred years earlier.

► Read Maréchal Foch’s speech over the tomb of Napoleon 5 May 1921 (in French © Gallica/Bnf)

Reception of the centenary of Napoleon’s death in the French press

From 5 to 6 May 1921, the French press of all political persuasions reported on the religious, civil and military ceremonies relating to the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death. Since it was an event of a highly political nature, despite the preoccupations of the organising committee that it should be neutral, the centenary was immediately interpreted according to the majority and minority tendencies of the French press chessboard.

Although the press as a whole (Le Matin, Le Petit Journal, Le Petit Parisien, Le Radical, La Croix, L’Action française, etc.) gave a rather serious account of the two days of 4 and 5 May 1921, none of the newspapers failed to emphasise the explicitly desired rapprochement between the soldiers of the Grande Armée and those went to front in 1914, or even the rapprochement between the symbols of the Eagle and the Fleur de Lys during the mass.

Nevertheless, of note are the emotional headlines in the Republican newspaper Le Matin dated 5 and 6 May 1921: “Napoleon’s centenary, the radiance of a glory” and “Napoleon’s centenary, France paid equal homage of pious admiration to the great captain and to the unknown soldier”. As oppposed to the left leaning L’Humanité and Le Populaire, opposition newspapers marked by post-war pacifism, on the same dates: in the former, Marcel Gachin proclaimed: “I have only ever vowed hatred to one being… Damn you, Napoleon! “while Le Populaire hammered it home: “Of all the vain boasts of nationalism, there is none more likely to do France a disservice in the world than the celebration of the centenary of Napoleon’s death”.

One hundred years after his death, Napoleon unleashed passions, as he does today at the time of the bicentenary of his death…

Marie de Bruchard, with Alexis Halpérin – huge thanks to him!

April 2021

(translation PH)

![[2021 Année Napoléon] 5 May 1921, the centenary of Napoleon’s death](https://www.napoleon.org/wp-content/thumbnails/uploads/2021/05/5-mai-1921-centenaire-de-la-mort-de-napoleon-ceremonie-sous-larc-de-triomphe-tt-width-637-height-356-crop-1-bgcolor-ffffff-lazyload-0.png)